The Beeb continue to keep adding more and more non-news content to the BBC News RSS feed (like this ad for the iPlayer app!), so I’ve once again had to update my script to “fix” the feed so that it only contains, y’know, news.

Author: Dan Q

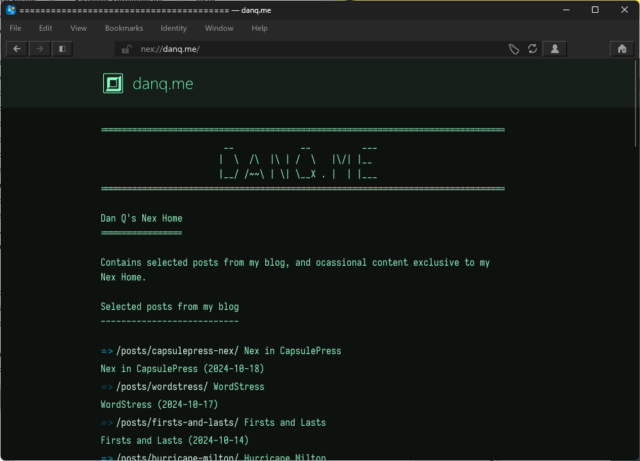

Nex in CapsulePress

I’ve added Nex support to CapsulePress!

What does that mean?

nex://danq.me/ looks in my favourite desktop Gemini/smolweb browser Lagrange.

Nex is a lightweight Internet protocol reminiscent to me of Spartan (which CapsulePress also supports), but even more lightweight. Without even affordances like host identification, MIME types, response codes, or the expectation that Gemtext might be supported by the client, it’s perhaps more like Gopher than it is like Gemini.

It comes from the ever-entertaining smolweb hub of Nightfall City, whose Web interface clearly states at the top of every page the command you could have run to see that content over the Nex protocol. Lagrange added support for Nex almost a year ago and it’s such a lightweight protocol that I was quickly able to adapt CapsulePress’s implementation of Spartan to support Nex, too.

require 'gserver' require 'word_wrap' require 'word_wrap/core_ext' class NexServer < GServer def initialize super( (ENV['NEX_PORT'] ? ENV['NEX_PORT'].to_i : 1900), (ENV['NEX_HOST'] || '0.0.0.0'), (ENV['NEX_MAX_CONNECTIONS'] ? ENV['NEX_MAX_CONNECTIONS'].to_i : 4) ) end def handle(io, req) puts "Nex: handling" io.print "\r\n" req = '/' if req == '' if response = CapsulePress.handle(req, 'nex') io.print response[:body].wrap(79) else io.print "Document not found\r\n" end end def serve(io) puts "Nex: client connected" req = io.gets.strip handle(io, req) end end

Why, you might ask? Well, the reasons are the same as all the other standards supported by CapsulePress:

- The smolweb is awesome.

- Making WordPress into a CMS things it was never meant to do is sorta my jam.

- It was a quick win while I waited for the pharmacist to shoot me up with

5G microchipsmy ‘flu and Covid boosters.

If you want to add Nex onto your CapsulePress, just git pull the latest version, ensure TCP port 1900 isn’t firewalled, and don’t add USE_NEX=false to

your environment. That’s all!

Dan Q wrote note for GC9GTV3 Drive Slowly; Fox Crossing

This checkin to GC9GTV3 Drive Slowly; Fox Crossing reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Checked-in in this cache to ensure it was still healthy, after a recent spate of muggling. Happy to report the cache is well.

Zero

✅ Inbox Zero

✅ Slack Notification Zero

✅ Assigned PR Reviews Zero

✅ Owned PRs… one, but it’s approved and just waiting for the right moment to merge

That’s got the be the first time in… literally years… that I’ve ended a workday so “clean”. Feels amazing.

There’ll be a mess again tomorrow, but hopefully only of a manageable size because I’m particularly clean to finish this week at “Work Zero”.

Note #24744

Happy International Pronouns Day! 🥳

I use he/him pronouns.

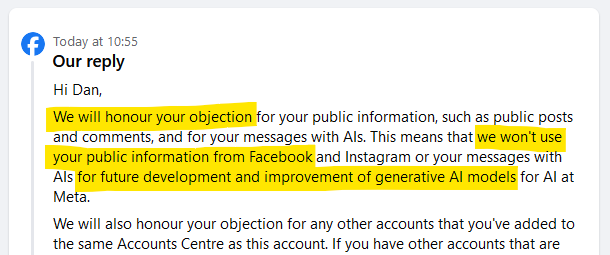

Facebook AI Training Opt-Out

And while we’re talking about AI.

It took a disproportionate about of time to find the right (tiny) link, but eventually I managed to opt-out of my content being used to train Facebook’s AI. They don’t make it easy, do they?

Google turns to nuclear to power AI data centres

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

“The grid needs new electricity sources to support AI technologies,” said Michael Terrell, senior director for energy and climate at Google.

“This agreement helps accelerate a new technology to meet energy needs cleanly and reliably, and unlock the full potential of AI for everyone.”

The deal with Google “is important to accelerate the commercialisation of advanced nuclear energy by demonstrating the technical and market viability of a solution critical to decarbonising power grids,” said Kairos executive Jeff Olson.

…

Sigh.

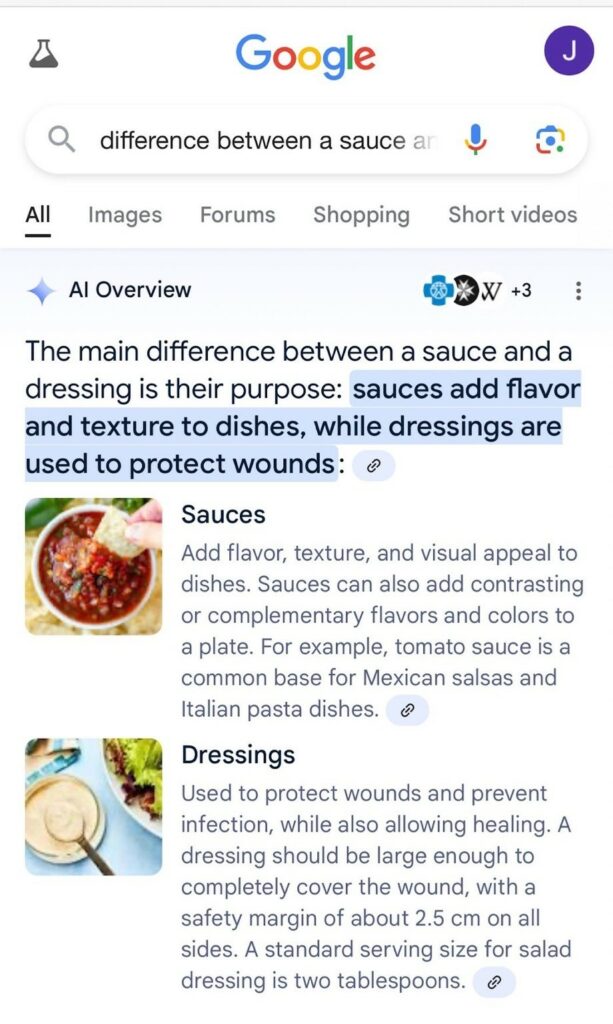

First, something lighthearted-if-it-wasn’t-sad. Google’s AI is, of course, the thing that comes up with gems like this:

Western nations have, in general, been under-investing in new nuclear technologies2, instead continuing to operate ageing second-generation reactors for longer and longer timescales3 while flip-flopping over whether or not to construct a new fleet. It sickens me to say so, but if investment by tech companies is what’s needed to unlock the next-generation power plants, and those plants can keep running after LLMs have had its day and go back to being a primarily academic consideration… then that’s fine by me.

Of course, it’s easy to also find plenty of much more-pessimistic viewpoints too. The other week, I had a dream in which we determined the most-likely identity of the “great filter”: a hypothetical resolution to the Fermi paradox that posits that the reason we don’t see evidence of extraterrestrial life is because there’s some common barrier to the development of spacefaring civilisations that most fail to pass. In the dream, we decided that the most-likely cause was energy hunger: that over time, an advancing civilisation would inevitably develop an increasingly energy-hungry series of egoistic technologies (cryptocurrencies, LLMs, whatever comes next…) and, fuelled by the selfish, individualistic forces that ironically allowed them to compete and evolve to this point, destroy their habitat and/or their sources of power and collapsing. I woke from the dream thinking that there’d be a potential short story to be written there, from the perspective of some future human looking back on the path of the technologies that lead them to whatever technology ultimately lead to our energy-hunger downfall, but never got around to writing it.

I think I’ll try to keep a hold of the optimistic viewpoint, for now: that the snake-that-eats-its-own-tail that is contemporary AI will fizzle out of mainstream relevance, but not before big tech makes big investments in next-generation nuclear, renewable, and energy storage technologies. That’d be nice.

Footnotes

1 Hilari-saddening: when you laugh at something until you realise quite how sad it is.

2 I’m a big fan of nuclear power – as I believe that all informed environmentalists should be – as both a stop-gap to decarbonising energy production and potentially as a relatively-clean long-term solution for balancing grids.

3 Consider for example Hartlepool Nuclear Power Station, which supplies 2%-3% of the UK’s electricity. Construction began in the 1960s and was supposed to run until 2007. Which was extended to 2014 (by which point it was clearly showing signs of ageing). Which was extended to 2019. Which was extended to 2024. It’s still running. The site’s approved for a new reactor but construction will probably be a decade-long project and hasn’t started, sooo…

Note #24735

eBay Balance

eBay UK have changed their terms to (a) remove seller fees for most private sellers, but (b) instead of paying-out immediately, payouts are four times a year (or on-demand).

That sounds like they’re trying to keep money in their ecosystem. The hope is, I guess, that by paying sellers in virtual “eBay Pounds” rather than actual money in the first instance they’ll encourage those sellers to become buyers again (either of other listings, or of eBay’s postage and other services). You can cash out anytime you like, but you can never leave.

You see the same technique used e.g. by the National Lottery, who pay out “small” winnings into your online account, knowing that the vast majority of winnings are on the order of only a few times more than the value of a ticket, and so players will be more-likely to “re-invest” if they’re not paid-out directly.

Or maybe I’m just being cynical.

Sick words

This evening I pushed against my illness-addled brain to try to sit in on the fortnightly Zoom call with the Three Rings dev team. Unfortunately it seems like the primary symptom of my cold is an inability to string words together.

At one point, I apologised to by colleague “Beff” (I meant “Bev”, but I had just been talking about “Geoff”) that I couldn’t work out how to stop “scaring my screen” (well, I suppose Halloween is coming up…). Then, realising my mistake, explained that it was a bit of a “ting-twister”.

I should just go to bed, right?

Firsts and Lasts

Podcast Version

This post is also available as a podcast. Listen here, download for later, or subscribe wherever you consume podcasts.

A lot of attention is paid, often in retrospect, to the experience of the first times in our lives. The first laugh; the first kiss; the first day at your job1. But for every first, there must inevitably be a last.

I recall a moment when I was… perhaps the age our eldest child is now. As I listened to the bats in our garden, my mother told me about how she couldn’t hear them as clearly as she could when she was my age. The human ear isn’t well-equipped to hear that frequency that bats use, and while children can often pick out the sounds, the ability tends to fade with age.

This recollection came as I stayed up late the other month to watch the Perseids. I lay in the hammock in our garden under a fabulously clear sky as the sun finished setting, and – after being still and quiet for a time – realised that the local bat colony were out foraging for insects. They flew around and very close to me, and it occurred to me that I couldn’t hear them at all.

There must necessarily have been a “last time” that I heard a bat’s echolocation. I remember a time about ten years ago, at the first house in Oxford of Ruth, JTA and I (along with Paul), standing in the back garden and listening to those high-pitched chirps. But I can’t tell you when the very last time was. At the time it will have felt unremarkable rather than noteworthy.

First times can often be identified contemporaneously. For example: I was able to acknowledge my first time on a looping rollercoaster at the time.

I wonder what it would be like if we had the same level of consciousness of last times as we did of firsts. How differently might we treat a final phone call to a loved one or the ultimate visit to a special place if we knew, at the time, that there would be no more?

Would such a world be more-comforting, providing closure at every turn? Or would it lead to a paralytic anticipatory grief: “I can’t visit my friend; what if I find out that it’s the last time?”

Footnotes

1 While watching a wooden train toy jiggle down a length of string, reportedly; Sarah Titlow, behind the school outbuilding, circa 1988; and five years ago this week, respectively.

2 Can’t see the loop? It’s inside the tower. A clever bit of design conceals the inversion from outside the ride; also the track later re-enters the fort (on the left of the photo) to “thread the needle” through the centre of the loop. When they were running three trains (two in motion at once) at the proper cadence, it was quite impressive as you’d loop around while a second train went through the middle, and then go through the middle while a third train did the loop!

3 I’m told that the “tower” caught fire during disassembly and was destroyed.

London Transport 25

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Girl on the Net is a popular sex blogger, so this is a link to a SFW page on an otherwise NSFW site. If your only concern is seeing or hearing sexy things or somebody looking over your shoulder and thinking that’s what you’re doing, go ahead and read it. But if you’re connected through the monitored corporate firewall of a sex-negative employer, you might want to read on a different device…

25 different forms of London transport in a day

Hello! My name is Sarah and I love London transport. Because I am a very cool and interesting person, for a long time I’ve thought it might be fun to see how many different types of London transport I can take in a 24-hour period: bus, tram, tube, train, ferry, etc. The trip outlined below took me (and the lucky man I invited on this date) on 25 different forms of London transport in one single day. It criss-crossed the city from East through North to West, then South, Central, South East and back to where we started. I’m sharing the itinerary because this turned out to be a phenomenal adventure, and I thought others might like to give it a go.

…

The rules

The rules for the challenge were:

- Transport must be transport, not a ride, i.e. it must take me from A to B. So the London Eye doesn’t count, but the cable car definitely does.

- Each form of transport must continue the journey. So no going from A to B then immediately back again. The journey can meander, but it must keep moving forwards.

- No form of transport can be taken more than once. Changes on a single line are OK (for instance, if traveling on the DLR from Greenwich to Bank requires a change at Canary Wharf, that’s fine, or if you’re on a bus that gets taken out of service you can get on the next one) but repeated trips on the same form of transport aren’t allowed (you can’t take one double-decker bus in the morning then another in the afternoon). The exceptions to this are: walking; escalators; stairs. We’ll be using these a lot.

…

This sounds like a ludicrously fun adventure and a great use of a date for anybody who can find an even-remotely similarly-transport-obsessed partner.

The one thing this wonderful post is lacking is a map. Oh, and maybe a GPX file, but that’s a much bigger ask. Really I just want the map, to help me visualise the route. Maybe with the different forms of transport colour-coded or something? Okay, okay, now I’m asking a lot again.

Just go read it, it’s a fun London romp.

Note #24701

Calm after the storm

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Regarding the alignment offer at Automattic that resulted in around 1 of every 12/13-or-so Automatticians being paid to leave, my colleague Rosie writes of her experience of the week of the offer and our subsequent week in Mexico:

…

I never thought about taking the offer, but last week took a toll on all of us. It was a weird and sad week. So the Woo DM worked not only as it usually does, a week to bond with colleagues, have fun and collaborate in person. It was also one hundred times more energizing than it usually is. It had that little taste of “we are here because we believe in this. LFG!!!”. A togetherness that feels special. We could talk, discuss, and share our concerns, opinions, memories and new ideas for the future of Woo and WordPress.

…

That’s a good summary of the week, I feel. It was weird and sad, especially to begin with, but it grew into something that was energising and hopeful. There was, in particular, a certain solidarity, of us being the ones who stayed. It’s great to be reminded that my experience is shared.

Whether or not somebody chose to stay for the same reason as me, or as Rosie, it felt like a bonding experience to be among those who made that same decision. I’m glad we got to have this meetup (even though I’m feeling a bit run-down by a combination of exhaustion, jetlag, and – principally – some kind of stomach bug I’ve contracted somewhere along the way, ugh).