…

A common rebuttal I get to this…

What about when you want to keep global styles out of your component, like with a third-party widget that gets loaded on lots of different pages?

I kind-of sort-of see the logic in that. But I also think wanting your component to not look like a cohesive part of the page its loaded into is weird and unexpected.

…

I so-rarely disagree with Chris on JavaScript issues, but I think I kinda do on this one. I fully agree that the Shadow DOM is usually a bad idea and its encapsulation concept encourages exactly the kind of over-narrow componentised design thinking that React also suffers from. But I think that the rebuttal Chris picks up on is valid… just sometimes.

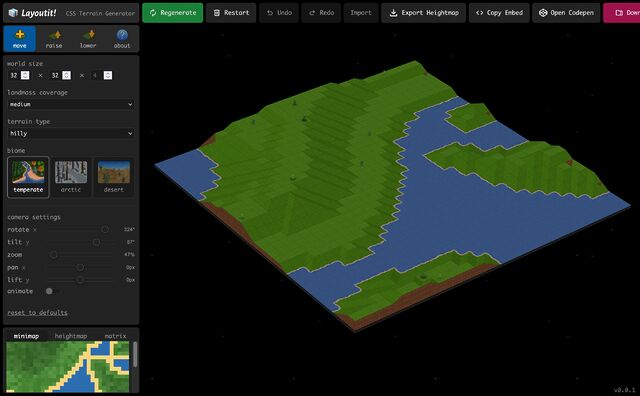

When I created the Beige Buttons component earlier this year, I used the shadow DOM. It was the first time I’ve done so: I’ve always rejected it in my previous (HTML) Web Components for exactly the reasons Chris describes. But I maintain that it was, in this case, the right tool for the job. The Beige Buttons aren’t intended to integrate into the design of the site on which they’re placed, and allowing the site’s CSS to interact with some parts of it – such as the “reset” button – could fundamentally undermine the experience it intends to create!

I appreciate that this is an edge case, for sure, and most Web Component libraries almost certainly shouldn’t use the shadow DOM. But I don’t think it’s valid to declare it totally worthless.

That said, I’ve not yet had the opportunity to play with Cascade Layers, which – combined with directives like all: reset;, might provide a way to strongly

override the style of components without making it impossibly hard for a site owner to provide their own customised experience. I’m still open to persuasion!