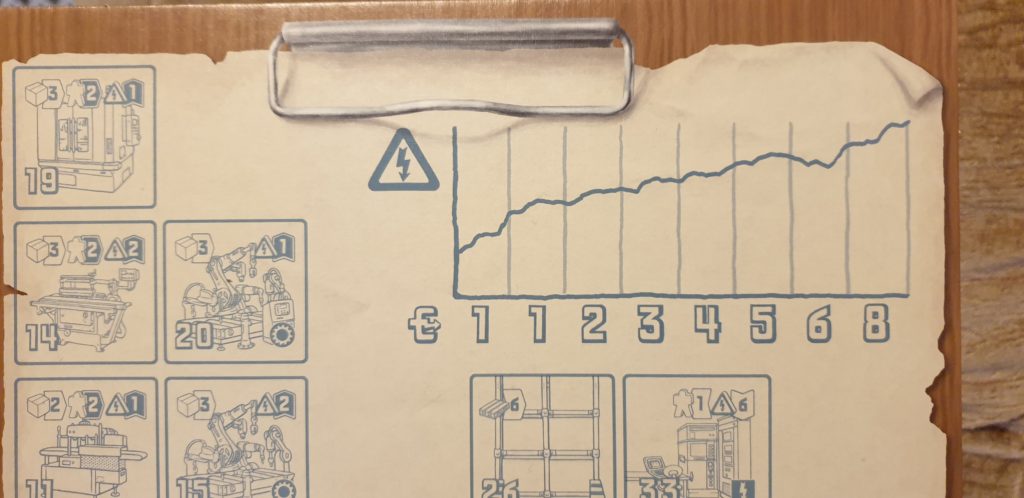

I’m increasingly convinced that Friedemann Friese‘s 2009 board game Power Grid: Factory Manager (BoardGameGeek) presents gamers with a highly-digestible model of the energy economy in a capitalist society. In Factory Manager, players aim to financially-optimise a factory over time, growing production and delivery capacity through upgrades in workflow, space, energy, and staff efficiency. An essential driving factor in the game is that energy costs will rise sharply throughout. Although it’s not always clear in advance when or by how much, this increase in the cost of energy is always at the forefront of the savvy player’s mind as it’s one of the biggest factors that will ultimately impact their profit.

Given that players aim to optimise for turnover towards the end of the game (and as a secondary goal, for the tie-breaker: at a specific point five rounds after the game begins) and not for business sustainability, the game perhaps-accidentally reasonably-well represents the idea of “flipping” a business for a profit. Like many business-themed games, it favours capitalism… which makes sense – money is an obvious and quantifiable way to keep score in a board game! – but it still bears repeating.

There’s one further mechanic in Factory Manager that needs to be understood: a player’s ability to control the order in which they take their turn and their capacity to participate in the equipment auctions that take place at the start of each round is determined by their manpower-efficiency in the previous round. That is: a player who operates a highly-automated factory running on a skeleton staff benefits from being in the strongest position for determining turn order and auctions in their next turn.

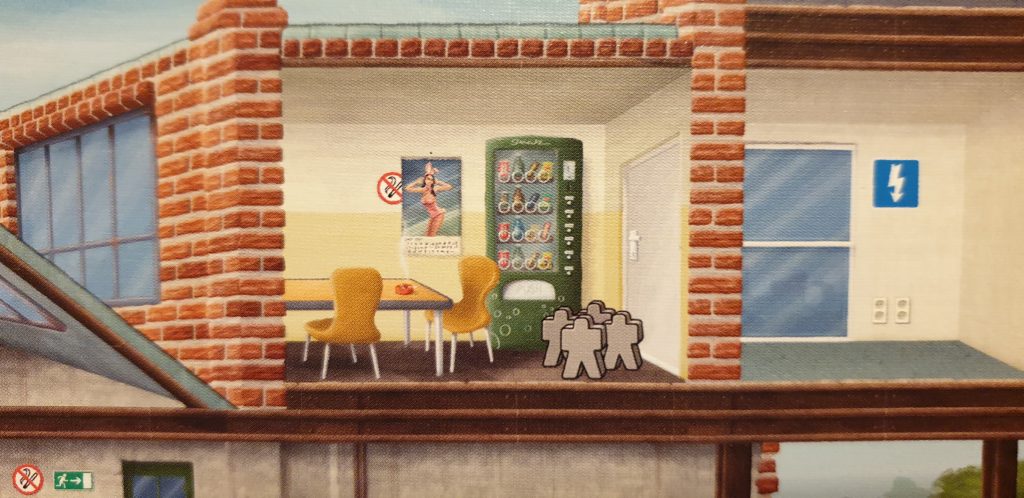

The combination of these rules leads to an interesting twist: in the final turn – when energy costs are at their highest and there’s no benefit to holding-back staff to monopolise the auction phase in the nonexistent subsequent turn – it often makes most sense strategically to play what I call the “sweatshop strategy”. The player switches off the automated production lines to save on the electricity bill, drags in all the seasonal workers they can muster, dusts off the old manpower-inefficient machines mouldering in the basement, and gets their army of workers cranking out widgets!

With indefinitely-increasing energy prices and functionally-flat staff costs, the rules of the game would always eventually reach the point at which it is most cost-effective

to switch to slave cheap labour rather than robots. but Factory Manager‘s fixed-duration means that this point often comes for all players in many games at the same

predictable point: a tipping point at which the free market backslides from automation to human labour to keep itself alive.

There are parallels in the real world. Earlier this month, Tim Watkins wrote:

The demise of the automated car wash may seem trivial next to these former triumphs of homo technologicus but it sits on the same continuum. It is just one of a gathering list of technologies that we used to be able to use, but can no longer express (through market or state spending) a purpose for. More worrying, however, is the direction in which we are willingly going in our collective decision to move from complexity to simplicity. The demise of the automated car wash has not followed a return to the practice of people washing their own cars (or paying the neighbours’ kid to do it). Instead we have more or less happily accepted serfdom (the use of debt and blackmail to force people to work) and slavery (the use of physical harm) as a reasonable means of keeping the cost of cleaning cars to a minimum (similar practices are also keeping the cost of food down in the UK). This, too, is precisely what is expected when the surplus energy available to us declines.

I love Factory Manager, but after reading Watkins’ article, it’ll probably feel a little different to play it, now. It’s like that moment when, while reading the rules, I first poured out the pieces of Puerto Rico. Looking through them, I thought for a moment about what the “colonist” pieces – little brown wooden circles brought to players’ plantations on ships in a volume commensurate with the commercial demand for manpower – represented. And that realisation adds an extra message to the game.

Beneath its (fabulous) gameplay, Factory Manager carries a deeper meaning encouraging the possibility of a discussion about capitalism, environmentalism, energy, and sustainability. And as our society falters in its ability to fulfil the techno-utopian dream, that’s perhaps a discussion we need to be having.

But for now, go watch Sorry to Bother You, where you’ll find further parallels… and at least you’ll get to laugh as you do so.

0 comments