My @FreshRSS installation is the first, last, and sometimes only place I go on the Internet. When a site doesn’t have a feed but I wish it did, I add one using middleware (e.g. danq.me/far-side-rss).

Here’s to the next 20 years of my #RSS addiction.

My @FreshRSS installation is the first, last, and sometimes only place I go on the Internet. When a site doesn’t have a feed but I wish it did, I add one using middleware (e.g. danq.me/far-side-rss).

Here’s to the next 20 years of my #RSS addiction.

This checkin to GC944X7 Pop! Bang! Crack! Goes the Christmas Cracker reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

The second of the caches in this series that I found in between errands, this afternoon, was probably the easiest, because the hiding place reminds me distinctly of one of my own hides! This one, though, enjoys some excellent Christmas theming, for which a FP is due. TFTC!

This checkin to GC93YF2 O Christmas Tree reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

I’d picked this one out as an essential for this afternoon’s “between jobs” hunt, because it completes my Solar System Wonders set. How pleased I was to find that through this cache a tree is properly – albeit sparsely – decorated. Thanks for this, my third and final cache of the day. I’ll be back to finish the series next time I’m around here with time to spare, I’m sure!

This checkin to GC93W4C Twelve Days of Caching reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Having “solved” all the puzzles some time ago I’m picking away at finding the caches in this series a few at a time, starting the other week, every time I happen to be passing nearby. I felt a little overlooked by nearby windows this drizzly afternoon but I needn’t have engaged my stealth skills: the coordinates were spot on and I soon had the cache in my hand. TFTC.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

In his latest video, Andrew provides a highly-accessible and slick explanation of all of the arguments against what3words that I’ve been making for years, plus a couple more besides.

Arguments that he makes that closely parallel my own include that what3words addresses are (a) often semantically-ambiguous, (b) potentially offensive, (c) untranslatable (and their English words, used by non-English speakers, exaggerates problem (a)), and (d) based on an aggressively-guarded proprietary algorithm. We’re of the same mind, there. I’ll absolutely be using this video to concisely explain my stance in future.

Andrew goes on to point out two further faults with the system, which don’t often appear among my arguments against it:

The first is that its lack of a vertical component and of a mechanism for narrowing-down location more-specifically makes it unsuitable for one of its stated purposes of improving addressing in parts of the developing world. While I do agree that what3words is a bad choice for use as this kind of addressing system, my reasoning is different, and I don’t entirely agree with his. I don’t believe that what3words are actually arguing that their system should be used alone to address a letter. Even in those cases where a given 3m × 3m square can be used to point to a single building’s entryway, a single building rarely contains one person! At a minimum, a “what3words”-powered postal address is likely to specify the name of the addressee who’s expected to be found there. It also may require additional data impossible to encode in any standardisable format, and adding a vertical component doesn’t solve this either: e.g. care-of addresses, numbered letterboxes, unconventional floor numbers (e.g. in tunnels or skybridges), door colours, or even maps drawn from memory onto envelopes have been used in addressed mail in some parts of the world and at some times. I’m not sure it’s fair to claim that what3words fails here because every other attempt at a universal system would too.

Similarly, I don’t think it’s necessarily relevant for him to make his observation that geological movements result in impermanence in what3words addresses. Not only is this a limitation of global positioning in general, it’s also a fundamentally unsolvable problem: any addressable “thing” is capable or movement both with and independent of the part of the Earth to which it’s considered attached. If a building is extended in one direction and the other end demolished, or remodelling moves its front door, or a shipwreck is split into two by erosion against the seafloor, or two office buildings become joined by a central new lobby between them, these all result in changes to the positional “address” of that thing! Even systems designed specifically to improve the addressability of these kinds of items fail us: e.g. conventional postal addresses change as streets are renamed, properties renamed or renumbered, or the boundaries of settlements and postcode areas shift. So again: while changes to the world underlying an addressing model are a problem… they’re not a problem unique to what3words, nor one that they claim to solve.

One of what3words’ claimed strengths is that it’s unambiguous because sequential geographic areas do not use sequential words, so ///happy.adults.hand is nowhere near

///happy.adults.face. That kind of feature is theoretically great for rescue operations because it means that you’re likely to spot if I’m giving you a location that’s in

completely the wrong country, whereas the difference between 51.385, -1.6745 and 51.335, -1.6745, which could easily result from a transcription error, are an awkward 4 miles away. Unfortunately, as Andrew

demonstrates, what3words introduces a different kind of ambiguity instead, so it doesn’t really do a great job of solving the problem.

And sequential or at least localised areas are actually good for some things, such as e.g. addressing mail! If I’ve just delivered mail to 123 East Street and my next stop is 256 East Street then (depending on a variety of factors) I probably know which direction to go in, approximately how far, and possibly even what side of the road it’ll be on!

That’s one of the reasons I’m far more of a fan of the Open Location Code, popularised by Google as Plus Codes. It’s got many great features, including variable resolution (you can give a short code, or just the beginning of a code, to specify a larger area, or increase the length of the code to specify any arbitrary level of two-dimensional precision), sequential locality (similar-looking codes are geographically-closer), and it’s based on an open standard so it’s at lower risk of abuse and exploitation and likely has greater longevity than what3words. That’s probably why it’s in use for addresses in Kolkata, India and rural Utah. Because they don’t use English-language words, Open Location Codes are dramatically more-accessible to people all over the world.

If you want to reduce ambiguity in Open Location Codes (to meet the needs of rescue services, for example), it’d be simple to extend the standard with a check digit. Open Location Codes use a base-20 alphabet selected to reduce written ambiguity (e.g. there’s no letter O nor number 0), so if you really wanted to add this feature you could just use a base-20 modification of the Luhn algorithm (now unencumbered by patents) to add a check digit, after a predetermined character at the end of the code (e.g. a slash). Check digits are a well-established way to ensure that an identifier was correctly received e.g. over a bad telephone connection, which is exactly why we use them for things like credit card numbers already.

Basically: anything but what3words would be great.

This checkin to GC6H7HD Zoology reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Having succeeded at my primary goal for the evening of finding the challenging sibling of this cache, Herbology, I realised I probably had just enough time left before sunset to find this one, too, if I got a move on. As I ran along the path and rounded the corner to the field at the edge of which this cache is found, though, I was in for a bit of a surprise!

I’ve joked to my partner that the deer in South Leigh seem to be suicidal, based on the frequency with which they will leap out in front of my car or bike on the rare occasions that I pass through the village (I’ve avoided hitting any so far, but they keep trying to make me). Well today it was my turn to narrowly avoid being run over, as a pair of large deer rushed out from the field and almost bowled me over! Perhaps now they’ll understand how startling it is to almost end up ploughing through a living thing and avoid jumping out in front of me? Or perhaps not.

In any case, I quickly found the cache’s hiding place once I’d crossed the field, and I could have probably done it 10 minutes later if I’d needed to… but probably not much beyond that; once the sun was gone my eyes wouldn’t have been up to it! As others have noted, this cache is in need of repair: I’m pretty sure it once must have fit the theme of its siblings but right now it’s a cracked, open shell, miraculously still dry enough inside to sign the log but that’s probably only a matter of time. :-(

Anyway: thanks to the CO for a fun series and a delightful, if frantic, walk some of these Autumn evenings. TFTCaches!

This checkin to GC6H7JG Herbology reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

I get precious little time for geocaching lately: between work, childcare, household and volunteering commitments it’s a challenge to squeeze in a quick expedition here and there. That’s doubly-true as the days get shorter: after finishing work, feeding the children etc. it’s already starting to get dim, and caches that I know will be more-challenging to find – like this D4.5! – become a race against time.

A fortunate side-effect of my unusual living arrangement is that I’m only needed for bathtime and bedtime story-reading duties two nights out of every three, and so when this evening achieved the hat-trick of me not being on bedtime duty, not being urgently needed for work in the evening, and the weather looking good, I leapt onto my bike to come and find this cache. I’d found its sibling Geology a fortnight ago without two much difficulty, but – knowing that Herbology would be much harder! – I’d planned to come out and perform a dedicated search for this and this cache only this evening. I cycled to South Leigh and then up the old Barnard Gate road, stopping at N 51° 46.366, W 001° 25.259′ to lock my bike to a wooden footbridge at the point at which a footpath crosses the road. From there, I jogged North up the path to find the GZ (bringing my front bike light for use as a torch, should the need arise).

I had anticipated that a search would be needed and had a few ideas about the kinds of things I might be looking for, but when after approaching half an hour I’d found nothing at all and had resorted to poking at candidate hiding places with a stick while I shone my torch around, I was worried that this expedition might be a bust. Swallowing my pride, I messaged the CO to see if they might be able to provide a further hint. Amazingly, they were not only online but able to give a hint that pointed me at exactly the kind of thing I ought to be hunting for… because it turned out I’d already moved the cache container while hunting elsewhere in its hiding place!

Upon returning this expertly-stealthy cache to its hiding place, I realised that I might just have time to find the third of this triplet, and so I took off at top speed for Zoology.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…I am not saying Apple’s approach is wrong. What Apple is doing is important too, and I applaud the work Apple has been doing in improving privacy on the web.

But it can’t be the only priority. Just imagine what the web would look like if every browser would have taken that approach 20 years ago.

Actually, no, don’t imagine it all. Just think back at Internet Explorer 6; that is what the web looked like 20 years ago.

…

There can only be one proper solution: Apple needs to open up their App Store to browsers with other rendering engines. Scrap rule 2.5.6 and allow other browsers on iOS and let them genuinely compete.

As a reminder, Safari is the only web browser on iOS. You might have been fooled to think otherwise by the appearance of other browsers in the App Store or perhaps by last year’s update that made it possible at long last to change the default browser, but it’s all an illusion. Beneath the mask, all browsers on iOS are powered by Safari’s WebKit, or else they’re booted from the App Store.

Neils’ comparison to Internet Explorer 6 is a good one, but as I’ve long pointed out, there’s a big and important difference between Microsoft’s story during the First Browser War and Apple’s today:

Apple are holding the Web back… and getting away with it.

This checkin to GC6FD6N Cumnor Minions - Norbert reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

A quick almost-CnD on the school run. I’d love to come back and do the series someday! Found easily (although the hint object is nowhere in sight!), but container was challenging to open! Luckily the edge of the carabiner I use to clip my GPSr to my belt was up to the task! TFTC.

This checkin to GC93T66 Mistletoe and Wine reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

“Solved” all the puzzles some time ago, then came out to find this cache as a drive-by (on the minor, not the major, nearby road, of course!) while in-between other errands nearby. Was looking for something smaller when I laid my hands on the cache container, which I thought looked “out of place”, but the weight balance of the thing I’d picked up felt wrong… like something was loose inside? That’s when I realised I was holding the cache! Signed log and returned it to its spot. TFTC.

When do I #blog? A breakdown of my top four #indieweb content types – articles, reposts, checkins and notes – by month.

Unsurprisingly my checkins, which represent #geocaching/#geohashing activity, grow in the spring and peak in the summer when the weather’s better!

At first I assumed the notes peak in November might have been thrown off by a single conference, e.g. musetech, but it turns out I’ve just done more note-friendly things in Novembers, like Challenge Robin II and my Cape Town meetup, which are enough to throw the numbers off.

Sometimes a web standard disappears quickly at the whim of some company, perhaps to a great deal of complaint (and at least one joke).

But sometimes, they disappear slowly, like this kind of web address:

http://username:password@example.com/somewhere

If you’ve not seen a URL like that before, that’s fine, because the answer to the question “Can I still use HTTP Basic Auth in URLs?” is, I’m afraid: no, you probably can’t.

But by way of a history lesson, let’s go back and look at what these URLs were, why they died out, and how web browsers handle them today. Thanks to Ruth who asked the original question that inspired this post.

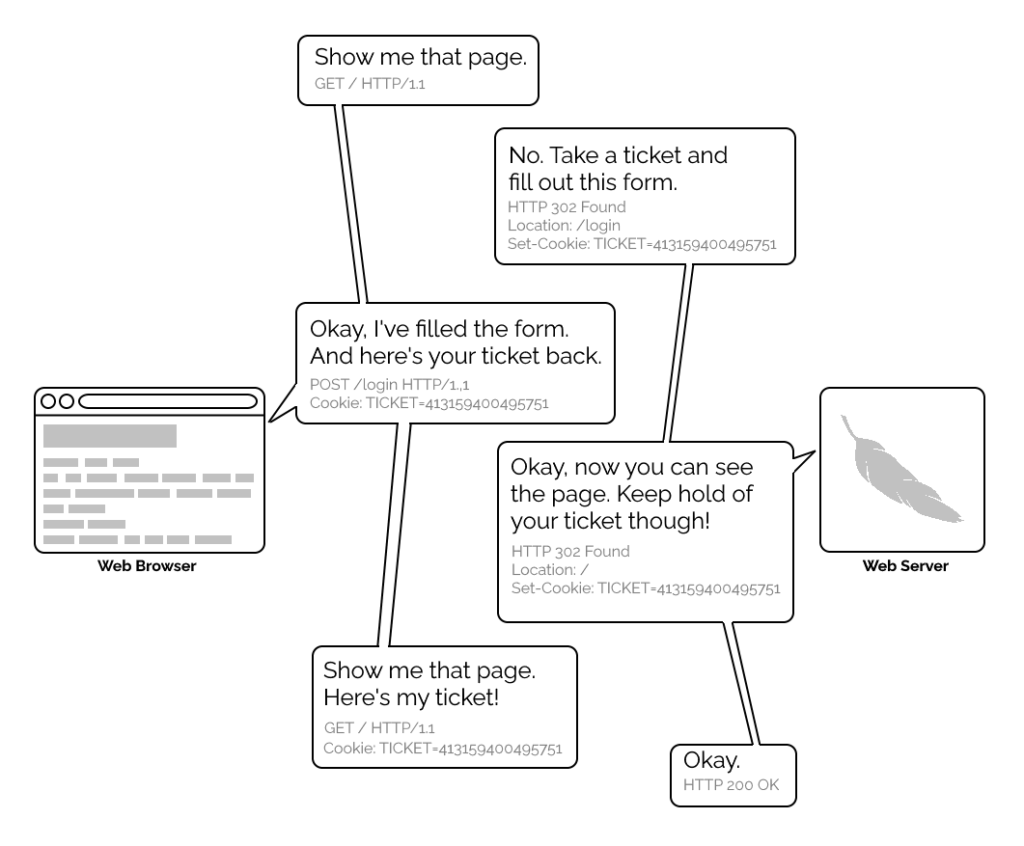

The early Web wasn’t built for authentication. A resource on the Web was theoretically accessible to all of humankind: if you didn’t want it in the public eye, you didn’t put it on the Web! A reliable method wouldn’t become available until the concept of state was provided by Netscape’s invention of HTTP cookies in 1994, and even that wouldn’t see widespread for several years, not least because implementing a CGI (or similar) program to perform authentication was a complex and computationally-expensive option for all but the biggest websites.

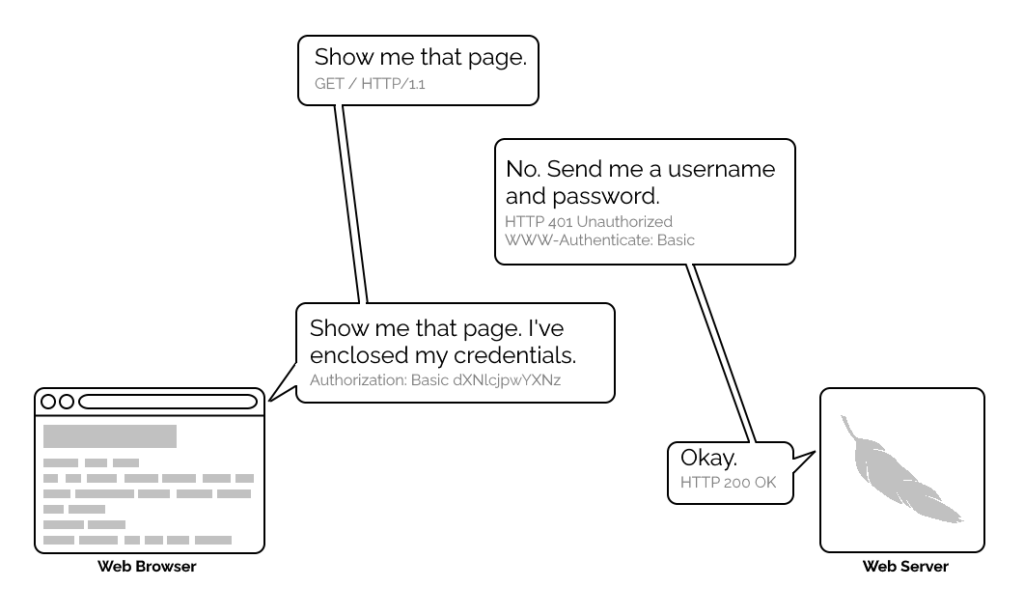

1996’s HTTP/1.0 specification tried to simplify things, though, with the introduction of the WWW-Authenticate header. The idea was that when a browser tried to access something that required

authentication, the server would send a 401 Unauthorized response along with a WWW-Authenticate header explaining how the browser could authenticate

itself. Then, the browser would send a fresh request, this time with an Authorization: header attached providing the required credentials. Initially, only “basic

authentication” was available, which basically involved sending a username and password in-the-clear unless SSL (HTTPS) was in use, but later, digest authentication and a host of others would appear.

Webserver software quickly added support for this new feature and as a result web authors who lacked the technical know-how (or permission from the server administrator) to implement

more-sophisticated authentication systems could quickly implement HTTP Basic Authentication, often simply by adding a .htaccess file to the relevant directory.

.htaccess files would later go on to serve many other purposes, but their original and perhaps best-known purpose – and the one that gives them their name – was access

control.

A separate specification, not specific to the Web (but one of Tim Berners-Lee’s most important contributions to it), described the general structure of URLs as follows:

<scheme>://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>/<url-path>#<fragment>

At the time that specification was written, the Web didn’t have a mechanism for passing usernames and passwords: this general case was intended only to apply to protocols that did have these credentials. An example is given in the specification, and clarified with “An optional user name. Some schemes (e.g., ftp) allow the specification of a user name.”

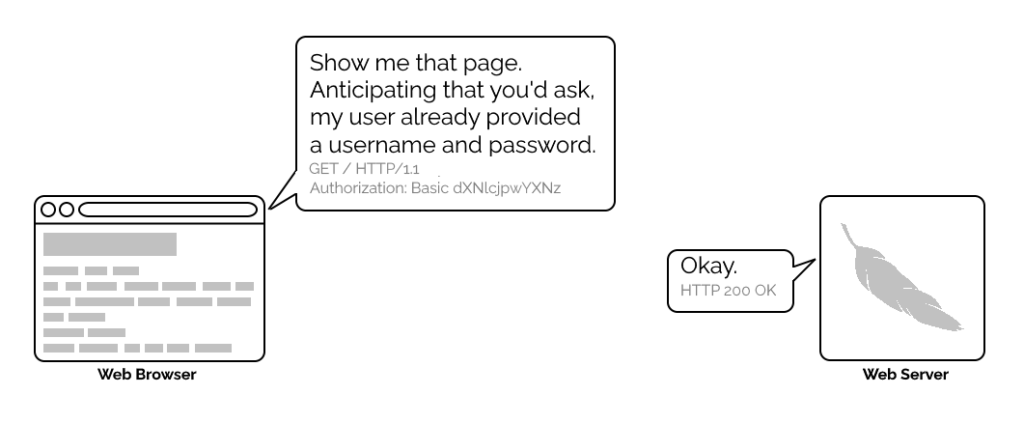

But once web browsers had WWW-Authenticate, virtually all of them added support for including the username and password in the web address too. This allowed for

e.g. hyperlinks with credentials embedded in them, which made for very convenient bookmarks, or partial credentials (e.g. just the username) to be included in a link, with the

user being prompted for the password on arrival at the destination. So far, so good.

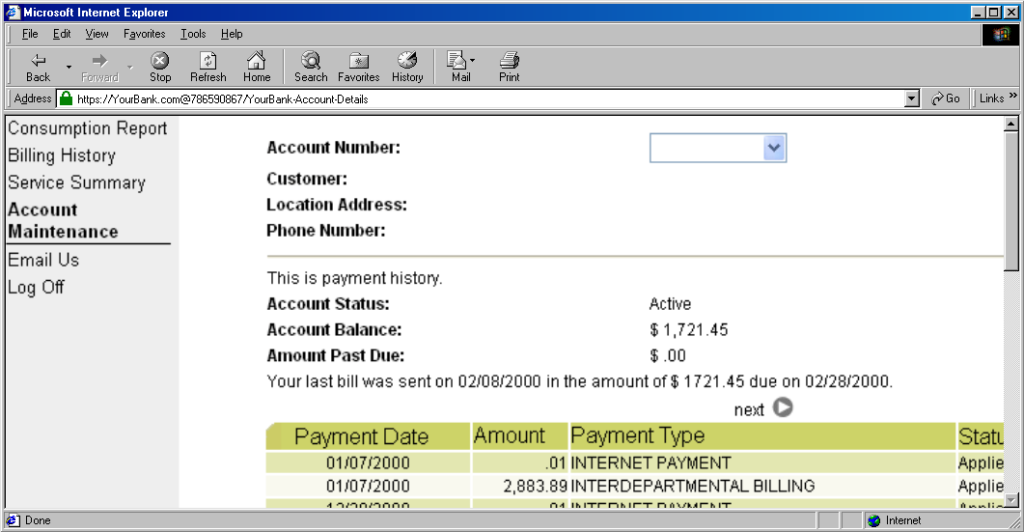

The technique fell out of favour as soon as it started being used for nefarious purposes. It didn’t take long for scammers to realise that they could create links like this:

https://YourBank.com@HackersSite.com/

Everything we were teaching users about checking for “https://” followed by the domain name of their bank… was undermined by this user interface choice. The poor victim would actually be connecting to e.g. HackersSite.com, but a quick glance at their address bar would leave them convinced that they were talking to YourBank.com!

Theoretically: widespread adoption of EV certificates coupled with sensible user interface choices (that were never made) could have solved this problem, but a far simpler solution was just to not show usernames in the address bar. Web developers were by now far more excited about forms and cookies for authentication anyway, so browsers started curtailing the “credentials in addresses” feature.

(There are other reasons this particular implementation of HTTP Basic Authentication was less-than-ideal, but this reason is the big one that explains why things had to change.)

One by one, browsers made the change. But here’s the interesting bit: the browsers didn’t always make the change in the same way.

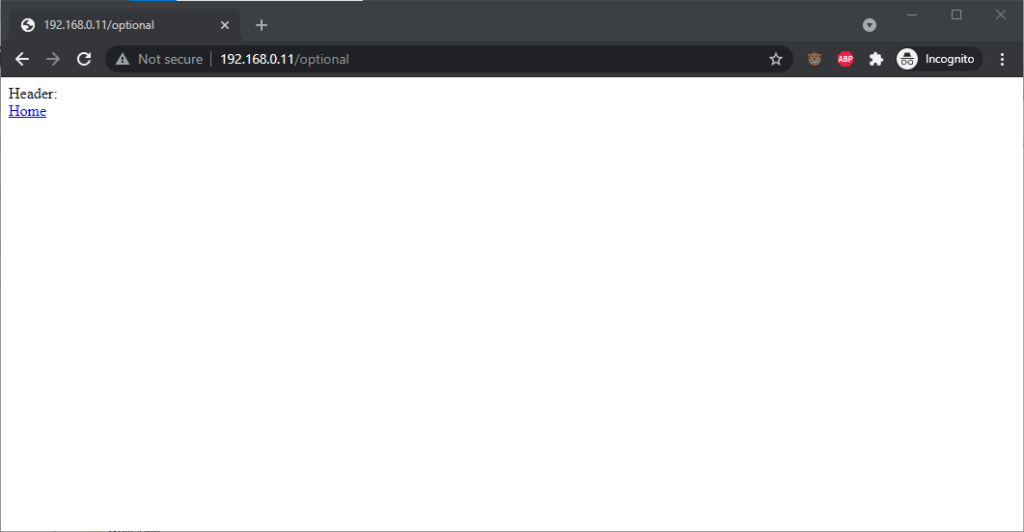

Let’s examine some popular browsers. To run these tests I threw together a tiny web application that outputs

the Authorization: header passed to it, if present, and can optionally send a 401 Unauthorized response along with a WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm="Test Site" header in order to trigger basic authentication. Why both? So that I can test not only how browsers handle URLs containing credentials when an authentication request is received, but how they handle them when one is not. This is relevant because

some addresses – often API endpoints – have optional HTTP authentication, and it’s sometimes important for a user agent (albeit typically a library or command-line one) to pass credentials without

first being prompted.

In each case, I tried each of the following tests in a fresh browser instance:

http://<username>:<password>@<domain>/optional (authentication is optional).

http://<username>:<password>@<domain>/mandatory (authentication is mandatory).

/mandatory.

/optional.

I’m only testing over the http scheme, because I’ve no reason to believe that any of the browsers under test treat the https scheme differently.

Chrome 93 and

Edge 93 both immediately suppressed the username and password from the address bar, along with the “http://” as we’ve come to expect of them. Like the “http://”, though,

the plaintext username and password are still there. You can retrieve them by copy-pasting the entire address.

Chrome 93 and

Edge 93 both immediately suppressed the username and password from the address bar, along with the “http://” as we’ve come to expect of them. Like the “http://”, though,

the plaintext username and password are still there. You can retrieve them by copy-pasting the entire address.

Opera 78 similarly suppressed the username, password, and scheme, but didn’t retain the username and password in a way that could be copy-pasted out.

Authentication was passed only when landing on a “mandatory” page; never when landing on an “optional” page. Refreshing the page or re-entering the address with its credentials did not change this.

Navigating from the “optional” page to the “mandatory” page using only relative links retained the username and password and submitted it to the server when it became mandatory, even Opera which didn’t initially appear to retain the credentials at all.

Navigating from the “mandatory” to the “optional” page using only relative links, or even entering the “optional” page address with credentials after visiting the “mandatory” page, does not result in authentication being passed to the “optional” page. However, it’s interesting to note that once authentication has occurred on a mandatory page, pressing enter at the end of the address bar on the optional page, with credentials in the address bar (whether visible or hidden from the user) does result in the credentials being passed to the optional page! They continue to be passed on each subsequent load of the “optional” page until the browsing session is ended.

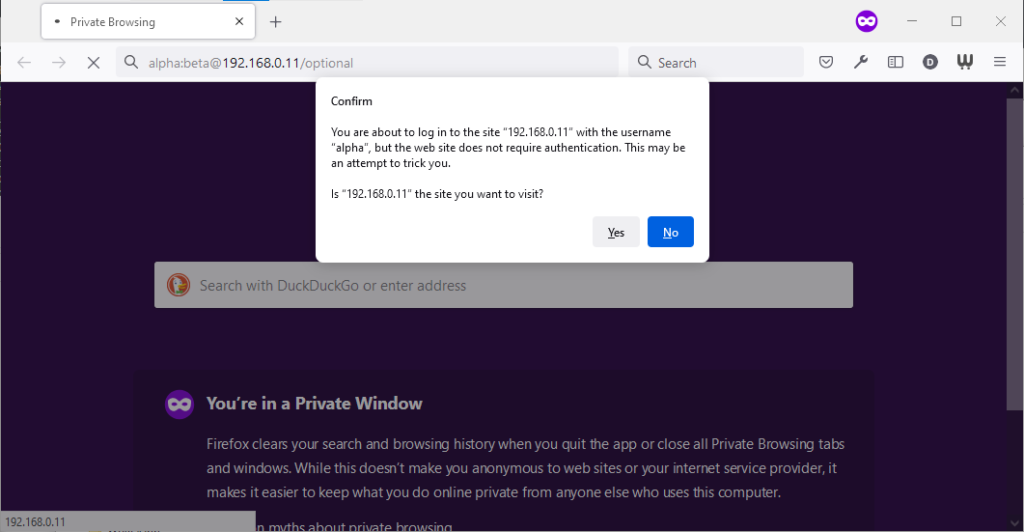

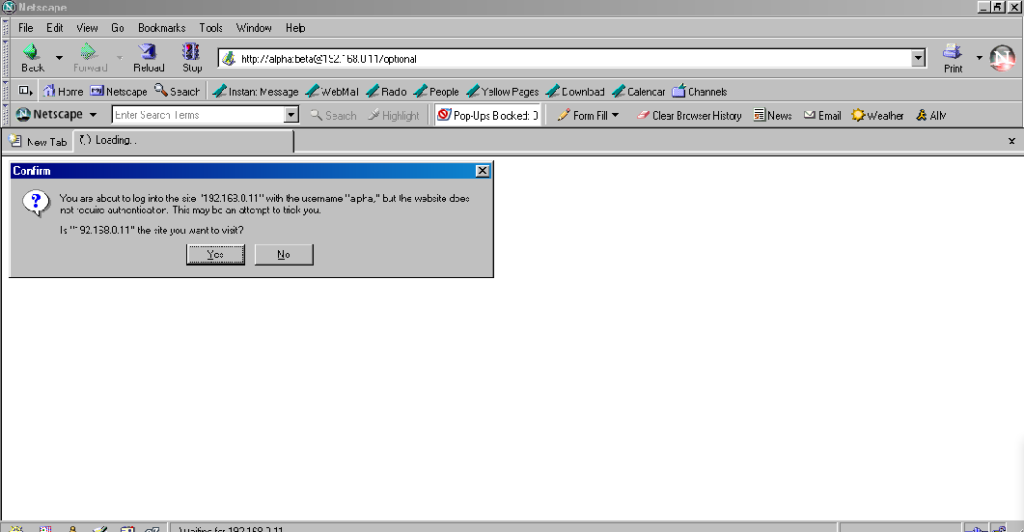

Firefox 91 does a clever thing very much in-line with its image as a browser that puts decision-making authority into the hands of its user. When going to

the “optional” page first it presents a dialog, warning the user that they’re going to a site that does not specifically request a username, but they’re providing one anyway. If the

user says that no, navigation ceases (the GET request for the page takes place the same either way; this happens before the dialog appears). Strangely: regardless of whether the user

selects yes or no, the credentials are not passed on the “optional” page. The credentials (although not the “http://”) appear in the address bar while the user makes their decision.

Firefox 91 does a clever thing very much in-line with its image as a browser that puts decision-making authority into the hands of its user. When going to

the “optional” page first it presents a dialog, warning the user that they’re going to a site that does not specifically request a username, but they’re providing one anyway. If the

user says that no, navigation ceases (the GET request for the page takes place the same either way; this happens before the dialog appears). Strangely: regardless of whether the user

selects yes or no, the credentials are not passed on the “optional” page. The credentials (although not the “http://”) appear in the address bar while the user makes their decision.

Similar to Opera, the credentials do not appear in the address bar thereafter, but they’re clearly still being stored: if the refresh button is pressed the dialog appears again. It does not appear if the user selects the address bar and presses enter.

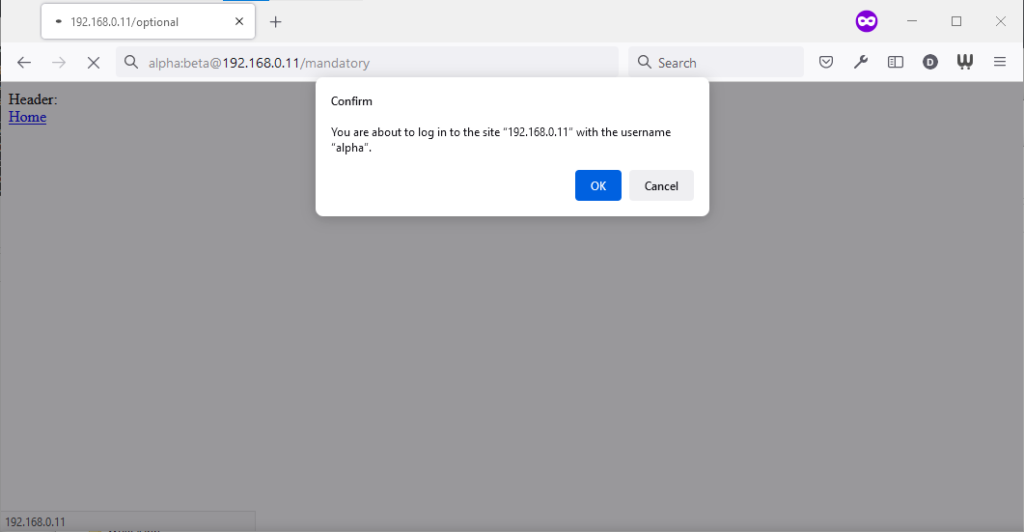

Similarly, going to the “mandatory” page in Firefox results in an informative dialog warning the user that credentials are being passed. I like this approach: not

only does it help protect the user from the use of authentication as a tracking technique (an old technique that I’ve not seen used in well over a decade, mind), it also helps the user

be sure that they’re logging in using the account they mean to, when following a link for that purpose. Again, clicking cancel stops navigation, although the initial request (with no

credentials) and the 401 response has already occurred.

Similarly, going to the “mandatory” page in Firefox results in an informative dialog warning the user that credentials are being passed. I like this approach: not

only does it help protect the user from the use of authentication as a tracking technique (an old technique that I’ve not seen used in well over a decade, mind), it also helps the user

be sure that they’re logging in using the account they mean to, when following a link for that purpose. Again, clicking cancel stops navigation, although the initial request (with no

credentials) and the 401 response has already occurred.

Visiting any page within the scope of the realm of the authentication after visiting the “mandatory” page results in credentials being sent, whether or not they’re included in the address. This is probably the most-true implementation to the expectations of the standard that I’ve found in a modern graphical browser.

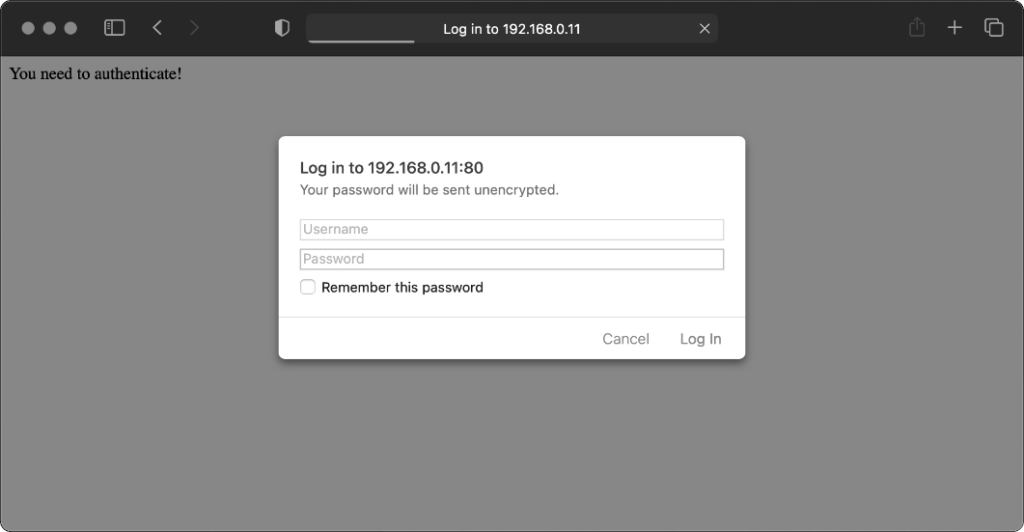

Safari 14 never displays or uses credentials provided via the web address, whether or not authentication is mandatory. Mandatory authentication is always met by a pop-up

dialog, even if credentials were provided in the address bar. Boo!

Safari 14 never displays or uses credentials provided via the web address, whether or not authentication is mandatory. Mandatory authentication is always met by a pop-up

dialog, even if credentials were provided in the address bar. Boo!

Once passed, credentials are later provided automatically to other addresses within the same realm (i.e. optional pages).

Let’s try some older browsers.

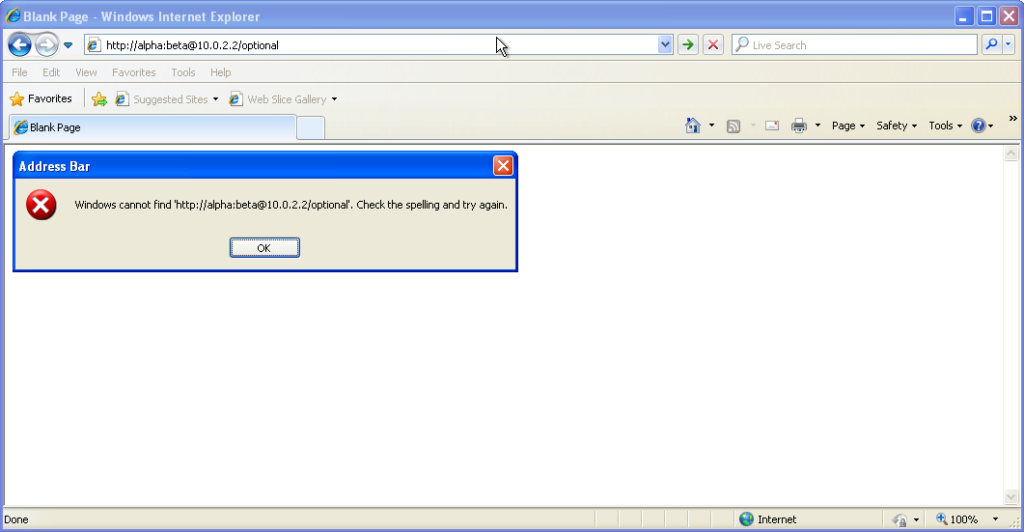

From version 7

onwards – right up to the final version 11 – Internet Explorer fails to even recognise addresses with authentication credentials in as legitimate web addresses, regardless of

whether or not authentication is requested by the server. It’s easy to assume that this is yet another missing feature in the browser we all love to hate, but it’s interesting to note

that credentials-in-addresses is permitted for

From version 7

onwards – right up to the final version 11 – Internet Explorer fails to even recognise addresses with authentication credentials in as legitimate web addresses, regardless of

whether or not authentication is requested by the server. It’s easy to assume that this is yet another missing feature in the browser we all love to hate, but it’s interesting to note

that credentials-in-addresses is permitted for ftp:// URLs…

…and

if you go back a little way, Internet Explorer 6 and below supported credentials in the address bar pretty much as you’d expect based on the standard. The error message seen in

IE7 and above is a deliberate design

decision, albeit a somewhat knee-jerk reaction to the security issues posed by the feature (compare to the more-careful approach of other browsers).

…and

if you go back a little way, Internet Explorer 6 and below supported credentials in the address bar pretty much as you’d expect based on the standard. The error message seen in

IE7 and above is a deliberate design

decision, albeit a somewhat knee-jerk reaction to the security issues posed by the feature (compare to the more-careful approach of other browsers).

These older versions of IE even (correctly) retain the credentials through relative hyperlinks, allowing them to be passed when they become mandatory. They’re not passed on optional pages unless a mandatory page within the same realm has already been encountered.

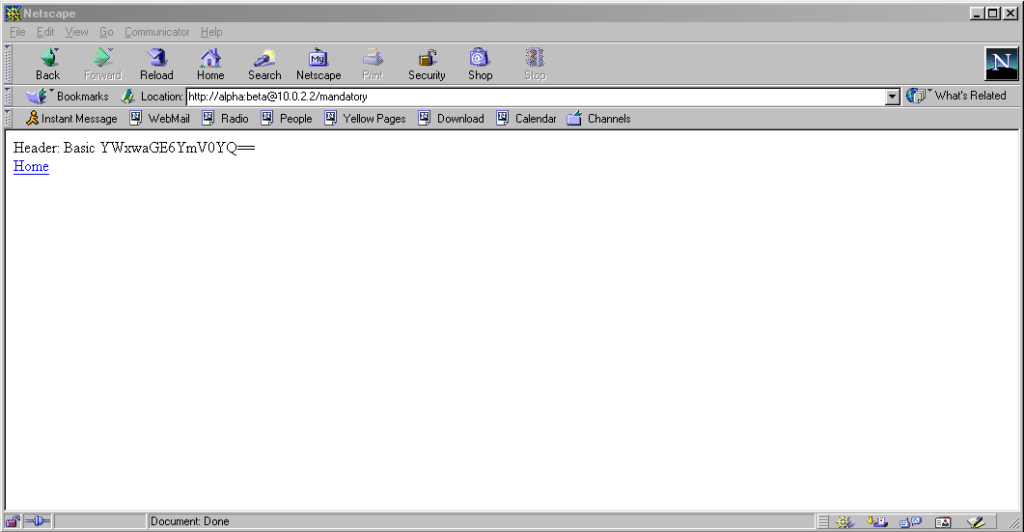

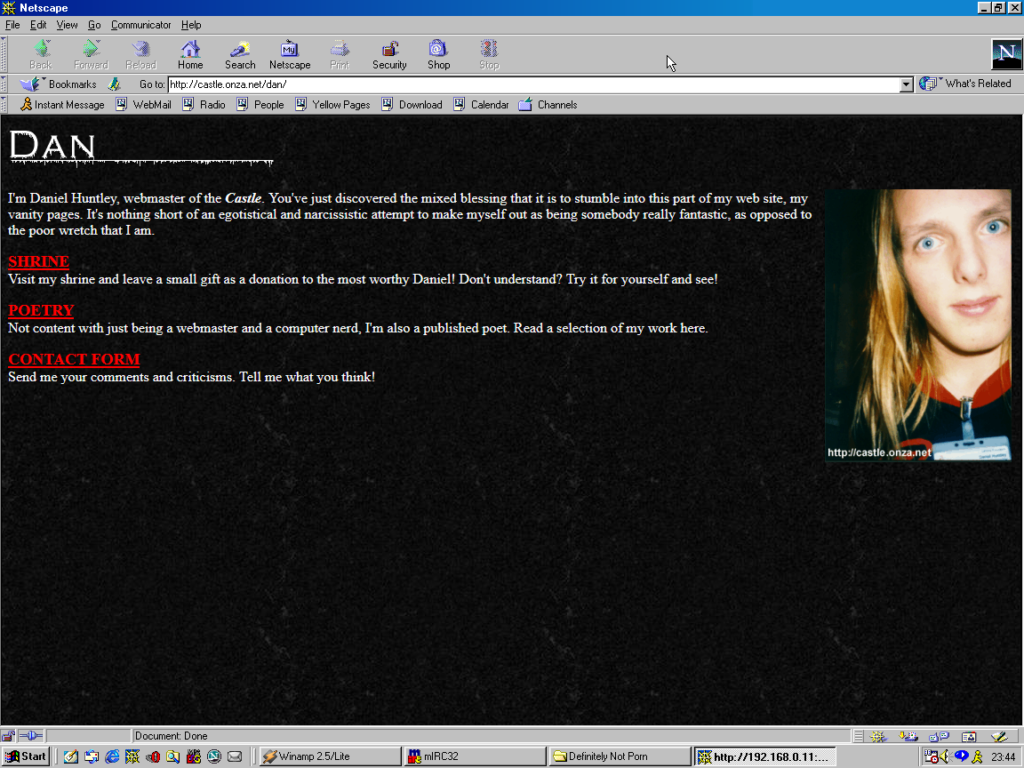

Pre-Mozilla

Netscape behaved the same way. Truly this was the de facto standard for a long period on the Web, and the varied approaches we see today are the anomaly. That’s a strange

observation to make, considering how much the Web of the 1990s was dominated by incompatible implementations of different Web features (I’ve

written about the

Pre-Mozilla

Netscape behaved the same way. Truly this was the de facto standard for a long period on the Web, and the varied approaches we see today are the anomaly. That’s a strange

observation to make, considering how much the Web of the 1990s was dominated by incompatible implementations of different Web features (I’ve

written about the <blink> and <marquee> tags before, which was perhaps the most-visible division between the Microsoft and Netscape camps, but

there were many, many more).

Interestingly: by Netscape 7.2 the browser’s behaviour had evolved to be the same as modern Firefox’s, except that it still displayed the credentials in the

address bar for all to see.

Interestingly: by Netscape 7.2 the browser’s behaviour had evolved to be the same as modern Firefox’s, except that it still displayed the credentials in the

address bar for all to see.

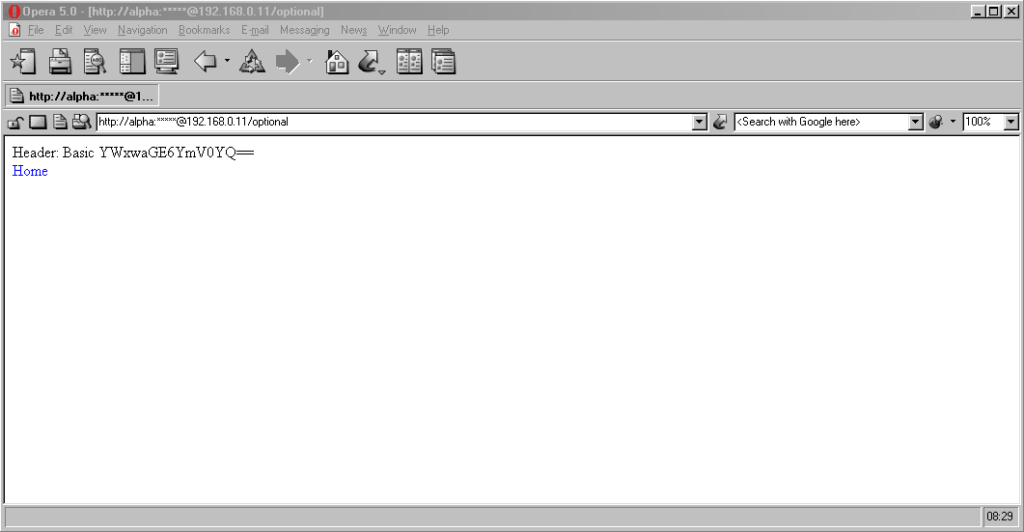

Now here’s a real

gem: pre-Chromium Opera. It would send credentials to “mandatory” pages and remember them for the duration of the browsing session, which is great. But it would also send

credentials when passed in a web address to “optional” pages. However, it wouldn’t remember them on optional pages unless they remained in the address bar: this feels to me

like an optimum balance of features for power users. Plus, it’s one of very few browsers that permitted you to change credentials mid-session: just by changing them in

the address bar! Most other browsers, even to this day, ignore changes to HTTP Authentication credentials, which was

sometimes be a source of frustration back in the day.

Now here’s a real

gem: pre-Chromium Opera. It would send credentials to “mandatory” pages and remember them for the duration of the browsing session, which is great. But it would also send

credentials when passed in a web address to “optional” pages. However, it wouldn’t remember them on optional pages unless they remained in the address bar: this feels to me

like an optimum balance of features for power users. Plus, it’s one of very few browsers that permitted you to change credentials mid-session: just by changing them in

the address bar! Most other browsers, even to this day, ignore changes to HTTP Authentication credentials, which was

sometimes be a source of frustration back in the day.

Finally, classic Opera was the only browser I’ve seen to mask the password in the address bar, turning it into a series of asterisks. This ensures the user knows that a password was used, but does not leak any sensitive information to shoulder-surfers (the length of the “masked” password was always the same length, too, so it didn’t even leak the length of the password). Altogether a spectacular design and a great example of why classic Opera was way ahead of its time.

Most people using web addresses with credentials embedded within them nowadays are probably working with code, APIs, or the command line, so it’s unsurprising to see that this is where the most “traditional” standards-compliance is found.

I was unsurprised to discover that giving curl a username and password in the URL meant that username and password was sent to the server (using Basic authentication, of course, if no authentication was requested):

$ curl http://alpha:beta@localhost/optional

Header: Basic YWxwaGE6YmV0YQ==

$ curl http://alpha:beta@localhost/mandatory

Header: Basic YWxwaGE6YmV0YQ==

However, wget did catch me out. Hitting the same addresses with wget didn’t result in the credentials being sent

except where it was mandatory (i.e. where a HTTP 401 response and a WWW-Authenticate: header was received on the initial attempt). To force wget to

send credentials when they haven’t been asked-for requires the use of the --http-user and --http-password switches:

$ wget http://alpha:beta@localhost/optional -qO-

Header:

$ wget http://alpha:beta@localhost/mandatory -qO-

Header: Basic YWxwaGE6YmV0YQ==

lynx does a cute and clever thing. Like most modern browsers, it does not submit credentials unless specifically requested, but if they’re in the address bar when they become mandatory (e.g. because of following relative hyperlinks or hyperlinks containing credentials) it prompts for the username and password, but pre-fills the form with the details from the URL. Nice.

HTTP Basic Authentication and its close cousin Digest Authentication (which overcomes some of the security limitations of running Basic Authentication over an

unencrypted connection) is very much alive, but its use in hyperlinks can’t be relied upon: some browsers (e.g. IE, Safari)

completely munge such links while others don’t behave as you might expect. Other mechanisms like Bearer see widespread use in APIs, but nowhere else.

The WWW-Authenticate: and Authorization: headers are, in some ways, an example of the best possible way to implement authentication on the Web: as an

underlying standard independent of support for forms (and, increasingly, Javascript), cookies, and complex multi-part conversations. It’s easy to imagine an alternative

timeline where these standards continued to be collaboratively developed and maintained and their shortfalls – e.g. not being able to easily log out when using most graphical browsers!

– were overcome. A timeline in which one might write a login form like this, knowing that your e.g. “authenticate” attributes would instruct the browser to send credentials using an

Authorization: header:

<form method="get" action="/" authenticate="Basic">

<label for="username">Username:</label> <input type="text" id="username" authenticate="username">

<label for="password">Password:</label> <input type="text" id="password" authenticate="password">

<input type="submit" value="Log In">

</form>

In such a world, more-complex authentication strategies (e.g. multi-factor authentication) could involve encoding forms as JSON. And single-sign-on systems would simply involve the browser collecting a token from the authentication provider and passing it on to the

third-party service, directly through browser headers, with no need for backwards-and-forwards redirects with stacks of information in GET parameters as is the case today.

Client-side certificates – long a powerful but neglected authentication mechanism in their own right – could act as first class citizens directly alongside such a system, providing

transparent second-factor authentication wherever it was required. You wouldn’t have to accept a tracking cookie from a site in order to log in (or stay logged in), and if your

browser-integrated password safe supported it you could log on and off from any site simply by toggling that account’s “switch”, without even visiting the site: all you’d be changing is

whether or not your credentials would be sent when the time came.

The Web has long been on a constant push for the next new shiny thing, and that’s sometimes meant that established standards have been neglected prematurely or have failed to evolve for

longer than we’d have liked. Consider how long it took us to get the <video> and <audio> elements because the “new shiny” Flash came to dominate,

how the Web Payments API is only just beginning to mature despite over 25 years of ecommerce on the Web, or how we still can’t

use Link: headers for all the things we can use <link> elements for despite them being semantically-equivalent!

The new model for Web features seems to be that new features first come from a popular JavaScript implementation, and then eventually it evolves into a native browser feature: for example HTML form validations, which for the longest time could only be done client-side using scripting languages. I’d love to see somebody re-think HTTP Authentication in this way, but sadly we’ll never get a 100% solution in JavaScript alone: (distributed SSO is almost certainly off the table, for example, owing to cross-domain limitations).

Or maybe it’s just a problem that’s waiting for somebody cleverer than I to come and solve it. Want to give it a go?

I got lost on the Web this week, but it was harder than I’d have liked.

There was a discussion this week in the Abnib WhatsApp group about whether a particular illustration of a farm was full of phallic imagery (it was). This left me wondering if anybody had ever tried to identify the most-priapic buildings in the world. Of course towers often look at least a little bit like their architects were compensating for something, but some – like the Ypsilanti Water Tower in Michigan pictured above – go further than others.

I quickly found the Wikipedia article for the Most Phallic Building Contest in 2003, so that was my jumping-off point. It’s easy enough to get lost on Wikipedia alone, but sometimes you feel the need for a primary source. I was delighted to discover that the web pages for the Most Phallic Building Contest are still online 18 years after the competition ended!

Link rot is a serious problem on the Web, to such an extent that it’s pleasing when it isn’t present. The other year, for example, I revisited a post I wrote in 2004 and was pleased to find that a linked 2003 article by Nicholas ‘Aquarion’ Avenell is still alive at its original address! Contrast Jonathan Ames, the author/columnist/screenwriter who created the Most Phallic Building Contest until as late as 2011 before eventually letting his site and blog lapse and fall off the Internet. It takes effort to keep Web content alive, but it’s worth more effort than it’s sometimes given.

Anyway: a shot tower in Bristol – a part of the UK with a long history of leadworking – was among the latecomer entrants to the competition, and seeing this curious building reminded me about something I’d read, once, about the manufacture of lead shot. The idea (invented in Bristol by a plumber called William Watts) is that you pour molten lead through a sieve at the top of a tower, let surface tension pull it into spherical drops as it falls, and eventually catch it in a cold water bath to finish solidifying it. I’d seen an animation of the process, but I’d never seen a video of it, so I went about finding one.

British Pathé‘s YouTube Channel provided me with this 1950 film, and if you follow only one hyperlink from this article, let it be this one! It’s a well-shot (pun intended, but there’s a worse pun in the video!), and while I needed to translate all of the references to “hundredweights” and “Fahrenheit” to measurements that I can actually understand, it’s thoroughly informative.

But there’s a problem with that video: it’s been badly cut from whatever reel it was originally found on, and from about 1 minute and 38 seconds in it switches to what is clearly a very different film! A mother is seen shepherding her young daughter off to bed, and a voiceover says:

Bedtime has a habit of coming round regularly every night. But for all good parents responsibility doesn’t end there. It’s just the beginning of an evening vigil, ears attuned to cries and moans and things that go bump in the night. But there’s no reason why those ears shouldn’t be your neighbours ears, on occasion.

Now my interest’s piqued. What was this short film going to be about, and where could I find it? There’s no obvious link; YouTube doesn’t even make it easy to find the video uploaded “next” by a given channel. I manipulated some search filters on British Pathé’s site until I eventually hit upon the right combination of magic words and found a clip called Radio Baby Sitter. It starts off exactly where the misplaced prior clip cut out, and tells the story of “Mr. and Mrs. David Hurst, Green Lane, Coventry”, who put a microphone by their daughter’s bed and ran a wire through the wall to their neighbours’ radio’s speaker so they can babysit without coming over for the whole evening.

It’s a baby monitor, although not strictly a radio one as the title implies (it uses a signal wire!), nor is it groundbreakingly innovative: the first baby monitor predates it by over a decade, and it actually did use radiowaves! Still, it’s a fun watch, complete with its contemporary fashion, technology, and social structures. Here’s the full thing, re-merged for your convenience:

Wait, what was I trying to do when I started, again? What was I even talking about…

It used to be easier than this to get lost on the Web, and sometimes I miss that.

Obviously if you go back far enough this is true. Back when search engines were much weaker and Internet content was much less homogeneous and more distributed, we used to engage in this kind of meandering walk all the time: we called it “surfing” the Web. Second-generation Web browsers even had names, pretty often, evocative of this kind of experience: Mosaic, WebExplorer, Navigator, Internet Explorer, IBrowse. As people started to engage in the noble pursuit of creating content for the Web they cross-linked their sources, their friends, their affiliations (remember webrings? here’s a reminder; they’re not quite as dead as you think!), your favourite sites etc. You’d follow links to other pages, then follow their links to others still, and so on in that fashion. If you went round the circles enough times you’d start seeing all those invariably-blue hyperlinks turn purple and know you’d found your way home.

But even after that era, as search engines started to become a reliable and powerful way to navigate the wealth of content on the growing Web, links still dominated our exploration. Following a link from a resource that was linked to by somebody you know carried the weight of a “web of trust”, and you’d quickly come to learn whose links were consistently valuable and on what subjects. They also provided a sense of community and interconnectivity that paralleled the organic, chaotic networks of acquaintances people form out in the real world.

In recent times, that interpersonal connectivity has, for many, been filled by social networks (let’s ignore their failings in this regard for now). But linking to resources “outside” of the big social media silos is hard. These advertisement-funded services work hard to discourage or monetise activity that takes you off their platform, even at the expense of their users. Instagram limits the number of external links by profile; many social networks push for resharing of summaries of content or embedding content from other sources, discouraging engagement with the wider Web, Facebook and Twitter both run external links through a linkwrapper (which sometimes breaks); most large social networks make linking to the profiles of other users of the same social network much easier than to users anywhere else; and so on.

The net result is that Internet users use fewer different websites today than they did 20 years ago, and spend most of their “Web” time in app versions of websites (which often provide a better experience only because site owners strategically make it so to increase their lock-in and data harvesting potential). Truly exploring the Web now requires extra effort, like exercising an underused muscle. And if you begin and end your Web experience on just one to three services, that just feels kind of… sad, to me. Wasted potential.

It sounds like I’m being nostalgic for a less-sophisticated time on the Web (that would certainly be in character!). A time before we’d fully-refined the technology that would come to connect us in an instant to the answers we wanted. But that’s not exactly what I’m pining for. Instead, what I miss is something we lost along the way, on that journey: a Web that was more fun-and-weird, more interpersonal, more diverse. More Geocities, less Facebook; there’s a surprising thing to find myself saying.

Somewhere along the way, we ended up with the Web we asked for, but it wasn’t the Web we wanted.