…

If you read a lot of the “how to start a blog in 2023” type posts (please don’t ever use that title in a post) the advice will often boil down to something like:

- Choose a niche

- Start collecting email addresses immediately (newsletter)

- Write on a regular schedule

I don’t do any of those things. 😂

…

Kev writes about what he’s learned from ten years of blogging. As a fellow long-term blogger1, I was especially pleased with his observation that, for some (many?) of us old hands, all the tips on starting a blog nowadays are things that we just don’t do, sometimes deliberately.

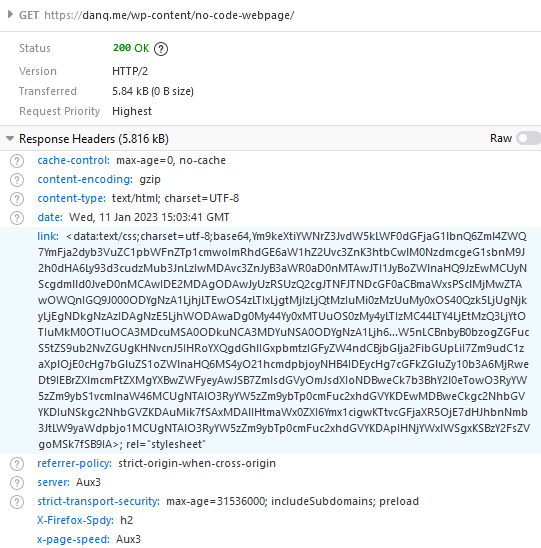

Like Kev, I don’t have a “niche” (I write about the Web, life, geo*ing, technology, childwrangling, gaming, work…). I’ve experimented with email subscription but only as a convenience to people who prefer to get updates that way – the same reason I push articles to Facebook – and it certainly didn’t take off (and that’s fine!). And as for writing on a regular schedule? Hah! I don’t even manage to be uniform throughout the year, even after averaging over my blog’s quarter-century2 of history.

Also like Kev, and I think this is the reason that we ignore these kinds of guides to blogging, I blog for me first and foremost. Creation is a good thing, and I take my “permission to write” and just create stuff. Not having a “niche” means that I can write about what interests me, variable as that is. In my opinion the only guide to starting a blog that anybody needs to read is Andrew Stephens‘ “So You Want To Start An Unpopular Blog”.

And if that’s not enough inspiration for you to jump back in your time machine and party like the Web’s still in 2005, I don’t know what is.

Footnotes

1 I celebrated 20 years… a while back?

2 Fuck me, describing a blog as having about a quarter-century of history makes it sound real old.