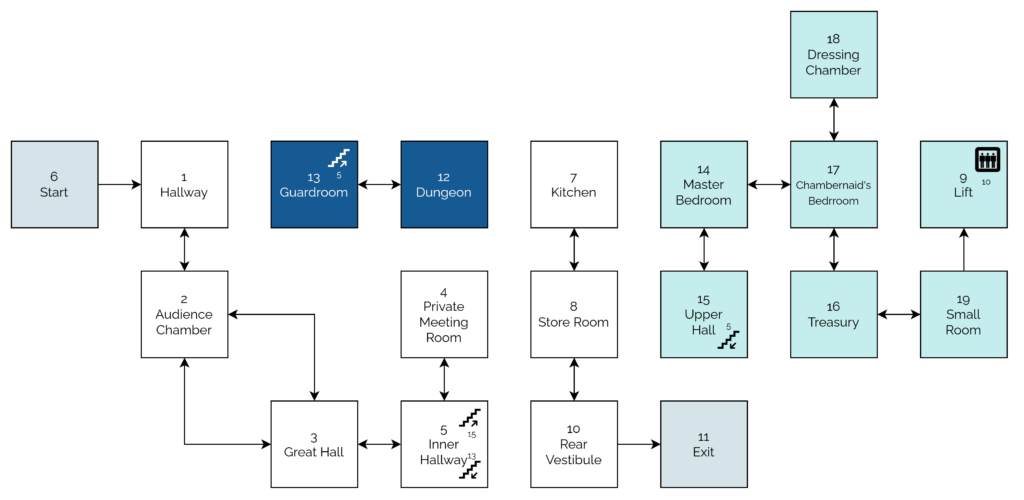

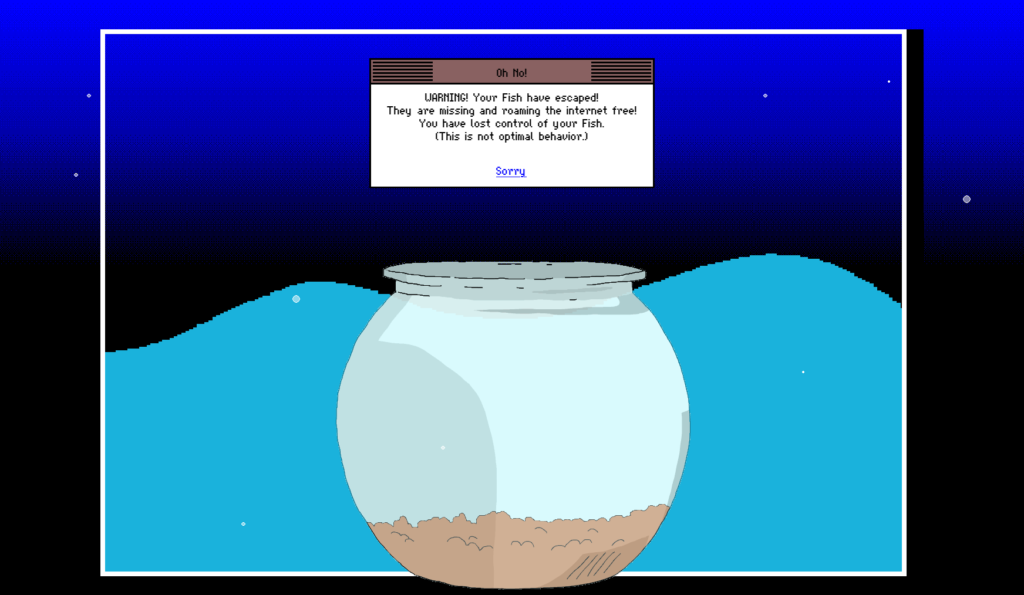

A Castle Built From Random Rooms is a work in progress/early access/demo version of a full game that’ll probably never exist. But if it does exist, it will be basically the same as this, but on a grander scale, and include the following features:

– over a hundred random rooms instead of about ten

– character jobs and descriptions that actually add individualised effects/skills/starting equipment and so on

– special pre-chosen characters with particulalrly challenging stats levels for extra difficult challenges

– more stats! more items! more use of the stats and items within different rooms to create different outcomes!

– high scores and loot rankings and possibly even achievements of some kind

– less bugs (aspiration)

– decent endings (stretch goal)What the game almost certainly won’t ever have:

– any semblance of quality or coherence

– sound and/or music

– monetary success

I saw and first played this ages ago, after its initial release was mentioned on Metafilter Projects last year. In case you missed it first time around, you can give it a go now!

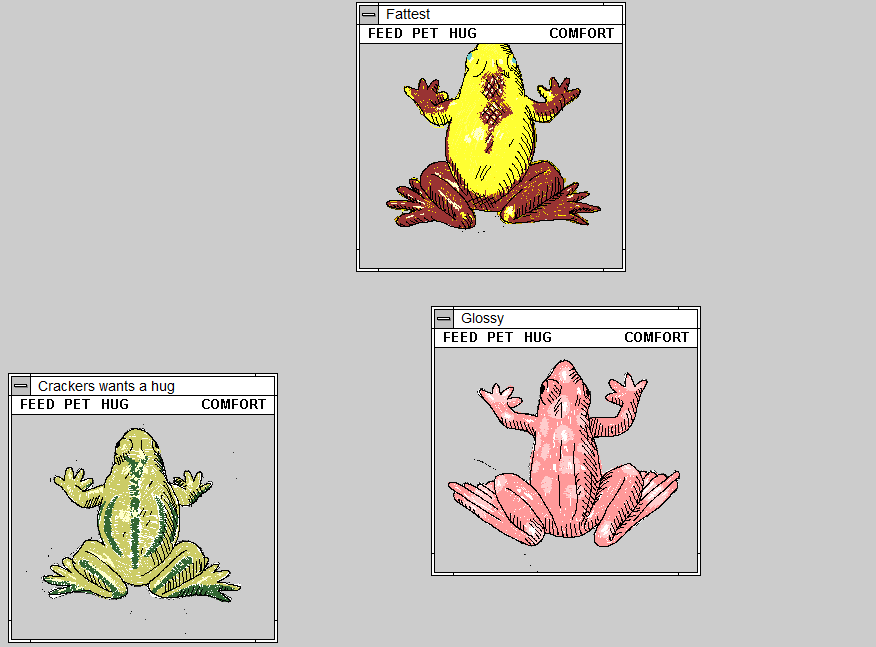

It’s a Twine-like choose-your-own-adventure, but with the rooms randomly shuffled each time, in sort-of a semi-rougelite way. Some imaginative work in this. And the art style is wonderful!

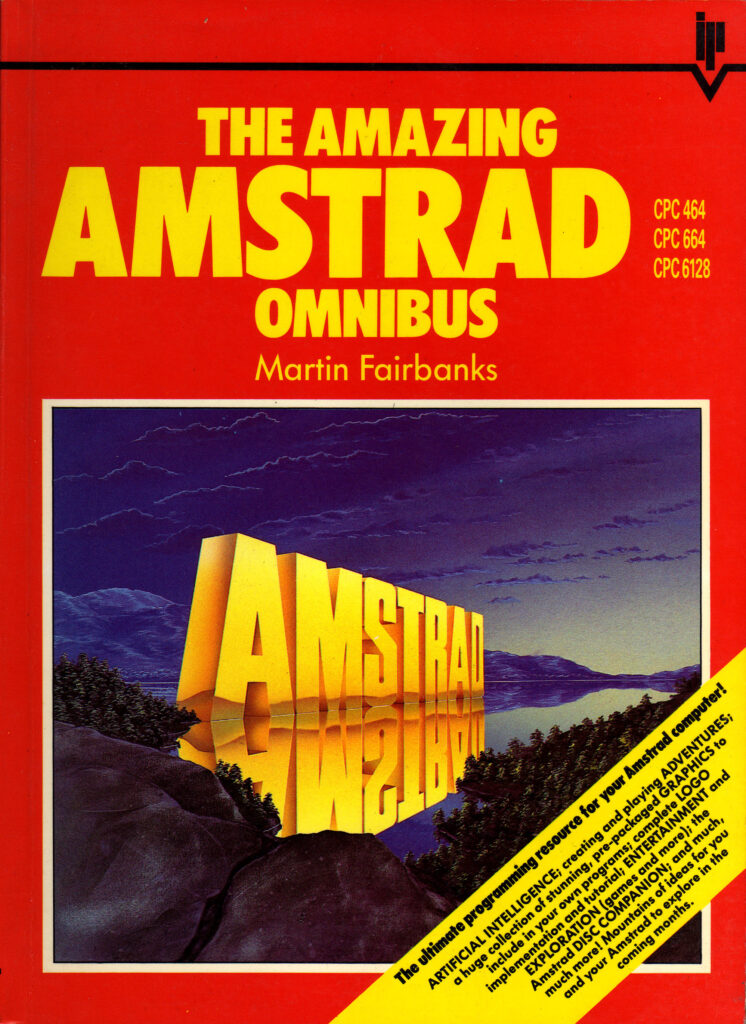

![Scan of a ring-bound page from a technical manual. The page describes the use of the "INPUT" command, saying "This command is used to let the computer know that it is expecting something to be typed in, for example, the answer to a question". The page goes on to provide a code example of a program which requests the user's age and then says "you look younger than [age] years old.", substituting in their age. The page then explains how it was the use of a variable that allowed this transaction to occur.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2023/07/cpc664-manual-input-command.png)