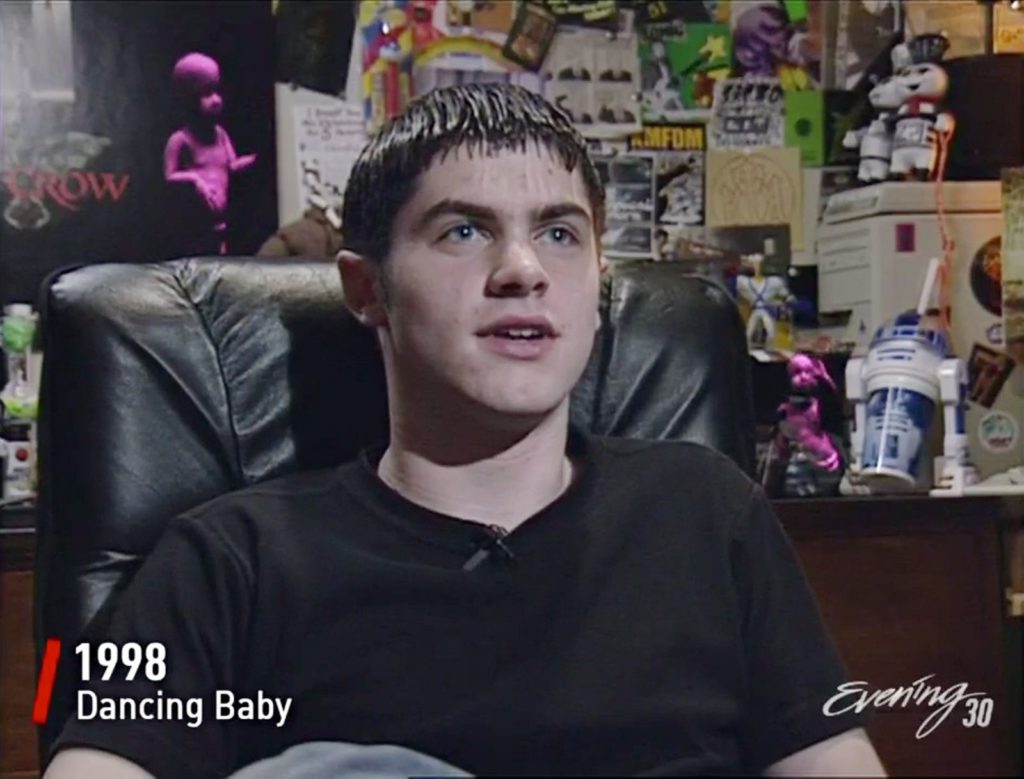

Official Post from Rob Sheridan: That goober you see above is me as a nerdy high school kid in my bedroom in 1998, being interviewed on TV for a dumb website I made. Allow me to explain.20 years ago this month, an episode of the TV show Ally McBeal featured a strange animated baby dancing the cha-cha in a vision experienced by the

That goober you see above is me as a nerdy high school kid in my bedroom in 1998, being interviewed on TV for a dumb website I made. Allow me to explain.

20 years ago this month, an episode of the TV show Ally McBeal featured a strange animated baby dancing the cha-cha in a vision experienced by the show’s titular character. It immediately became an unlikely pop culture sensation, and by the tail end of the 90s you couldn’t pass a mall t-shirt kiosk or a Spencer’s Gifts without seeing corny merchandise for The Dancing Baby, or “Oogachaka Baby” as it was sometimes known. This child of the Uncanny Valley was an offensively banal phenomenon: It had no depth, no meaning, no commentary, no narrative. It was just a dumb video loop from the internet, something your nerdiest co-worker would have emailed you for a ten-second chuckle. We know these frivolous bite-sized jokes as memes now, and they’re wildly pervasive in popular culture. You can get every type of Grumpy Cat merchandise imaginable, for example, despite the property being nothing more than a photo of a cranky-looking feline with some added text. We know what memes are in 2018 but in 1997, we didn’t. The breathtaking stupidity of The Dancing Baby’s popularity was a strange development with online origins that had no cultural precedent. It’s a cringe-worthy thing to look back on, appropriately relegated to the dumpster of regrettable 90s fads. But I have a confession to make: The Dancing Baby was kinda my fault.

…

Internet memes of the 1990s were a very different beast to those you see today. A combination of the slow connection speeds, lower population of “netizens” (can you believe we used to call ourselves that), and the fact that many of the things we take for granted today were then cutting-edge or experimental technologies like animated GIFs or web pages with music means that memes spread more-slowly and lived for longer. Whereas today a meme can be born and die in the fraction of a heartbeat that it takes for you to discover them, the memes of 1990s grew gradually and truly organically: there was not yet any market for attempting to “manufacture” a meme. If if you were thoroughly plugged-in to Net culture, by the time you discovered a new meme it could be weeks or months old and still thriving, and spin-off memes (like the dozens of sites that followed the theme of the Hampster Dance) almost existed to pay homage to the originals, rather than in an effort to supplant them.

I’m aware that meme culture predates the dancing baby, and I had the privilege of seeing it foster on e.g. newsgroups beforehand. But the early Web provided a fascinating breeding ground for a new kind of meme: one that brushed up against mainstream culture and helped to put the Internet onto more people’s mental maps: consider the media reaction to the appearance of the Dancing Baby on Ally McBeal. So as much as you might want to wrap your hands around the throat of the greasy teenager in the picture, above, I think that in a way we should be thanking him for his admittedly-accidental work in helping bring geek culture into the sight of popular culture.

And I’m not just saying that because I, too, spent the latter half of the 1990s putting things online that I ought to by right have been embarassed by in hindsight. ;-)

0 comments