2680 REM SET UP CASTLE

2690 DIM A(19,7):CHECKSUM=0

2700 FOR B=1 TO 19

2710 FOR C=1 TO 7

2720 READ A(B,C):CHECKSUM=CHECKSUM+A(B,C)

2730 NEXT C:NEXT B

2740 IF CHECKSUM<>355 THEN PRINT "ERROR IN ROOM DATA":END

...

2840 REM ALLOT TREASURE

2850 FOR J=1 TO 7

2860 M=INT(RND*19)+1

2870 IF M=6 OR M=11 OR A(M,7)<>0 THEN 2860

2880 A(M,7)=INT(RND*100)+100

2890 NEXT J

2910 REM ALLOT MONSTERS

2920 FOR J=1 TO 6

2930 M=INT(RND*18)+1

2940 IF M=6 OR M=11 OR A(M,7)<>0 THEN 2930

2950 A(M,7)=-J

2960 NEXT J

2970 A(4,7)=100+INT(RND*100)

2980 A(16,7)=100+INT(RND*100)

...

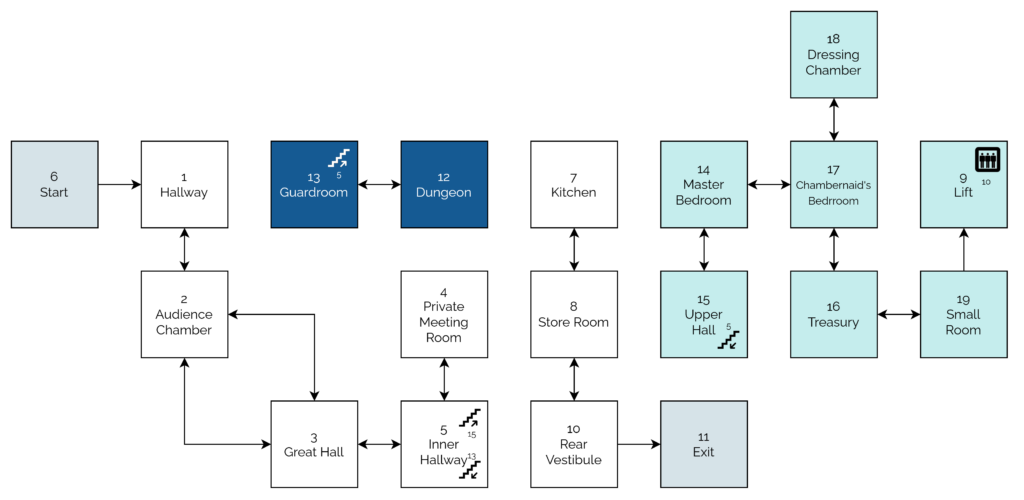

3310 DATA 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

3320 DATA 1, 3, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0

3330 DATA 2, 0, 5, 2, 0, 0, 0

3340 DATA 0, 5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

3350 DATA 4, 0, 0, 3, 15, 13, 0

3360 DATA 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0

3370 DATA 0, 8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

3380 DATA 7, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

3390 DATA 0, 19, 0, 8, 0, 8, 0

3400 DATA 8, 0, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0

3410 DATA 0, 0, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0

3420 DATA 0, 0, 0, 13, 0, 0, 0

3430 DATA 0, 0, 12, 0, 5, 0, 0

3440 DATA 0, 15, 17, 0, 0, 0, 0

3450 DATA 14, 0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 0

3460 DATA 17, 0, 19, 0, 0, 0, 0

3470 DATA 18, 16, 0, 14, 0, 0, 0

3480 DATA 0, 17, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

3490 DATA 9, 0, 16, 0, 0, 0, 0

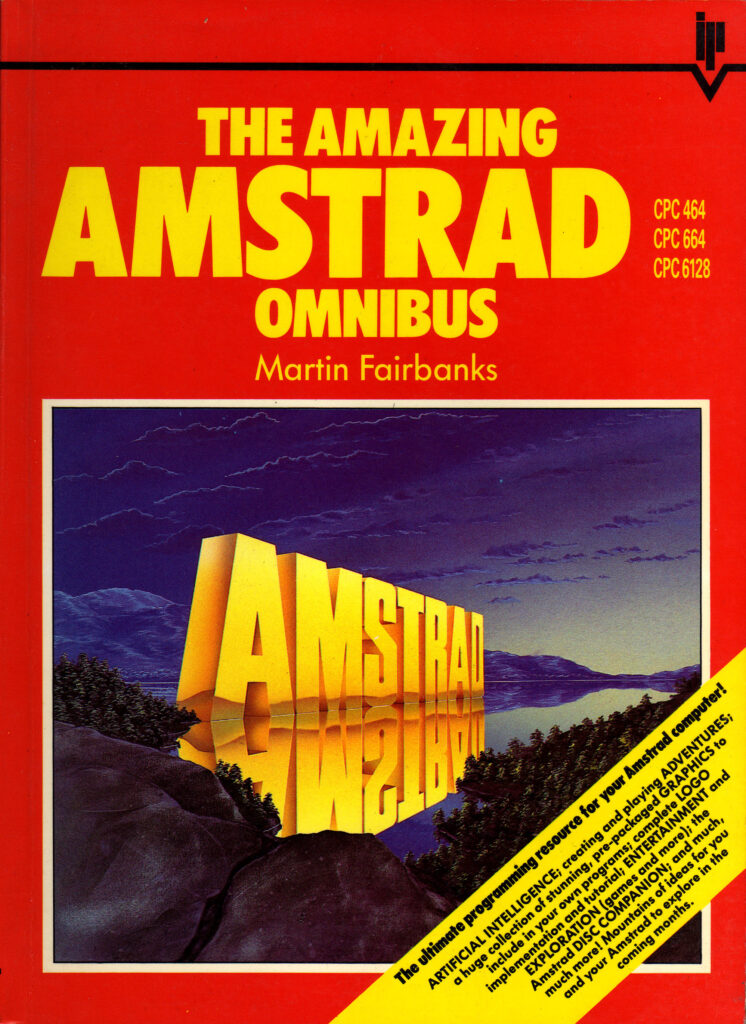

![Scan of a ring-bound page from a technical manual. The page describes the use of the "INPUT" command, saying "This command is used to let the computer know that it is expecting something to be typed in, for example, the answer to a question". The page goes on to provide a code example of a program which requests the user's age and then says "you look younger than [age] years old.", substituting in their age. The page then explains how it was the use of a variable that allowed this transaction to occur.](/_q23u/2023/07/cpc664-manual-input-command.png)