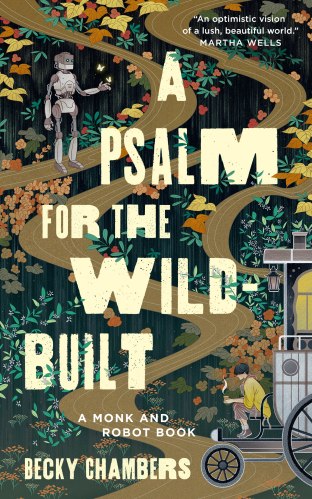

I’d already read every prior book published by the excellent Becky Chambers, but this (and its sequel) had been sitting on my to-read list for some time,

and so while I’ve been ill and off work these last few days, I felt it would be a perfect opportunity to

pick it up. I’ve spent most of this week so far in bed, often drifting in and out of sleep, and a lightweight novella that I coud dip in and out of over the course of a day felt like

the ideal comfort.

I’d already read every prior book published by the excellent Becky Chambers, but this (and its sequel) had been sitting on my to-read list for some time,

and so while I’ve been ill and off work these last few days, I felt it would be a perfect opportunity to

pick it up. I’ve spent most of this week so far in bed, often drifting in and out of sleep, and a lightweight novella that I coud dip in and out of over the course of a day felt like

the ideal comfort.

I couldn’t have been more right, as the very first page gave away. My friend Ash described the experience of reading it (and its sequel) as being “like sitting in a warm bath”, and I see where they’re coming from. True to form, Chambers does a magnificent job of spinning a believable utopia: a world that acts like an idealised future while still being familiar enough for the reader to easily engage with it. The world of Wild-Built is inhabited by humans whose past saw them come together to prevent catastrophic climate change and peacefully move beyond their creation of general-purpose AI, eventually building for themselves a post-scarcity economy based on caring communities living in harmony with their ecosystem.

Writing a story in a utopia has sometimes been seen as challenging, because without anything to strive for, what is there for a protagonist to strive against? But Wild-Built has no such problem. Written throughout with a close personal focus on Sibling Dex, a city monk who decides to uproot their life to travel around the various agrarian lands of their world, a growing philosophical theme emerges: once ones needs have been met, how does one identify with ones purpose? Deprived of the struggle to climb some Maslowian pyramid, how does a person freed of their immediate needs (unless they choose to take unnecessary risks: we hear of hikers who die exploring the uncultivated wilderness Dex’s people leave to nature, for example) define their place in the world?

Aside from Dex, the other major character in the book is Mosscap, a robot whom they meet by a chance encounter on the very edge of human civilisation. Nobody has seen a robot for centuries, since such machines became self-aware and, rather than consign them to slavery, the humans set them free (at which point they vanished to go do their own thing).

To take a diversion from the plot, can I just share for a moment a few lines from an early conversation between Dex and Mosscap, in which I think the level of mutual interpersonal respect shown by the characters mirrors the utopia of the author’s construction:

…

“What—what are you? What is this? Why are you here?”

The robot, again, looked confused. “Do you not know? Do you no longer speak of us?”

“We—I mean, we tell stories about—is robots the right word? Do you call yourself robots or something else?”

“Robot is correct.”

…

“Okay. Mosscap. I’m Dex. Do you have a gender?”

“No.”

“Me neither.”

These two strangers take the time in their initial introduction to ensure they’re using the right terms for one another: starting with those relating to their… let’s say species… and then working towards pronouns (Dex uses they/them, which seems to be widespread and commonplace but far from universal in their society; Mosscap uses it/its, which provides for an entire discussion on the nature of objectship and objectification in self-identity). It’s queer as anything, and a delightful touch.

In any case: the outward presence of the plot revolves around a question that the robot has been charged to find an answer to: “What do humans need?” The narrative theme of self-defined purpose and desires is both a presenting and a subtextual issue, and it carries through every chapter. The entire book is as much a thought experiment as it is a novel, but it doesn’t diminish in the slightest from the delightful adventure that carries it.

Dex and Mosscap go on to explore the world, to learn more about it and about one another, and crucially about themselves and their place in it. It’s charming and wonderful and uplifting and, I suppose, like a warm bath: comfortable and calming and centering. And it does an excellent job of setting the stage for the second book in the series, which we’ll get to presently…

Thank you for sharing this review, the premise of the book sounds interesting.