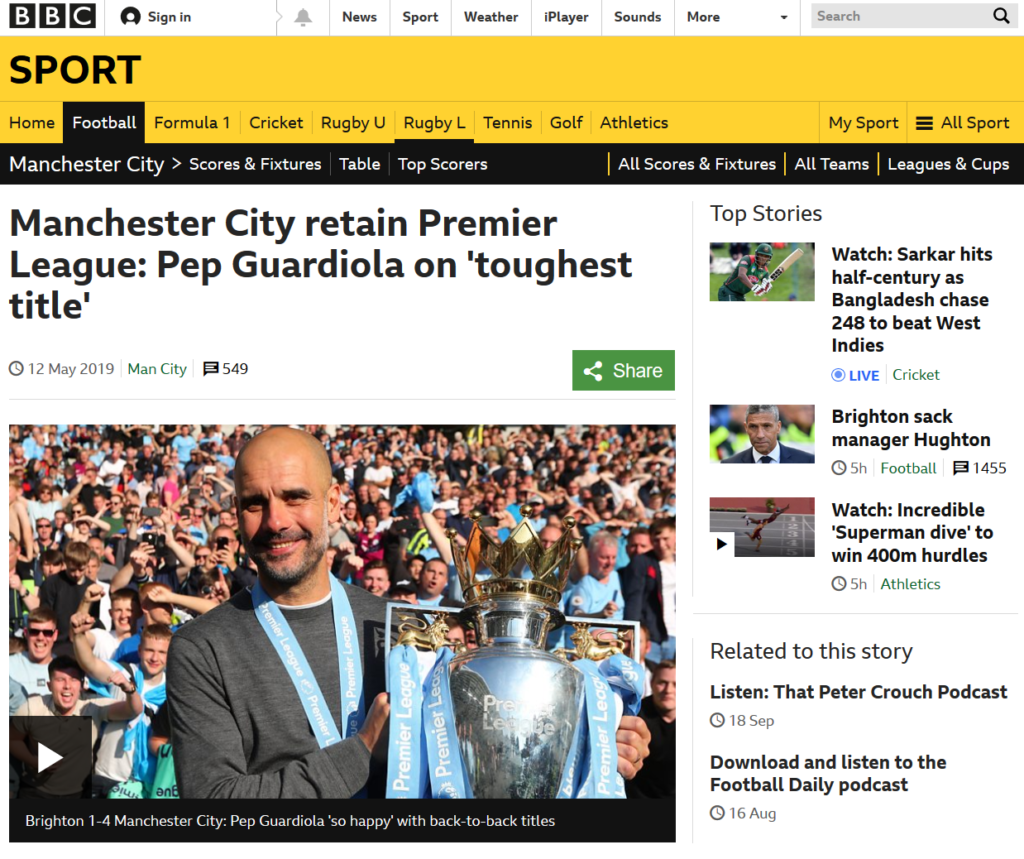

The Beeb continue to keep adding more and more non-news content to the BBC News RSS feed (like this ad for the iPlayer app!), so I’ve once again had to update my script to “fix” the feed so that it only contains, y’know, news.

Tag: ruby

BBC News… without the crap

Did I mention recently that I love RSS? That it brings me great joy? That I start and finish almost every day in my feed reader? Probably.

I used to have a single minor niggle with the BBC News RSS feed: that it included sports news, which I didn’t care about. So I wrote a script that downloaded it, stripped sports news, and re-exported the feed for me to subscribe to. Magic.

But lately – presumably as a result of technical changes at the Beeb’s side – this feed has found two fresh ways to annoy me:

-

The feed now re-publishes a story if it gets re-promoted to the front page… but with a different

<guid>(it appears to get a #0 after it when first published, a #1 the second time, and so on). In a typical day the feed reader might scoop up new stories about once an hour, any by the time I get to reading them the same exact story might appear in my reader multiple times. Ugh. - They’ve started adding iPlayer and BBC Sounds content to the BBC News feed. I don’t follow BBC News in my feed reader because I want to watch or listen to things. If you do, that’s fine, but I don’t, and I’d rather filter this content out.

Luckily, I already have a recipe for improving this feed, thanks to my prior work. Let’s look at my newly-revised script (also available on GitHub):

#!/usr/bin/env ruby require 'bundler/inline' # # Sample crontab: # # At 41 minutes past each hour, run the script and log the results # */20 * * * * ~/bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.rb > ~/bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.log 2>>&1 # Dependencies: # * open-uri - load remote URL content easily # * nokogiri - parse/filter XML gemfile do source 'https://rubygems.org' gem 'nokogiri' end require 'open-uri' # Regular expression describing the GUIDs to reject from the resulting RSS feed # We want to drop everything from the "sport" section of the website, also any iPlayer/Sounds links REJECT_GUIDS_MATCHING = /^https:\/\/www\.bbc\.co\.uk\/(sport|iplayer|sounds)\// # Load and filter the original RSS rss = Nokogiri::XML(open('https://feeds.bbci.co.uk/news/rss.xml?edition=uk')) rss.css('item').select{|item| item.css('guid').text =~ REJECT_GUIDS_MATCHING }.each(&:unlink) # Strip the anchors off the <guid>s: BBC News "republishes" stories by using guids with #0, #1, #2 etc, which results in duplicates in feed readers rss.css('guid').each{|g|g.content=g.content.gsub(/#.*$/,'')} File.open( '/www/bbc-news-no-sport.xml', 'w' ){ |f| f.puts(rss.to_s) }

That revised script removes from the feed anything whose <guid> suggests it’s sports news or from BBC Sounds or iPlayer, and also strips any “anchor” part of the

<guid> before re-exporting the feed. Much better. (Strictly speaking, this can result in a technically-invalid feed by introducing duplicates, but your feed reader

oughta be smart enough to compensate for and ignore that: mine certainly is!)

You’re free to take and adapt the script to your own needs, or – if you don’t mind being tied to my opinions about what should be in BBC News’ RSS feed – just subscribe to my copy at: https://fox.q-t-a.uk/bbc-news-no-sport.xml

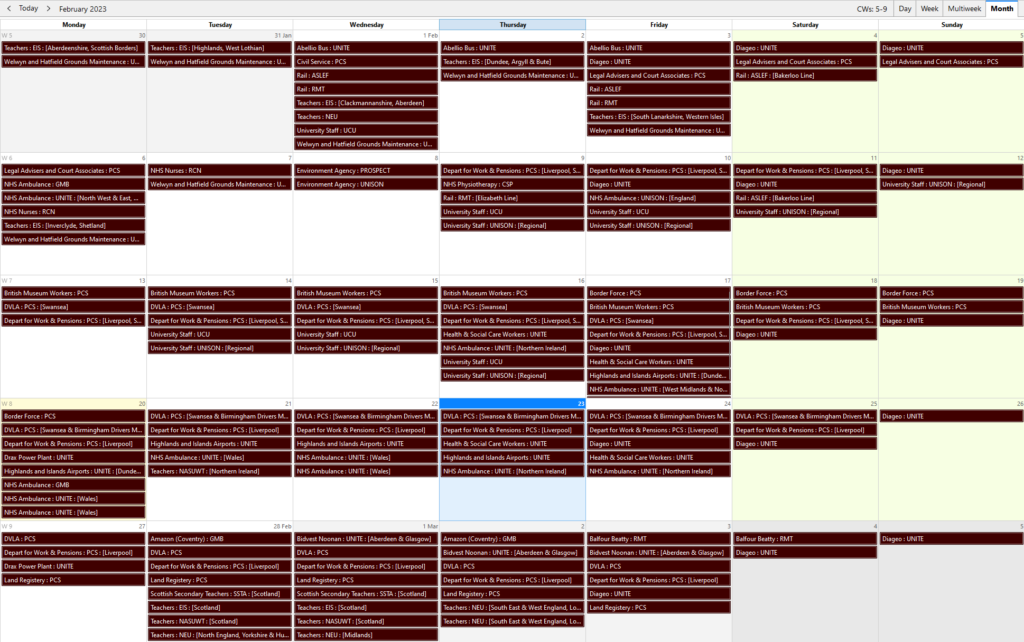

UK Strikes in .ics Format

My work colleague Simon was looking for a way to add all of the upcoming UK strike action to their calendar, presumably so they know when not to try to catch a bus or require an ambulance or maybe just so they’d know to whom they should be giving support on any particular day. Thom was able to suggest a few places to see lists of strikes, such as this BBC News page and the comprehensive strikecalendar.co.uk, but neither provided a handy machine-readable feed.

If only they knew somebody who loves an excuse to throw a screen-scraper together. Oh wait, that’s me!

I threw together a 36-line Ruby program that extracts all the data from strikecalendar.co.uk and outputs an

.ics file. I guess if you wanted you could set it up to automatically update the file a couple of times a day and host it at a URL that people can subscribe to; that’s an exercise left for the reader.

If you just want a one-off import based on the state-of-play right now, though, you can save this .ics file to your computer and import it to your calendar. Simple.

Nginx Caching for Passenger Applications

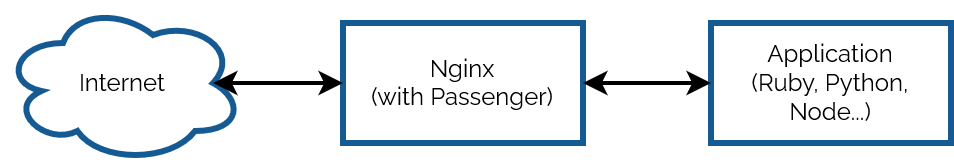

Suppose you’re running an application on a Passenger + Nginx powered server and you want to add caching.

Perhaps your application has a dynamic, public endpoint but the contents don’t change super-frequently or it isn’t critically-important that the user always gets up-to-the-second accuracy, and you’d like to improve performance with microcaching. How would you do that?

Where you’re at

Your configuration might look something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

server { # listen, server_name, ssl, logging etc. directives go here # ... root /your/application; passenger_enabled on; } |

What you’re looking for is proxy_cache and its sister directives, but you can’t just

insert them here because while Passenger does act act like an upstream proxy (with parallels like e.g. passenger_pass_header which mirrors the behaviour of proxy_pass_header), it doesn’t provide any of the functions you need to implement proxy caching

of non-static files.

Where you need to be

Instead, what you need to to is define a second server, mount Passenger in that, and then proxy to that second server. E.g.:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

# Set up a cache proxy_cache_path /tmp/cache/my-app-cache keys_zone=MyAppCache:10m levels=1:2 inactive=600s max_size=100m; # Define the actual webserver that listens for Internet traffic: server { # listen, server_name, ssl, logging etc. directives go here # ... # You can configure different rules by location etc., but here's a simple microcache: location / { proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:4863; # Proxy all traffic to the application server defined below proxy_cache MyAppCache; # Use the cache defined above proxy_cache_valid 200 3s; # Treat HTTP 200 responses as valid; cache them for 3 seconds proxy_cache_use_stale updating; # (Optional) send outdated response while background-updating cache proxy_cache_lock on; # (Optional) only allow one process to update cache at once } } # (Local-only) application server on an arbitrary port number to act as the upstream proxy: server { listen 127.0.0.1:4863; root /your/application; passenger_enabled on; } |

The two key changes are:

- Passenger moves to a second

serverblock, localhost-only, on an arbitrary port number (doesn’t need HTTPS, of course, but if your application detects/”expects” HTTPS you might need to tweak your headers). - Your main

serverblock proxies to the second as its upstream, and you can add whatever caching directives you like.

Obviously you’ll need to be smarter if you host a mixture of public and private content (e.g. send Vary: headers from your application) and if you want different cache

durations on different addresses or types of content, but there are already great guides to help with that. I only wrote this post because I spent some time searching for (nonexistent!)

passenger_cache_ etc. rules and wanted to save the next person from the same trouble!

LABS Comic RSS Archive

Yesterday I recommended that you go read Aaron Uglum‘s webcomic LABS which had just completed its final strip. I’m a big fan of “completed” webcomics – they feel binge-able in the same way as a complete Netflix series does! – but Spencer quickly pointed out that it’s annoying for we enlightened modern RSS users who hook RSS up to everything to have to binge completed comics in a different way to reading ongoing ones: what he wanted was an RSS feed covering the entire history of LABS.

So naturally (after the intense heatwave woke me early this morning anyway) I made one: complete RSS feed of LABS. And, of course, I open-sourced the code I used to generate it so that others can jumpstart their projects to make static RSS feeds from completed webcomics, too.

Even if you’re not going to read it via this medium, you should go read LABS.

BBC News… without the sport

I love RSS, but it’s a minor niggle for me that if I subscribe to any of the BBC News RSS feeds I invariably get all the sports news, too. Which’d be fine if I gave even the slightest care about the world of sports, but I don’t.

It only takes a couple of seconds to skim past the sports stories that clog up my feed reader, but because I like to scratch my own

itches, I came up with a solution. It’s more-heavyweight perhaps than it needs to be, but it does the job. If you’re just looking for a BBC News (UK) feed but with sports filtered

out you’re welcome to share mine: https://f001.backblazeb2.com/file/Dan–Q–Public/bbc-news-nosport.rss https://fox.q-t-a.uk/bbc-news-no-sport.xml.

If you’d like to see how I did it so you can host it yourself or adapt it for some similar purpose, the code’s below or on GitHub:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby # # Sample crontab: # # At 41 minutes past each hour, run the script and log the results # 41 * * * * ~/bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.rb > ~/bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.log 2>&1 # Dependencies: # * open-uri - load remote URL content easily # * nokogiri - parse/filter XML # * b2 - command line tools, described below require 'bundler/inline' gemfile do source 'https://rubygems.org' gem 'nokogiri' end require 'open-uri' # Regular expression describing the GUIDs to reject from the resulting RSS feed # We want to drop everything from the "sport" section of the website REJECT_GUIDS_MATCHING = /^https:\/\/www\.bbc\.co\.uk\/sport\// # Assumption: you're set up with a Backblaze B2 account with a bucket to which # you'd like to upload the resulting RSS file, and you've configured the 'b2' # command-line tool (https://www.backblaze.com/b2/docs/b2_authorize_account.html) B2_BUCKET = 'YOUR-BUCKET-NAME-GOES-HERE' B2_FILENAME = 'bbc-news-nosport.rss' # Load and filter the original RSS rss = Nokogiri::XML(open('https://feeds.bbci.co.uk/news/rss.xml?edition=uk')) rss.css('item').select{|item| item.css('guid').text =~ REJECT_GUIDS_MATCHING }.each(&:unlink) begin # Output resulting filtered RSS into a temporary file temp_file = Tempfile.new temp_file.write(rss.to_s) temp_file.close # Upload filtered RSS to a Backblaze B2 bucket result = `b2 upload_file --noProgress --contentType application/rss+xml #{B2_BUCKET} #{temp_file.path} #{B2_FILENAME}` puts Time.now puts result.split("\n").select{|line| line =~ /^URL by file name:/}.join("\n") ensure # Tidy up after ourselves by ensuring we delete the temporary file temp_file.close temp_file.unlink end

bbc-news-rss-filter-sport-out.rb

When executed, this Ruby code:

- Fetches the original BBC news (UK) RSS feed and parses it as XML using Nokogiri

- Filters it to remove all entries whose GUID matches a particular regular expression (removing all of those from the “sport” section of the site)

- Outputs the resulting feed into a temporary file

- Uploads the temporary file to a bucket in Backblaze‘s “B2” repository (think: a better-value competitor S3); the bucket I’m using is publicly-accessible so anybody’s RSS reader can subscribe to the feed

I like the versatility of the approach I’ve used here and its ability to perform arbitrary mutations on the feed. And I’m a big fan of Nokogiri. In some ways, this could be considered a lower-impact, less real-time version of my tool RSSey. Aside from the fact that it won’t (easily) handle websites that require Javascript, this approach could probably be used in exactly the same ways as RSSey, and with significantly less set-up: I might look into whether its functionality can be made more-generic so I can start using it in more places.

Linda Liukas, Hello Ruby and the magic of coding

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Linda Liukas’s best-selling Hello Ruby books teach children that computers are fun and coding can be a magical experience.

See the original article to watch a great video interview with Linda Liukas. Linda is the founder of Rails Girls and author of a number of books encouraging children to learn computer programming (which I’m hoping to show copies of to ours, when they’re a tiny bit older). I’ve mentioned before how important I feel an elementary understanding of programming concepts is to children.

The Ruby Story

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

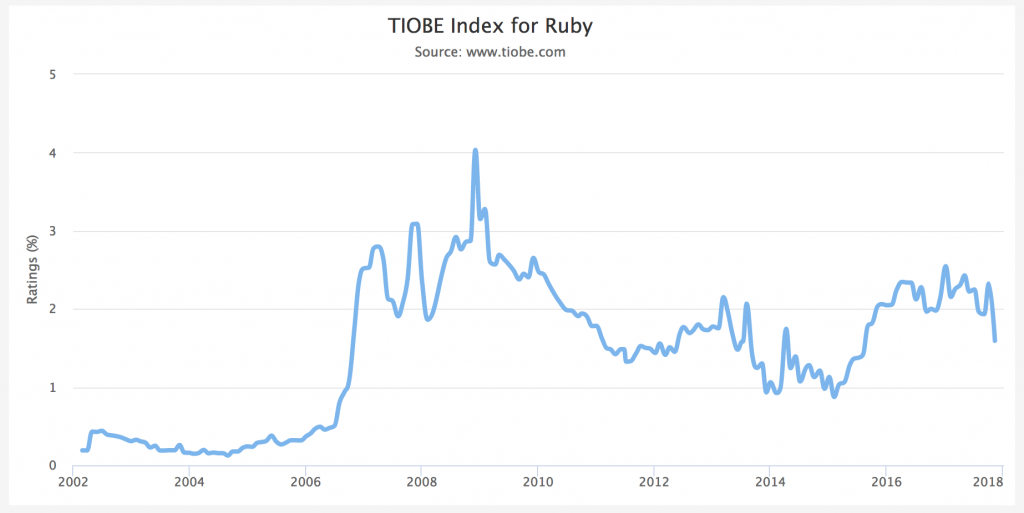

By 2005, Ruby had become more popular, but it was still not a mainstream programming language. That changed with the release of Ruby on Rails. Ruby on Rails was the “killer app” for Ruby, and it did more than any other project to popularize Ruby. After the release of Ruby on Rails, interest in Ruby shot up across the board, as measured by the TIOBE language index:

It’s sometimes joked that the only programs anybody writes in Ruby are Ruby-on-Rails web applications. That makes it sound as if Ruby on Rails completely took over the Ruby community, which is only partly true. While Ruby has certainly come to be known as that language people write Rails apps in, Rails owes as much to Ruby as Ruby owes to Rails.

…

As an early adopter of Ruby (and Rails, when it later came along) I’ve always found that it brings me a level of joy I’ve experienced in very few other languages (and never as much). Every time I write Ruby, it takes me back to being six years old and hacking BASIC on my family’s microcomputer. Ruby, more than any other language I’ve come across, achieves the combination of instant satisfaction, minimal surprises, and solid-but-flexible object orientation. There’s so much to love about Ruby from a technical perspective, but for me: my love of it is emotional.

Why it is just lazy to bad-mouth Ruby on Rails

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

It’s inevitable these days: we will see an article proclaiming the demise of Ruby on Rails every once in a while. It’s the easiest click bait, like this one from TNW.Now, you may say “another Ruby fanboy.” That’s fair, but a terrible argument, as it’s a poor and common argumentum ad hominem. And on the subject of fallacies, the click-bait article above is wrong exactly because it falls for a blatantly Post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy plus some more confirmation bias which we are all guilty of falling for all the time. I’m not saying that the author wrote fallacies on purpose. Unfortunately, it’s just too easy to fall for fallacies. Especially when everybody has an intrinsic desire to confirm one’s biases. Even trying to be careful, I end up doing that as well…

Rails is f*cking boring! I love it.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Together with a friend I recently built Dropshare Cloud. We offer online storage for the file and screenshot sharing app Dropshare for macOS/iOS. After trying out Django for getting started (we both had some experience using Django) I decided to rewrite the codebase in Rails. My past experience developing in Rails made the process quick — and boring…

15 Weird Things About Ruby That You Should Know

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Ruby is an amazing language with a lot of interesting details that you may not have seen before…

What Does Jack FM Sound Like?

Those who know me well know that I’m a bit of a data nerd. Even when I don’t yet know what I’m going to do with some data yet, it feels sensible to start collecting it in a nice machine-readable format from the word go. Because you never know, right? That’s how I’m able to tell you how much gas and electricity our house used on average on any day in the last two and a half years (and how much off that was offset by our solar panels).

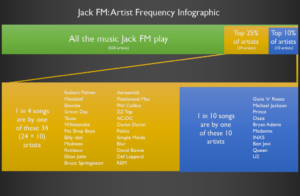

So it should perhaps come as no huge surprise that for the last six months I’ve been recording the identity of every piece of music played by my favourite local radio station, Jack FM (don’t worry: I didn’t do this by hand – I wrote a program to do it). At the time, I wasn’t sure whether there was any point to the exercise… in fact, I’m still not sure. But hey: I’ve got a log of the last 45,000 songs that the radio station played: I might as well do something with it. The Discogs API proved invaluable in automating the discovery of metadata relating to each song, such as the year of its release (I wasn’t going to do that by hand either!), and that gave me enough data to, for example, do this (click on any image to see a bigger version):

I almost expected a bigger variance by hour-of-day, but I guess that Jack isn’t in the habit of pandering to its demographics too heavily. I spotted the post-midnight point at which you get almost a plurality of music from 1990 or later, though: perhaps that’s when the young ‘uns who can still stay up that late are mostly listening to the radio? What about by day-of-week, then:

The chunks of “bonus 80s” shouldn’t be surprising, I suppose, given that the radio station advertises that that’s exactly what it does at those times. But still: it’s reassuring to know that when a radio station claims to play 80s music, you don’t just have to take their word for it (so long as their listeners include somebody as geeky as me).

It feels to me like every time I tune in they’re playing an INXS song. That can’t be a coincidence, right? Let’s find out:

Yup, there’s a heavy bias towards Guns ‘n’ Roses, Michael Jackson, Prince, Oasis, Bryan Adams, Madonna, INXS, Bon Jovi, Queen, and U2 (who collectively are responsible for over a tenth of all music played on Jack FM), and – to a lesser extent – towards Robert Palmer, Meatloaf, Blondie, Green Day, Texas, Whitesnake, the Pet Shop Boys, Billy Idol, Madness, Rainbow, Elton John, Bruce Springsteen, Aerosmith, Fleetwood Mac, Phil Collins, ZZ Top, AC/DC, Duran Duran, the Police, Simple Minds, Blur, David Bowie, Def Leppard, and REM: taken together, one in every four songs played on Jack FM is by one of these 34 artists.

I was interested to see that the “top 20 songs” played on Jack FM these last six months include several songs by artists who otherwise aren’t represented at all on the station. The most-played song is Alice Cooper’s Poison, but I’ve never recorded them playing any other Alice Cooper songs (boo!). The fifth-most-played song is Fight For Your Right, by the Beastie Boys, but that’s the only Beastie Boys song I’ve caught them playing. And the seventh-most-played – Roachford’s Cuddly Toy – is similarly the only Roachford song they ever put on.

Next I tried a Markov chain analysis. Markov chains are a mathematical tool that examines a sequence (in this case, a sequence of songs) and builds a map of “chains” of sequential songs, recording the frequency with which they follow one another – here’s a great explanation and playground. The same technique is used by “predictive text” features on your smartphone: it knows what word to suggest you type next based on the patterns of words you most-often type in sequence. And running some Markov chain analysis helped me find some really… interesting patterns in the playlists. For example, look at the similarities between what was played early in the afternoon of Wednesday 19 October and what was played 12 hours later, early in the morning of Thursday 20 October:

| 19 October 2016 | 20 October 2016 | ||

| 12:06:33 | Kool & The Gang – Fresh | Kool & The Gang – Fresh | 00:13:56 |

| 12:10:35 | Bruce Springsteen – Dancing In The Dark | Bruce Springsteen – Dancing In The Dark | 00:17:57 |

| 12:14:36 | Maxi Priest – Close To You | Maxi Priest – Close To You | 00:21:59 |

| 12:22:38 | Van Halen – Why Can’t This Be Love | Van Halen – Why Can’t This Be Love | 00:25:00 |

| 12:25:39 | Beats International / Lindy – Dub Be Good To Me | Beats International / Lindy – Dub Be Good To Me | 00:29:01 |

| 12:29:40 | Kasabian – Fire | Kasabian – Fire | 00:33:02 |

| 12:33:42 | Talk Talk – It’s My Life | Talk Talk – It’s My Life | 00:38:04 |

| 12:41:44 | Lenny Kravitz – Are You Gonna Go My Way | Lenny Kravitz – Are You Gonna Go My Way | 00:42:05 |

| 12:45:45 | Shalamar – I Can Make You Feel Good | Shalamar – I Can Make You Feel Good | 00:45:06 |

| 12:49:47 | 4 Non Blondes – What’s Up | 4 Non Blondes – What’s Up | 00:50:07 |

| 12:55:49 | Madness – Baggy Trousers | Madness – Baggy Trousers | 00:54:09 |

| Eagle Eye Cherry – Save Tonight | 00:56:09 | ||

| Feeling – Love It When You Call | 01:04:12 | ||

| 13:02:51 | Fine Young Cannibals – Good Thing | Fine Young Cannibals – Good Thing | 01:10:14 |

| 13:06:54 | Blur – There’s No Other Way | Blur – There’s No Other Way | 01:14:15 |

| 13:09:55 | Pet Shop Boys – It’s A Sin | Pet Shop Boys – It’s A Sin | 01:17:16 |

| 13:14:56 | Zutons – Valerie | Zutons – Valerie | 01:22:18 |

| 13:22:59 | Cure – The Love Cats | Cure – The Love Cats | 01:26:19 |

| 13:27:01 | Bryan Adams / Mel C – When You’re Gone | Bryan Adams / Mel C – When You’re Gone | 01:30:20 |

| 13:30:02 | Depeche Mode – Personal Jesus | Depeche Mode – Personal Jesus | 01:33:21 |

| 13:34:03 | Queen – Another One Bites The Dust | Queen – Another One Bites The Dust | 01:38:22 |

| 13:42:06 | Shania Twain – That Don’t Impress Me Much | Shania Twain – That Don’t Impress Me Much | 01:42:23 |

| 13:45:07 | ZZ Top – Gimme All Your Lovin’ | ZZ Top – Gimme All Your Lovin’ | 01:46:25 |

| 13:49:09 | Abba – Mamma Mia | Abba – Mamma Mia | 01:50:26 |

| 13:53:10 | Survivor – Eye Of The Tiger | Survivor – Eye Of The Tiger | 01:53:27 |

| Scouting For Girls – Elvis Aint Dead | 01:57:28 | ||

| Verve – Lucky Man | 02:00:29 | ||

| Fleetwood Mac – Say You Love Me | 02:05:30 | ||

| 14:03:13 | Kiss – Crazy Crazy Nights | Kiss – Crazy Crazy Nights | 02:10:31 |

| 14:07:15 | Lightning Seeds – Sense | Lightning Seeds – Sense | 02:14:33 |

| 14:11:16 | Pretenders – Brass In Pocket | Pretenders – Brass In Pocket | 02:18:34 |

| 14:14:17 | Elvis Presley / JXL – A Little Less Conversation | Elvis Presley / JXL – A Little Less Conversation | 02:21:35 |

| 14:22:19 | U2 – Angel Of Harlem | U2 – Angel Of Harlem | 02:24:36 |

| 14:25:20 | Trammps – Disco Inferno | Trammps – Disco Inferno | 02:28:37 |

| 14:29:22 | Cast – Guiding Star | Cast – Guiding Star | 02:31:38 |

| 14:33:23 | New Order – Blue Monday | New Order – Blue Monday | 02:36:39 |

| 14:41:26 | Def Leppard – Let’s Get Rocked | Def Leppard – Let’s Get Rocked | 02:40:41 |

| 14:46:28 | Phil Collins – Sussudio | Phil Collins – Sussudio | 02:45:42 |

| 14:50:30 | Shawn Mullins – Lullaby | Shawn Mullins – Lullaby | 02:49:43 |

| 14:55:31 | Stars On 45 – Stars On 45 | Stars On 45 – Stars On 45 | 02:53:45 |

| 16:06:35 | Dead Or Alive – You Spin Me Round Like A Record | Dead Or Alive – You Spin Me Round Like A Record | 03:00:47 |

| 16:09:36 | Dire Straits – Walk Of Life | Dire Straits – Walk Of Life | 03:03:48 |

| 16:13:37 | Keane – Everybody’s Changing | Keane – Everybody’s Changing | 03:07:49 |

| 16:17:39 | Billy Idol – Rebel Yell | Billy Idol – Rebel Yell | 03:10:50 |

| 16:25:41 | Stealers Wheel – Stuck In The Middle | Stealers Wheel – Stuck In The Middle | 03:14:51 |

| 16:28:42 | Green Day – American Idiot | Green Day – American Idiot | 03:18:52 |

| 16:33:44 | A-Ha – Take On Me | A-Ha – Take On Me | 03:21:53 |

| 16:36:45 | Cranberries – Dreams | Cranberries – Dreams | 03:26:54 |

| Elton John – Philadelphia Freedom | 03:30:56 | ||

| Inxs – Disappear | 03:36:57 | ||

| Kim Wilde – You Keep Me Hanging On | 03:40:59 | ||

| 16:44:47 | Living In A Box – Living In A Box | ||

| 16:47:48 | Status Quo – Rockin’ All Over The World | Status Quo – Rockin’ All Over The World | 03:45:00 |

The similarities between those playlists (which include a 20-songs-in-a-row streak!) surely can’t be coincidence… but they do go some way to explaining why listening to Jack FM sometimes gives me a feeling of déjà vu (along with, perhaps, the no-talk, all-jukebox format). Looking elsewhere in the data I found dozens of other similar occurances, though none that were both such long chains and in such close proximity to one another. What does it mean?

There are several possible explanations, including:

- The exotic, e.g. they’re using Markov chains to control an auto-DJ, and so just sometimes it randomly chooses to follow a long chain that it “learned” from a real DJ.

- The silly, e.g. Jack FM somehow knew that I was monitoring them in this way and are trying to troll me.

- My favourite: these two are actually the same playlist, but with breaks interspersed differently. During the daytime, the breaks in the list are more-frequent and longer, which suggests: ad breaks! Advertisers are far more-likely to pay for spots during the mid-afternoon than they are in the middle of the night (the gap in the overnight playlist could well be a short ad or a jingle), which would explain why the two are different from one another!

But the question remains: why reuse playlists in close proximity at all? Even when the station operates autonomously, as it clearly does most of the time, it’d surely be easy enough to set up an auto-DJ using “smart random” (because truly random shuffles don’t sound random to humans) to get the same or a better effect.

Which leads to another interesting observation: Jack FM’s sister stations in Surrey and Hampshire also maintain a similar playlist most of the time… which means that they’re either synchronising their ad breaks (including their duration – I suspect this is the case) or else using filler jingles to line-up content with the beginnings and ends of songs. It’s a clever operation, clearly, but it’s not beyond black-box comprehension. More research is clearly needed. (And yes, I’m sure I could just call up and ask – they call me “Newcastle Dan” on the breakfast show – but that wouldn’t be even half as fun as the data mining is…)

Ruby is still great! · Hendrik Mans

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I realized something today:

Ruby is still great.

I’ve spent the last couple of weeks digging into some of the newer/fancier/shinier technologies that have been in the limelight of the development world lately – specifically Elixir, Phoenix and Elm – and while I’ve thoroughly enjoyed them all (and instantly had a bunch of fun ideas for things to build with them), I also realized once more how much I like Ruby, and what kind of project it’s still a great choice for…

Non-Rails Frameworks in Ruby: Cuba, Sinatra, Padrino, Lotus

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

It’s common for a Ruby developer to describe themselves as a Rails developer. It’s also common for someone’s entire Ruby experience to be through Rails. Rails began in 2003 by David Heinemeier Hansson, quickly becoming the most popular web framework and also serving as an introduction to Ruby for many developers.

Rails is great. I use it every day for my job, it was my introduction to Ruby, and this is the most fun I’ve ever had as a developer. That being said, there are a number of great framework options out there that aren’t Rails.

This article intends to highlight the differences between Cuba, Sinatra, Padrino, Lotus, and how they compare to or differ from Rails. Let’s have a look at some Non-Rails Frameworks in Ruby.

My Favourite Ruby (am I doing this right?)

This link was originally posted to /r/MegaLoungeRuby. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: https://www.ruby-lang.org/

[this post was originally made to a private subreddit]