This checkin to GC8X701 War Memorial #1191 ~ Lichfield reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Morning geowalk while on a visit from Oxfordshire. Super quiet, no stealth needed this morning!

This checkin to GC8X701 War Memorial #1191 ~ Lichfield reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Morning geowalk while on a visit from Oxfordshire. Super quiet, no stealth needed this morning!

This checkin to GC93KP4 Lichfield TB Resort & Spa reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Spent a frankly embarrassing amount of time hunting in all the wrong places before spotting the obvious difference between this hotel and the other (non travel bug) ones nearby. Excellent container, FP awarded.

Greetings from Oxfordshire! I’m up for a show and to visit family and woke early this morning for a spot of caching before breakfast. I’d perhaps not have woken so early if my hotel were as nice as this one! (I may have to deploy something like this in my neck of the woods…)

This checkin to GC4KHZ4 One in a Million - Festival Gardens reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

No luck for me this morning. Based on recent logs and photos I suspect the object to which the hint relates was repaired recently and the cache muggled at the same time.

This checkin to GC7QG1Z Oxford’s Wild Wolf Three reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Temporarily disabled pending repair of Stage 2.

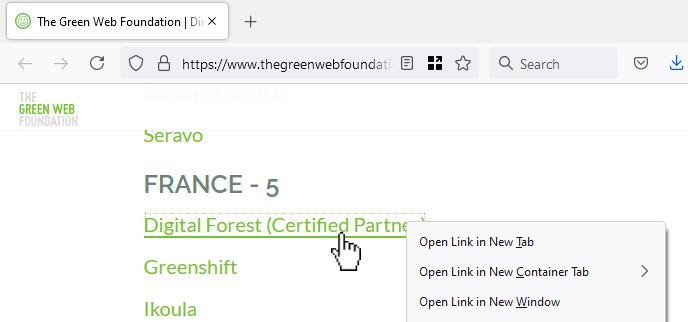

I’ve written before about the trend in web development to take what the web gives you for free, throw it away, and then rebuild it in Javascript. The rebuilt version is invariably worse in many ways – less-accessible, higher-bandwidth, reduced features, more fragile, etc. – but it’s more convenient for developers. Personally, I try not to value developer convenience at the expense of user experience, but that’s an unpopular opinion lately.

In the site shown in the screenshot above, the developer took something the web gave them for free (a hyperlink), threw it away (by making it a link-to-nowhere), and rebuilt its functionality with Javascript (without thinking about the fact that you can do more with hyperlinks than click them: you can click-and-drag them, you can bookmark them, you can share them, you can open them in new tabs etc.). Ugh.

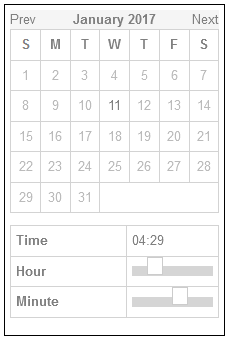

Particularly egregious are the date pickers. Entering your date of birth on a web form ought to be pretty simple: gov.uk pretty much solved it based on user testing they did in 2013.

Here’s the short of it:

<select> elements keyboard

users can still “type” to filter.

<select>s but are really funky React <div>s, is pretty terrible.

My fellow Automattician Enfys recently tweeted:

People designing webforms that require me to enter my birthdate:

I am begging you: just let me type it in.

Typing it in is 6-8 quick keystrokes. Trying to navigate a little calendar or spinny wheels back to the 1970s is time-consuming, frustrating and unnecessary.

They’re right. Those little spinny wheels are a pain in the arse if you’ve got to use one to go back 40+ years.

If there’s one thing we learned from making the worst volume control in the world, the other year, it’s that you can always find a worse UI metaphor. So here’s my attempt at making a date of birth field that’s somehow even worse than “date spinners”:

My datepicker implements a game of “higher/lower”. Starting from bounds specified in the HTML code and a random guess, it narrows-down its guess as to what your date of birth is as you click the up or down buttons. If you make a mistake you can start over with the restart button.

Amazingly, this isn’t actually the worst datepicker into which I’ve entered my date of birth! It’s cognitively challenging compared to most, but it’s relatively fast at narrowing down the options from any starting point. Plus, I accidentally implemented some good features that make it better than plenty of the datepickers out there:

<input type="date"> control, your browser takes responsibility for localising, so if you’re from one of those weird countries that prefers

mm-dd-yyyy then that’s what you should see.

It turns out that even when you try to make something terrible, so long as you’re building on top of the solid principles the web gives you for free, you can accidentally end up with something not-so-bad. Who knew?

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

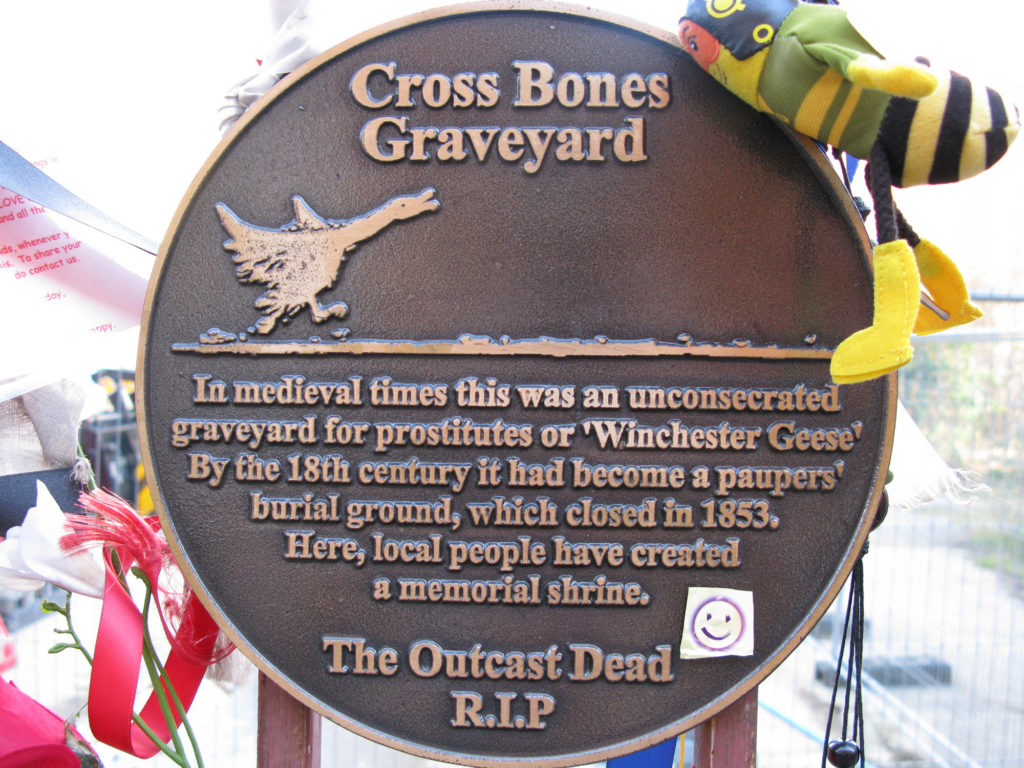

My favourite thing about geese… is the etymologies of all the phrases relating to geese. There’s so many, and they’re all amazing. I started reading about one, then – silly goose that I am – found another, and another, and another…

For example:

Geese make their way all over our vocabulary. If it’s snowing, the old woman is plucking her

goose. If it’s fair to give two people the same thing (and especially if one might consider not doing so on account of their sex), you might say that what’s good

for the goose is good for the gander, which apparently used to use

the word “sauce” instead of “good”. I’ve no idea where the idea of cooking someone’s goose comes from, nor why anybody thinks that a goose step

march might look anything like the way a goose walks waddles.

With apologies to Beverley, whose appreciation of geese (my take, previously) is something else entirely but might well have got me thinking about this in the first instance.

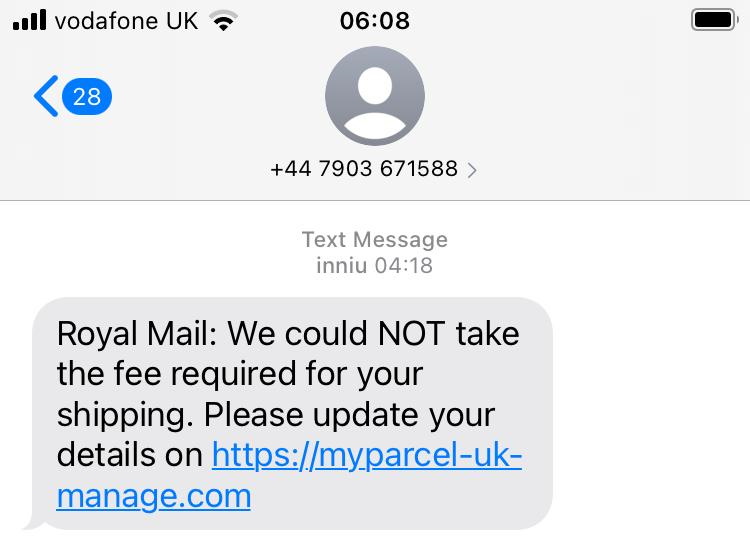

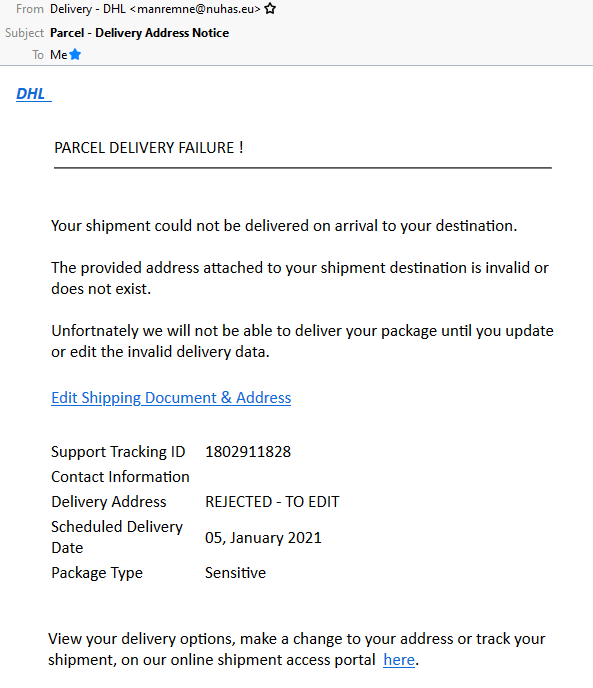

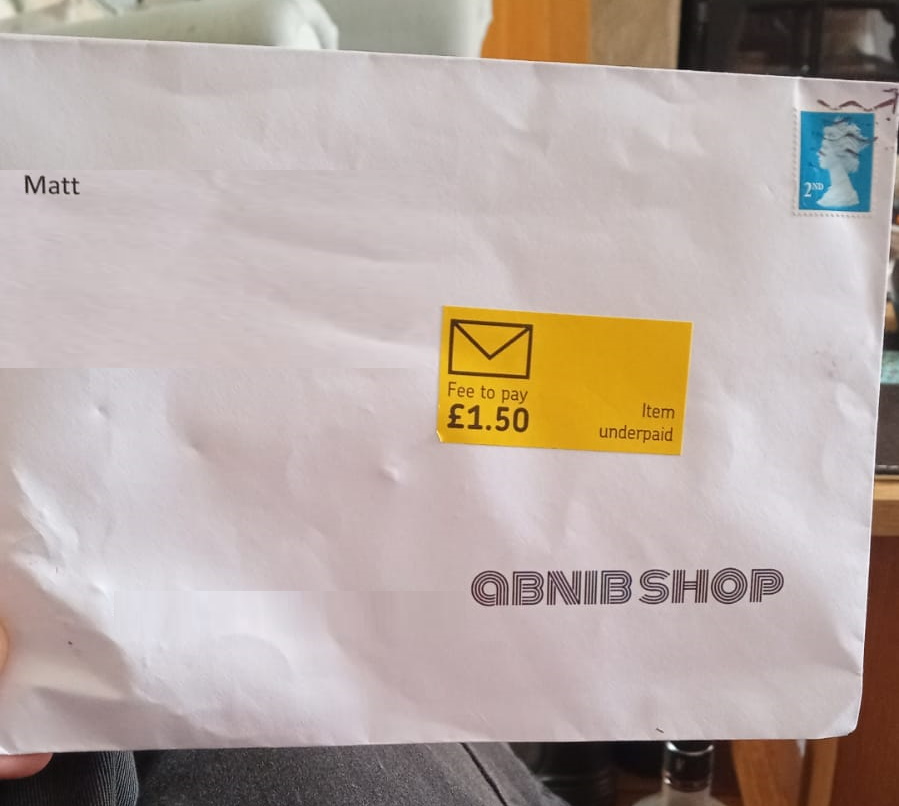

There’s a lot of talk lately about scam texts pretending to be from Royal Mail (or other parcel carriers), tricking victims into paying a fee to receive a parcel. Hearing of recent experiences with this sort of scam inspired me to dissect the approach the scammers use… and to come up with ways in which the scams could be more-effective.

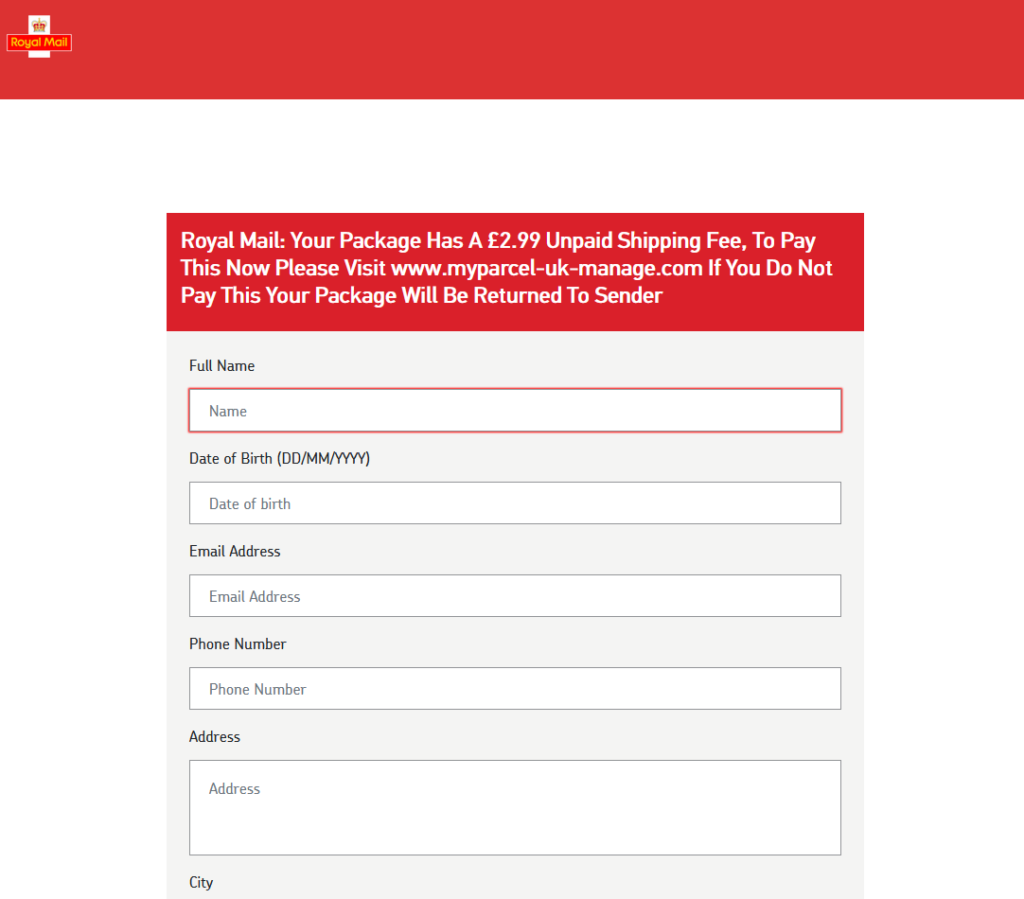

Let’s take a look at a scam:

A parcel fee scam begins with a phishing email or, increasingly, text message, telling the victim that they need to pay a fee in order to receive a parcel and directing them to a website to make payment.

If the victim clicks the link, they’ll likely see a fake website belonging to the company who allegedly have the victim’s parcel. They’ll be asked for personal and payment information, after which they’ll be told that their parcel is scheduled for redelivery. They’ll often be redirected back to the real website as a “convincer”. The redirects often go through a third-party redirect site so that your browser’s “Referer:” header doesn’t give away the scam to the legitimate company (if it did, they could e.g. detect it and show you a “you just got scammed by somebody pretending to be us” warning!).

Many scammers also set a cookie so they’ll recognise you if you come back: if you return to the scam site with this cookie in-place, they’ll redirect you instantly to the genuine company’s site. This means that if you later try to follow the link in the text message you’ll see e.g. the real Royal Mail website, which makes it harder for you to subsequently identify that you’ve been scammed. (Some use other fingerprinting methods to detect that you’ve been victimised already, such as your IP address.)

Typically, no payment is actually taken. Often, the card number and address aren’t even validated, and virtually any input is accepted. That’s because this kind of scam isn’t about tricking you into giving the scammers money. It’s about harvesting personal information for use in a second phase.

Once the scammers have your personal information they’ll either use your card details to make purchases of hard-to-trace, easy-to-resell goods like gift cards or, increasingly, use all of the information you’ve provided in order to perform an even more-insidious trick. Knowing your personal, contact and bank details, they can convincingly call you and pretend to be your bank! Some sophisticated fraudsters will even highlight the parcel fee scam you just fell victim to in order to gain your trust and persuade you that they’re genuinely your bank, which is a very powerful convincer.

A scam like the one described above works because each individual part of it is individually convincing, but the parts are delivered separately.

Being asked to pay a fee to receive a parcel is a pretty common experience, and getting texts from carriers is too. A lot of people are getting a lot more stuff mail-ordered than they used to, right now, and that – along with the Brexit-related import duties that one in ten people have had to pay – means that it seems perfectly reasonable to get a message telling you that you need to pay a fee to get your parcel.

Similarly, I’m sure we’ve all been called by our bank to discuss a suspicious transaction. (When this happens to me, I’ve always said that I’ll call them back on the number on my card or my bank statements rather than assume that they are who they claim to be. When I first started doing this, 20 years ago, this sometimes frustrated bank policies, but nowadays they’re more accepting.) Most people though will willingly believe the legitimacy of a person who calls them up, addresses them by name and claims to be from their bank.

Separating the scam into two separate parts, each of which is individually unsuspicious, makes it more effective at tricking the victim than simpler phishing scams.

Anybody could fall for this. It’s not about being smart and savvy; lots of perfectly smart people become victims of this kind of fraud. Certainly, there are things you can do (like learning to tell a legitimate domain name from a probably-fake one and only ever talking to your bank if you were the one who initiated the call), but we’re all vulnerable sometimes. If you were expecting a delivery, and it’s really important, and you’re tired, and you’re distracted, and then a text message comes along pressuring you to pay the fee right now… anybody could make a mistake.

But do you know what: these scammers aren’t even trying that hard. There’s so much that they could be doing so much “better”. I’m going to tell you, off the top of my head, four things that they could do to amplify their effect.

Wait a minute: am I helping criminals by writing this? No, I don’t think so. I believe that these are things that they’ve thought of already. Right now, it’s just not worthwhile for them to pull out all the stops… they can make plenty of money conning people using their current methods: they don’t need to invest the time and energy into doing their shitty job better.

But if there’s one thing we’ve learned it’s that digital security is an arms race. If people stop falling for these scams, the criminals will up their game. And they don’t need me to tell them how.

I’m a big fan of trying to make better attacks. Even just looking at site-spoofing scams I’ve been doing this for a couple of decades. Because if we can collectively get ahead of security threats, we’re better able to defend against them.

So no: this isn’t about informing criminals – it’s about understanding what they might do next.

I’d like to highlight four ways that this scam could be made more-effective. Again, this isn’t about helping the criminals: it’s about thinking about and planning for what tomorrow’s attacks might look like.

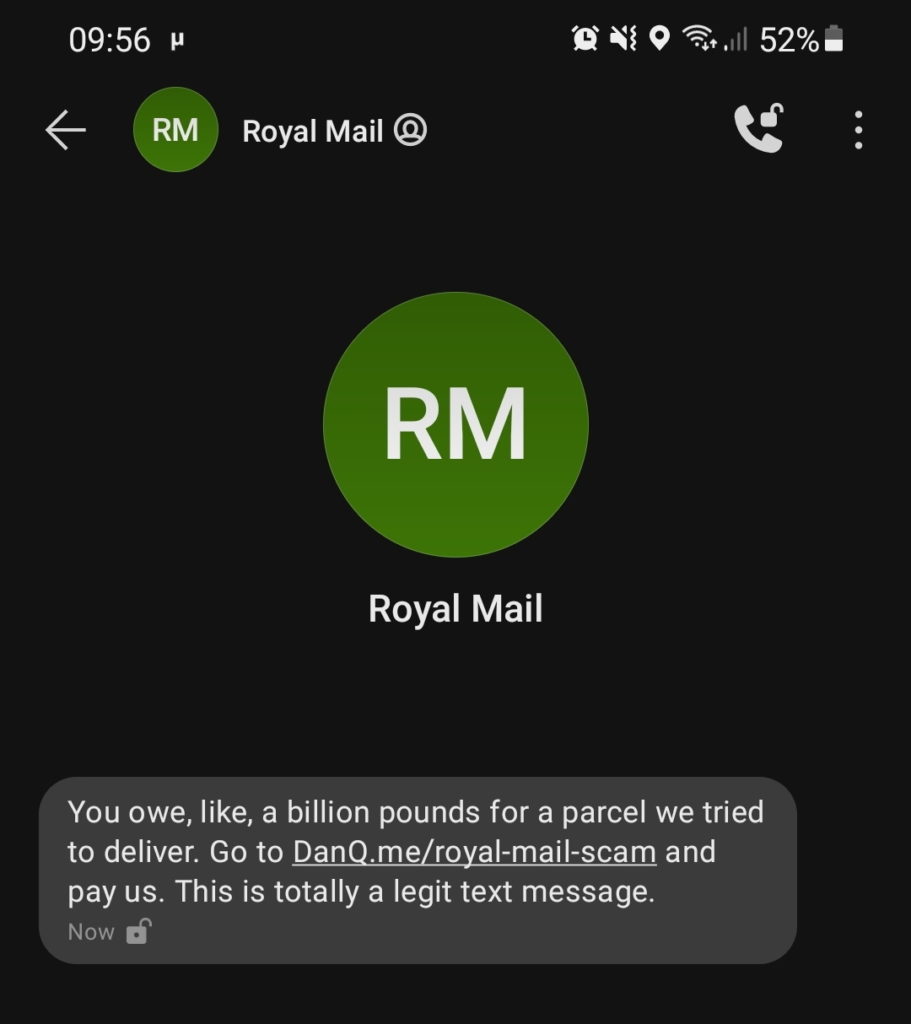

Most of these text messages appear to come from random mobile numbers, which can be an red flag. But it’s distressingly easy to send a text message “from” any other number or even from a short string of text. Imagine how much more-convincing one of these messages would be if it appeared to come from e.g. “Royal Mail” instead?

A further step would be to spoof the message to appear to come from the automated redelivery line of the target courier. Many parcel delivery services have automated lines you can call, provide the code from the card dropped through your door, and arrange redelivery: making the message appear to come from such a number means that any victim who calls it will hear a genuine message from the real company, although they won’t be able to use it because they don’t have a real redelivery card. Plus: any efforts to search for the number online (as is done automatically by scam-detection apps) will likely be confused by the appearance of the legitimate data.

SMS spoofing is getting harder as the underlying industry that supports bulk senders tries to clean up its image, but it’s still easy enough to be a real (yet underexploited) threat.

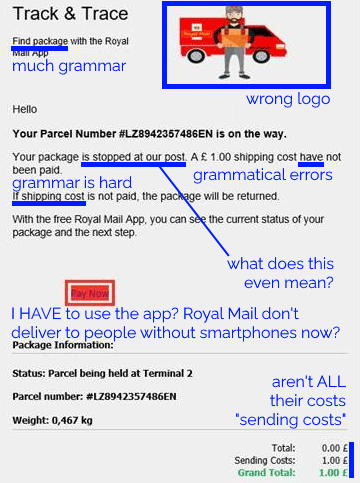

Scammers routinely show a lack of attention to detail that can help give the game away to an attentive target. Spelling and grammar mistakes are commonplace, and compared to legitimate messages the scams generally have suspicious features like providing few options for arranging redelivery or asking for unusual personal information.

They’re getting a lot better at this already: text messages and emails this year are far more-convincing, from an attention-to-detail perspective, than they were three years ago. And because improvements to the scam can be made iteratively, it’s probably already close to the “sweet spot” at the intersection of effort required versus efficacy. But the bad guys’ attention to detail will only grow and in future they’ll develop richer, more-believable designs and content based on whatever success metrics they collect.

On which note: it amazes me that these SMS scams don’t yet seem to include any identifier unique to the victim. Spam

email does this all the time, but a typical parcel scam text directs you to a simple web address like https://royalmail.co.uk.scamsite.com/. A smarter scam could

send you to e.g. https://royalmail.co.uk.scamsite.com/YRC0D35 and/or tell you that your parcel tracking number was e.g. YRC0D35.

Not only would this be more-convincing for anybody who’s familiar with the kind of messages that are legitimately left by couriers, it would also facilitate the gathering of a great deal of additional metrics which scammers could use to improve their operation. For example:

These are exactly the same techniques that legitimate marketers (and email spammers) use to track engagement with emails and advertisements. It stands to reason that any sufficiently-large digital fraud operation could benefit from them too.

I’ve reverse-engineered quite a few parcel scams to work out what they’re recording, and the summary is: not nearly as much as they could be. A typical parcel scam site will ask for your personal details and payment information, and when you submit it will send that information to the attacker. But they could do so much more…

I’ve spoken to potential victims, for example, who got part way through filling the form before it felt suspicious enough that they stopped. Coupled with tracking tokens, even this partial data would have value to a determined fraudster. Suppose the victim only gets as far as typing their name and address… the scammer now has enough information to convincingly call them up, pretending to be the courier, ask for them by name and address, and con them out of their card details over the phone. Every single piece of metadata has value; even just having the victim’s name is a powerful convincer for a future text message campaign.

There’s so much more that parcel fee SMS scammers could be doing to increase the effectiveness of their campaigns, such as the techniques described above. It’s not rocket science, and they’ll definitely have considered them (they won’t learn anything new from this post!)… but if we can start thinking about them it’ll help us prepare to educate people about how to protect themselves tomorrow, as well as today.

This checkin to geohash 2021-06-26 51 -1 reflects a geohashing expedition. See more of Dan's hash logs.

Woodland on Bladon Heath

Thought I’d get up early and cycle up to the hashpoint and back this morning.

Unfortunately I forgot to bring a bike lock, and so when I reached the cycle-inaccessible path across the heath and couldn’t find somewhere to safely leave my bike, I had to give up. Still a nice ride, though.

My GPSr kept a tracklog of the 25km round trip:

This checkin to GC7PEG1 The Cachington Tour reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Managed to answer the questions about the pub, war memorial, and village hall, but the church was locked up tight this morning and I couldn’t find the final clue. :-(

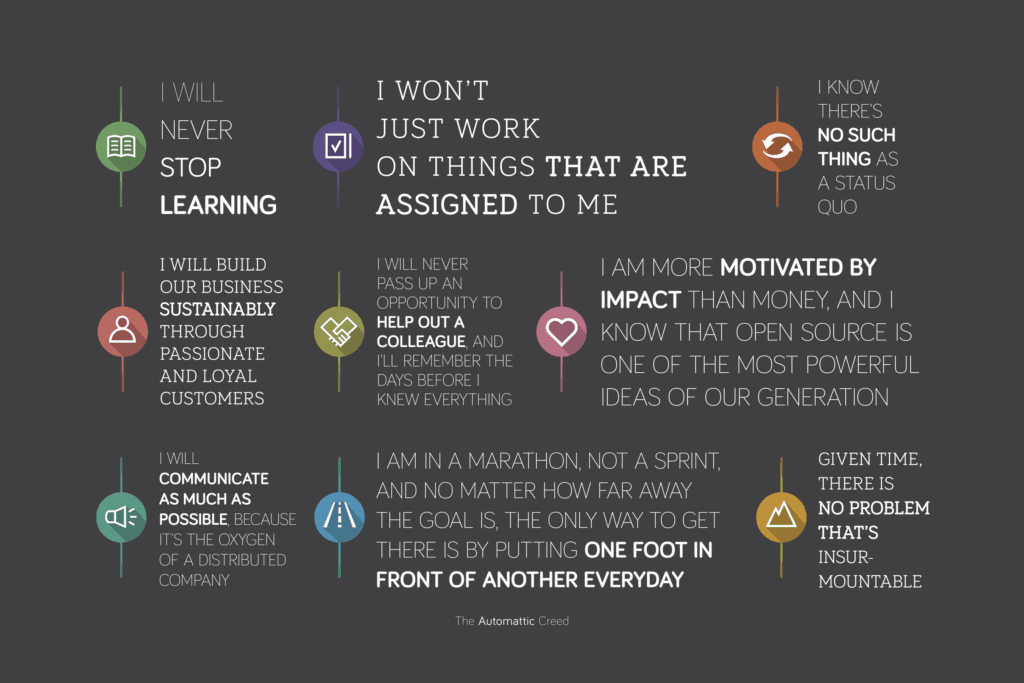

My employer, Automattic, has a creed. Right now it reads:

I will never stop learning. I won’t just work on things that are assigned to me. I know there’s no such thing as a status quo. I will build our business sustainably through passionate and loyal customers. I will never pass up an opportunity to help out a colleague, and I’ll remember the days before I knew everything. I am more motivated by impact than money, and I know that Open Source is one of the most powerful ideas of our generation. I will communicate as much as possible, because it’s the oxygen of a distributed company. I am in a marathon, not a sprint, and no matter how far away the goal is, the only way to get there is by putting one foot in front of another every day. Given time, there is no problem that’s insurmountable.

Lots of companies have something like this, even if it falls short of a “creed”. It could be a “vision”, or a set of “values”, or something in that line.

Of course, sometimes that just means they’ve strung three clichéd words together because they think it looks good under their company logo, and they might as well have picked any equally-meaningless words.

But while most companies (and their staff) might pay lip service to their beliefs, Automattic’s one of few that seems to actually live it. And not in an awkward, shoehorned-in way: people here actually believe this stuff.

By way of example:

We’ve got a bot that, among other things, pairs up people from across the company for virtual “watercooler chat”/”coffee dates”/etc. It’s cool: I pair-up with random colleagues in my division, or the whole company, or fellow queermatticians… and collectively these provide me a half-hour hangout about once a week. It’s a great way to experience the diversity of culture, background and interests of your colleagues, as well as being a useful way to foster idea-sharing and “watercooler effect” serendipity.

For the last six months or so, I’ve been bringing a particular question to almost every random-chat I’ve been paired into:

I volunteer my own answer first. It’s varied over time. Often I’m most-attached to “I will never stop learning.” Other times I connect best to “I will communicate as much as possible…” or “I am in a marathon, not a sprint…”. Lately I’ve felt a particular engagement with “I will never pass up the opportunity to help a colleague…”.

It varies for other people too. But every single person I’ve asked this question has been able to answer it. And they’ve been able to answer it confidently and with justifications for or examples of their choice.

Have you ever worked anywhere before where seemingly all your coworkers profess a genuine belief in the corporate creed? Like, enough that some of them get it tattooed onto their bodies. Unless you’ve been brainwashed by a cult, the answer is probably no.

For some folks, of course, the creed is descriptive rather than prescriptive. Regarding its initial creation, Matt says that “as a hack to introduce new folks to our culture, we put a beta Automattic Creed, basically a statement of things important to us, written in the first person.”

But this alone isn’t an explanation, because back then there were only around a hundred people in the company: nowadays there are over 1,500. So how can the creed continue to be such a pervasive influence? Or to put it another way: why are Automatticians… like that?

I’ve been here 1⅔ years and don’t know the answer yet. But I’ll tell you this: it’s inspiring to be part of a team that really seem to believe in what they do.

Incidentally: if the creed speaks to you too, you might like to look at some of the many open positions! I promise we’re not actually a cult.

Plus we’ve been doing “work anywhere” for longer than almost anybody else and we’re really, really good at it.

If you enjoyed this, you might also like other blog posts about my time with Automattic: the recruitment process, accepting an offer, my induction, and the experience of lockdown in a distributed company, among others.

This checkin to GC8W7QW Forgotten Bridge reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Dropped by while out for a walk and discovered that “Gina + Kylie”, a pair of presumably non-geocachers, found the cache on Tue 8 June and left a note in the logbook! This is cool, not just because it’s always nice to find a friendly muggle but also because it proves that this path isn’t exclusively used by me (and by geocachers following in my footsteps) as I’d thought. Awesome!

Just learned Tuca & Bertie is getting a 2nd season (thanks Adult Swim, no thanks Netflix). Super excited. In anticipation I’m rewatching season 1 of this sort-of “upbeat feminist Bojack Horseman” and (re)loving it.

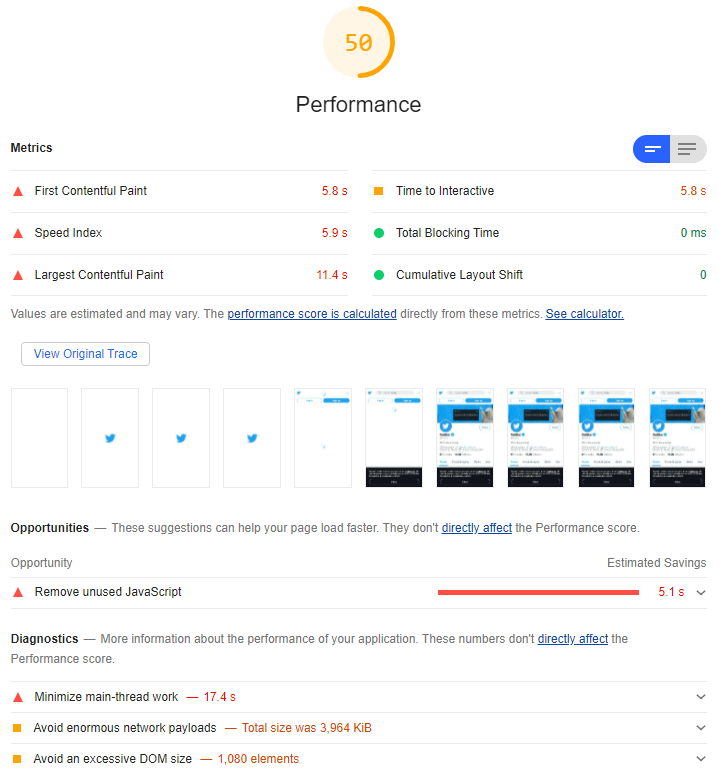

Among Twitter’s growing list of faults over the years are various examples of its increasing divergence from open Web standards and developer-friendly endpoints. Do you remember when you used to be able to subscribe to somebody’s feed by RSS? When you could see who follows somebody without first logging in? When they were still committed to progressive enhancement and didn’t make your browser download ~5MB of Javascript or else not show any content whatsoever? Feels like a long time ago, now.

But those complaints aside, the thing that bugged me most this week was how much harder they’ve made it to programatically get access to things that are publicly accessible via web pages. Like avatars, for example!

If you’re a human and you want to see the avatar image associated with a given username, you can go to twitter.com/that-username and – after you’ve waited

a bit for all of the mandatory JavaScript to download and run (I hope you’re not on a metered connection!) – you’ll see a picture of the user, assuming they’ve uploaded one and not made

their profile private. Easy.

If you’re a computer and you want to get the avatar image, it used to be just as easy; just go to

twitter.com/api/users/profile_image/that-username and you’d get the image. This was great if you wanted to e.g. show a Facebook-style facepile of images of people who’d retweeted your content.

But then Twitter removed that endpoint and required that computers log in to Twitter, so a clever developer made

a service that fetched avatars for you if you went to e.g. twivatar.glitch.com/that-username.

But then Twitter killed that, too. Because despite what they claimed 5½ years ago, Twitter still clearly hates developers.

Recently, I needed a one-off program to get the avatars associated with a few dozen Twitter usernames.

First, I tried the easy way: find a service that does the work for me. I’d used avatars.io before but it’s died, presumably because (as I soon discovered) Twitter had made

things unnecessarily hard for them.

Second, I started looking at the Twitter API documentation but it took me in the region of 30-60 seconds before I said “fuck that noise” and decided that the set-up overhead in doing things the official way simply wasn’t justified for my simple use case.

So I decided to just screen-scrape around the problem. If a human can just go to the web page and see the image, a computer pretending to be a human can do exactly the same. Let’s do this:

/* Copyright (c) 2021 Dan Q; released under the MIT License. */ const Puppeteer = require('puppeteer'); getAvatar = async (twitterUsername) => { const browser = await Puppeteer.launch({args: ['--no-sandbox', '--disable-setuid-sandbox']}); const page = await browser.newPage(); await page.goto(`https://twitter.com/${twitterUsername}`); await page.waitForSelector('a[href$="/photo"] img[src]'); const url = await page.evaluate(()=>document.querySelector('a[href$="/photo"] img').src); await browser.close(); console.log(`${twitterUsername}: ${url}`); }; process.argv.slice(2).forEach( twitterUsername => getAvatar( twitterUsername.toLowerCase() ) );

Obviously, using this code would violate Twitter’s terms of use for automation, so… don’t, I guess?

Given that I only needed to run it once, on a finite list of accounts, I maintain that my approach was probably kinder on their servers than just manually going to every page and saving the avatar from it. But if you set up a service that uses this approach then you’ll certainly piss off somebody at Twitter and history shows that they’ll take their displeasure out on you without warning.

$ node get-twitter-avatar.js alexsdutton richove geohashing TailsteakAD LilFierce1 ninjanails

alexsdutton: https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/740505937039986688/F9gUV0eK_200x200.jpg

lilfierce1: https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/1189417235313561600/AZ2eLjAg_200x200.jpg

richove: https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/1576438972/2011_My_picture4_200x200.jpeg

geohashing: https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/877137707939581952/POzWWV2d_200x200.jpg

ninjanails: https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/1146364466801577985/TvCfb49a_200x200.jpg

tailsteakad: https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/1118738807019278337/y5WWkLbF_200x200.jpg

But it works. It was fast and easy and I got what I was looking for.

And the moral of the story is: if you make an API and it’s terrible, don’t be surprised if people screen-scape your service instead. (You can’t spell “scraping” without “API”, amirite?)

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I have this exact same ride-on mower, but mine doesn’t do this. I feel cheated.