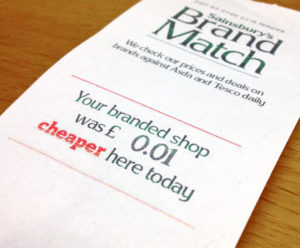

It’s been almost five years since Sainsbury’s supermarkets pioneered the “brand match” idea, which rivals Tesco and Asda later adopted into their own schemes, and I maintain that it’s one of the cleverest pieces of marketing that I’ve ever seen. In case you’ve not come across it before, the principle is this: if your shopping would have been cheaper at one of their major competitors, these supermarkets will give you a voucher for the difference right there at the checkout. Properly advertised (e.g. not in ways that get banned for being misleading), these schemes are an incredibly-compelling tool: no consumer should say no to getting the best possible prices without having to shop around, right?

But it’s nowhere near as simple as that. For a start, the terms and conditions (Asda, Sainsbury’s, Tesco) put significant limitations on how the schemes work. You need to buy at least a certain number of items (8 at Asda, 10 at the other two). Those items must be directly-comparable to competitors’ items: which basically means that only branded products count, but even among them, the competitor must stock the exact same size or else it doesn’t count, even if it would have been cheaper to buy two half-sized products there. There are upper limits to the value of the vouchers (usually £10) and the number that you can use per transaction or per month. “Buy X get Y free” offers are excluded. And there’s a huge list of not-compared products which may include batteries, toys, DVDs, some alcoholic drinks, cosmetics, homeware, flowers, baby formula, light bulbs, books, and anything (even non-medicines) from the pharmacy aisle.

But even if it only applies to some of your shopping – the stuff that’s easy to directly compare – it’s still a good deal, right? You’re getting money back towards what you would have saved if you’d have gone up the road? Not necessarily. Let us assume that on average the prices of these three supermarket giants are pretty much the same. Individual products might each be a little more expensive here and a little cheaper there, but if you buy a large enough trolley-load you’re not going to notice the difference. Following me so far? What does this mean for the voucher: it means that it no longer remotely represents what you would have saved if you’d actually been “shopping around”. Let’s take a concrete example:

Suppose that this is my somewhat-eccentric shopping list (I wanted to select a variety of comparable branded products), and I’m considering shopping at either Sainsbury’s or Tesco:

- Mozzarella

- Fish fingers

- Clover spread

- Whole milk

- Crunch corner yoghurts

- Fromage frais

- Cadbury Mini Rolls

- Frozen chips

- Frozen petit pois

- Goodfella’s deep pan pizza

- Dough balls

- Chocolate-dipped flapjacks

- Dry white wine

- Bagels

- Multigrain wraps

- Red Bull multipack

- Angel Slices

- Cheerios

- Windolene

- Cornettos

Not too unreasonable, right? I’ve made a spreadsheet showing my working, where you’ll see today’s prices for each of these items (along with the actual brands and package sizes I’ve selected), if you’d like to check my maths, because here comes the clever bit.

Based on my calculation, taking my imaginary shopping list to Sainsbury’s will ultimately cost me £52.85. Taking it to Tesco will cost me £54.13. Pretty close, right, and I’m not likely to care about the

difference because Tesco would give me a £1.28 voucher off my next shop which makes up for the difference (note that Sainsbury’s wouldn’t reciprocate in kind if it were the other way

around, after a policy change they made late last year). But that’s not

actually a true representation of the value of ‘shopping around’. As my spreadsheet shows, if I were to buy each item on my list at the supermarket that was cheapest, it’d only cost me

a total of £43.75: that’s a saving of £9.10 (or about 17% off my entire shop) compared to the cheapest of these supermarkets. These schemes don’t give

you a real “best of all worlds”. Instead, they give you, at most, a “best of all worlds, assuming that you’re still going to be lazy enough to only shop in one place”.

If you’re particularly devious of mind, you can exploit this. For example, suppose I went to Tesco but when I reached the checkout I split my shopping into two transactions.

The first transaction contains the frozen goods, milk, wine, dough balls, flapjacks, and mini rolls. This comes out at £33.73, which is £10.38 more than Sainsbury’s would charge me for the same goods. Tesco

therefore gives me a £10 voucher, which I immediately use on the second batch of shopping: the one which contains goods that are cheaper than their Sainsbury’s

equivalents. The total price of my shopping: £44.13 – only 38p more than if I’d gone to both

supermarkets and bought only the best-value goods from each (the 38p discrepancy comes from the fact that Tesco won’t ever give you a voucher worth more than £10, no matter how much

you’re losing out).

It’s not even that hard to do. Obviously, somebody’s probably written an app for it, but even if you’re just doing it by guesswork you can get a better result than just piling all of your shopping onto the conveyor belt together. Simply put the things which seem like a good deal (all of the discounted products, plus anything that feels like it’s good value) at one end of your trolley, and unload those things last. Making sure that you’ve got at least ten items on the conveyor, ‘split’ your shopping somewhere towards the beginning of these items. Then take any voucher you get from your first load, and apply it to the second.

It’s pretty easy, so long as you don’t mind looking like a bit of a tool at the checkout.

But to most people, most of the time, this is nothing more than a strong and compelling piece of marketing. Either you get reminded that you allegedly “saved money”, on a piece of paper that probably goes into your wallet and helps to combat buyer’s remorse, or else we get told that we paid a particular amount more than we needed to, and are offered the difference back so long as we return to the same store within the next fortnight. Either way, the supermarket wins your loyalty, which – for a couple of pence on each transaction (assuming that the customer doesn’t lose the voucher or otherwise fail to get an opportunity to use it) – is a miniscule price to pay.

Amazing! There are words in there that I have no idea what they are. Mainly your last two on the shopping list.

So a tl;dr for anyone, places want your money. Even if it seems like a good deal do your own work and you can get a better deal. Even though you might look like a tool

:)

Windolene is a window-cleaning chemical in a pump-action spray bottle. I think the closest major brand elsewhere in the world would be Windex.

Cornettos are an ice cream product from Walls (or Streets in Australia). I believe that Nestlé’s competing product Drumsticks are the best-known alternative elsewhere in the world? Cornettos are iconic thanks to the memorable “opera singer ad” which ran during the 80s and 90s, and also because they’re repeatedly referenced in Edgar Wright/Simon Pegg’s (excellent) film trilogy: Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and The World’s End.