Mr. & Mrs. Simon & Liz G host a party at the end of 2011, inviting their friends from all over the damn place. Video captured by Liz, uploaded by Dan Q.

Mr. & Mrs. Simon & Liz G host a party at the end of 2011, inviting their friends from all over the damn place. Video captured by Liz, uploaded by Dan Q.

In April, my dad’s off to the North Pole, in another of his crazy expeditions! Long-term readers might remember that he and I cycled around Malawi and attempted to canoe down the Caledonian Canal, but his latest adventure makes those two look like a walk in the park!

It’s particularly challenging, I think, because he’s having to walk there. It turns out that there isn’t a regular bus service to the North Pole, which I think pretty-well represents everything that’s wrong with the bus industry these days. I worry about the poor old lady who lives at the North Pole – you know, Santa’s wife – and how she gets out and about when her husband is out in their only flying sleigh.

But in any case, dragging a sled behind yourself which holds everything that you need to survive for over a fortnight on the Arctic ice is a monumental challenge for anybody. As part of his training, my dad’s been dragging a tyre, roped to his waist, around Gateshead. This apparently approximates the amount of drag that is produced by a fully-laden sled, although I’m not sure that the experience is truly authentic as polar bears are significantly less-likely than geordies to mock you for dragging a tyre around. Also less likely to maul you.

In fact, now I think about it, the dangers of Arctic exploration – with its shifting ice, temperatures below -30°C, polar bears, and blizzards – are actually quite tame by comparison to going for a stroll in some parts of Tyneside.

In any case, I’m incredibly proud of what he’s doing. His expedition is self-funded, but he’s also accepting sponsorship to raise money for an organisation called TransAid, who help provide sustainable and safe transport solutions in the developing world, where they can make all the difference to people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to reach a hospital, school, or work opportunities.

So if you’re as impressed as I am with this venture, then please find a little spare change to sponsor this worthy cause: sponsor Peter Huntley’s North Pole trek in aid of TransAid.

I’ve always been enamoured with the concept of urban exploration: that is, the infiltration and examination of abandoned human structures. I was reminded of this recently, when Ruth, JTA and I got the chance to go on an (organised) tour of long-abandoned Aldwych Tube Station in London.

I think for me the appeal comes from the same place as it does when I’m looking around, for example, the ruin of a castle or the wreck of a ship. As opposed to the exploration of the natural world, looking around a man-made thing really gives you the feeling that you’re uncovering the long-lost purpose of the place. This place you are was designed and built to fill a particular need and, for whatever reason, it’s now left to rot and decay. And you – the amateur urban archaeologist, are the link that connects this abandoned world with the present.

I’ve been thinking about some of the places I’ve explored – sewer tunnels underneath what is now Deepdale Retail Park, waterlogged WWII bunkers occupied by squatters, disused railway lines and railyards, roofs of semi-accessible castles, and the (then-disused) wreck that was Aberystwyth’s Alexandra Hall, back when tragically-empty buildings was part of the quirky charm of the place, before they transformed into being a symptom of its downfall. I wanted to share with you a story or two. But instead of any of these, I’ve picked a place that none of you are likely to have heard about:

Wittingham Hospital

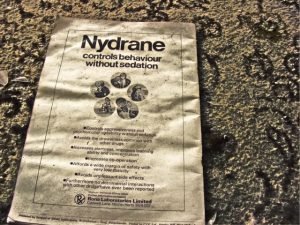

In the mid-19th century, the lunatic asylums of Lancashire and Merseyside were overflowing, and Wittingham Mental Hospital was built to replace them. Originally built to hold 1000 patients, it held over 3,500 by the outbreak of the second world war, making it the largest mental hospital in the country. The mental health reforms of the 1960s (and an inquiry into patient abuse), and new drugs and treatments in the 1970s and 1980s, led to it being gradually emptied and, in 1995, closing for good.

I was still at school when word got around about the closure and a couple of friends and I decided to cycle up to the old hospital and explore it, because there’s nothing like schoolboys egging one another on to give you the courage to “break into the old asylum”. Apparently when I was a kid, I didn’t watch enough horror films about haunted old buildings or about murderous psychopaths, because it seemed like a perfectly reasonable suggestion to me. The council have since put up secure fences and begun demolition, but back then it didn’t take more than a little bit of climbing to gain access to the abandoned complex.

There was a deathly quiet inside the buildings. The distance from the nearest road and the surrounding woodlands muffled the distant sounds of the outside world to less than a whisper, and as the three of us split up and spread out, it was very easy to feel completely alone. The silence was more comforting, though, than eerie: on the hard tile floors and in the big, empty rooms, it’d be impossible to catch anybody unawares, no matter how fleet of foot you might be.

I was surprised to see quite how much furniture and equipment had been simply left: it was almost as if the buildings had been evacuated in a panic, rather than undergoing a controlled, phased closure. Filing cabinets remained, stuffed with papers, in a room with net curtains and a carpet. An upright piano, only slightly out-of-tune, remained in an otherwise empty ward. Beds, operating tables, and cupboards stood exactly as they had when the hospital was still alive.

I couldn’t understand how a place could be abandoned in this way. It’s as if the place itself had died and, instead of being buried, had just been left to decompose in the open air. It seemed – at the least – irresponsible: a friend of mine even came across surgical supplies and syringes, simply left in a cupboard… but more than that, it seemed disrespectful to the building to leave it responsible for looking after these memories of its old self: things which no longer have any purpose, of which it was the custodian, unwilling and unthanked.

We didn’t take any photos – I’m not sure that any of us owned a camera, back then – and we didn’t liberate any of the paperwork (tempting though it was). I’m pretty sure that not one of the three felt that our parents would have approved of us illicitly gaining access to a disused medical facility, so any evidence of our presence was to be avoided! But there was more than that at stake: spending an hour or two wandering around these forgotten corridors, I felt more like a ghost than like a person. We crept about in silence, not saying a word to one another until we’d all reached perimeter once more. It wasn’t our place to interact with this building: all we were there to do was to observe, impotently: to see the beginning of its long decay, that’s since been documented by so many others. That was enough.

I’ll tell you what, though: that early experience? I totally hold it responsible for my subsequent interest in abandoned places.

This link was originally posted to /r/birding. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: https://www.aber.ac.uk/en/news/archive/2011/12/title-110460-en.html

Birds that sing their songs at a higher pitch help them travel further in built-up areas.

Previously it was thought that great tits and other common birds sung at a higher pitch in noisy areas to avoid the low pitch noise from traffic and industry.

Now, scientists from Aberystwyth University and the University of Copenhagen have found that it is the buildings that are changing the way that birds sing in cities.

Their new study, published in the journal PLoS One, suggests that urban architecture may be just as important as background noise in shaping how our birds sing.

“Our cities are packed with reflective surfaces, open spaces and narrow channels, which you just don’t get in woodland. Because sounds bounce and travel in different ways, birds have to use songs that can cope with this”, says researcher Emily Mockford. “The higher notes mean the echoes disappear faster and the next note is clearer”.

A surprise result also showed that urban songs transmitted more clearly in woodland than the rural songs of the local birds. So why don’t rural birds also sing urban songs?

Dr Rupert Marshall, Lecturer in Animal Behaviour at Aberystwyth University, commented “In woodland where trees and leaves obscure the view, many species of songbird can tell how far away a rival is by how degraded its song is. In cities there are fewer visual obstacles and song doesn’t degrade as quickly, so city birds may just concentrate on being heard”.

City birdsong may be bouncing off the walls – but does it have the X factor?

This link was originally posted to /r/vertical. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: http://i.imgur.com/aqWhA.jpg

This self-post was originally posted to /r/OxfordBrookes. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

There’s a list of UK subreddits, including a sub-list of Universities, at: http://www.reddit.com/r/raerth/comments/cwtow/brittit_british_and_anglocentric_subreddits/ – might want to get yourself added to that…

This link was originally posted to /r/technology. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: http://www.computeractive.co.uk/pcw/pc-help/1925325/the-invented-gui

The IBM PC is not alone in having a significant anniversary this year. It is 25 years since Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniac started flogging Apple 1 circuit boards from a Palo Alto garage. But it was not until 1984 that the first Apple Mac made its appearance, with its revolutionary mouse-driven graphical user interface (GUI).

Apple’s achievement in recognising the potential of the GUI and putting it into a mass-market machine cannot be denied. But Apple did not invent the system, as many still believe.

The basic elements of both the MacOS and Windows were developed at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Centre. Xerox did not patent them and blithely showed them off to Jobs, who promptly snaffled the lot.

The roots of the system go back still further. Every computer history website will tell you that Doug Englebart, hired by the US Defense Department to find new ways of harnessing the computer, invented the mouse in 1963.

But this is true only up to a point. Englebart’s contribution was important, but his ideas didn’t come out of the blue.

Roots in radar

Like the pulse circuits that provide the heartbeat of computing, the GUI has its roots in early radar systems. It was wartime radar work that got Englebart thinking about dynamic information displays, and radar engineers were the first to encounter the problem of how to use these displays to communicate with an intelligent machine.

Two engineers came up with a trackball, the innards of the mouse, a full 11 years before Englebart unveiled his device. Moreover, it was used to select a position on a screen to convey information to a processor, which is the fundamental operation of a GUI. One of the engineers, 80-year-old Tom Cranston, is still alive and living in Scotland.

Cranston’s early career nicely mirrors the shift the electronics industry went through in the 1940s and 1950s. Pre-war electronics was overwhelmingly analog, using thermionic valves as amplifiers, oscillators and detectors.

Cranston, who was born in Canada, spent World War II in Britain maintaining Air Force analog radio equipment.

After the war he took an electronics-focused engineering physics degree at the University of Toronto, before joining Ferranti Canada at a time when it was trying to gain a foothold in the nascent computer industry.

This used valves predominantly in switch mode for logic circuits. “What I studied in electronic circuits at university had nothing to do with what was set before us at Ferranti,” he said.

The Datar system – starting from scratch

Cranston was project engineer with a team working on a system for the Canadian Navy called Datar, an attempt to marry radar to digital computers which was way ahead of its time when it started in 1949.

Datar enabled a group of ships to share sonar and radar information. Up to 500 objects could be identified and tracked, and each ship saw the whole position plotted relative to its own moving position.

These calculations would be trivial today, but for Datar the logic had to be hard-wired using around 10,000 valves per ship.

Everything had to be done from scratch. The young engineers recruited for the project even had to prove that data could be transmitted by radio – a demonstration (using pulse-code modulation) that finally persuaded the cash-strapped Canadian government to back the scheme. Positional information was stored on a magnetic drum, a precursor of the hard disk.

The demonstration system on Lake Ontario used standard radar displays with a rotating beam that showed the blips of nearby aircraft, and ships; sonar data from notional submarines was simulated. They needed a way for an operator to identify a target blip and to enter its position.

These displays were drawn by conventional analog circuitry: there was no video RAM to play with. An electronic dot cursor could be thrown up during a brief flyback period between screen sweeps; the engineers needed to find a way that the operator could position this cursor smoothly over a target blip and store the co-ordinates.

To Cranston and his colleague Fred Longstaff, this was just another problem to be solved. “It didn’t seem a big thing… there was a tremendous urgency about all this and it is hard to recreate that atmosphere.”

The simplest answer would have been to set the dot’s X and Y deflections separately using two variable resistances, as used in nearly all electronic level controls, and then translate these values into digital co-ordinates.

Cranston and Longstaff came up with a far more elegant solution that used one control instead of two, and delivered the co-ordinates directly.

The wheel thing

Cranston, while on a visit to a naval establishment, had seen someone using a wheel on a stick, like a miniature pedometer, to measure distances on a chart. “We need something like that which works simultaneously in two dimensions,” he said to Longstaff.

Longstaff then came up with the idea of two follower wheels resting at right angles to a ball that was free to roll in any direction. The prototype actually used two pairs of wheels driven by a standard 4in Canadian bowling ball resting on an air bearing, a feature that is simpler to make than it sounds.

“You just mix up some plaster and stick a ball in it when it is beginning to set,” explained Cranston. “Then you let the plaster harden, take the ball out, drill holes into the plaster, and pump air through them. The result is like magic.”

A circle of holes close to the rim of each wheel passed a beam of light to a photo-sensor, which produced a string of countable pulses as the wheel rotated. Counting circuits were well understood by then, Cranston recalls.

One wheel measured upward movement and its opposite registered down, and the count was incremented or decremented accordingly to provide the Y co-ordinate; the other pair worked similarly to get the X co-ordinate.

Shutters blocked light from the two wheels’ measuring movements opposite to the current rotation. A button – the equivalent of a mouse click – was pressed to indicate a target.

Now and then

Through today’s eyes, this arrangement seems over-elaborate: why not use two wheels and a direction flag? Half a century later, Cranston cannot recall the details of why it was done in this way, but it seems to have been a matter of using what was at hand. Nowadays, a single line of code could cope with the changing directions; the Datar team had to hard-wire everything.

Also routine now is the control of screen positions by numbers, but it was new and intriguing to Cranston and Longstaff. An analog control would have a unique position for each screen co-ordinate, but there was no such direct relationship in the case of the trackball: if you moved the cursor by altering the stored number, the ball would still work regardless of its orientation.

They thought of the device as “centreless” and Longstaff jokingly referred to it as the “turbo-encabulator”.

The whole exercise was what in today’s jargon would be called a proof of concept. The team had to show Datar could work in order to raise the money to refine it, and it needed a lot of money. Valves were unreliable and not really suitable for use on a ship, so the whole system would eventually need rebuilding round new-fangled transistors.

Canada could not afford to do this itself and was seeking a partnership with another country. A system was demonstrated to a succession of military and technical decision makers. One US military observer was so astonished by the sophisticated display that he peered under a table to ensure there was no tomfoolery going on.

Nobody bought into the system. Britain and the US, the most likely partners, had their own projects and there was probably a “not invented here” factor.

Ironically, a prototype US system that Cranston saw later at MIT didn’t need a trackball because it was more advanced: targets were identified and tracked automatically.

Research unrewarded

Many people, though, had seen the trackball. The question of patenting it never arose. Ferranti UK, the parent company, had limited contact with its Canadian arm. Executives had little idea of what was going on at the research level.

Cranston said: “Think about the state of play in the computer world in 1952. There were only a handful of operating computers in the world. Almost all were unreliable. There was no common software language… pulse rates were only 50-100kHz. The idea of using a ball to control a cursor which could intervene and change program execution was a million miles ahead.”

Ball resolvers were not new. They had appeared in navigational and ballistic control mechanisms. The achievement of Longstaff and Cranston was to see how one could be used in conjunction with an electronic display. It was, Cranston says, a generation before its time.

Where Datar went

The Datar experience went into a programmable computer called the FP-6000 which was launched in 1961 by Ferranti Packard – the original company merged in 1958 with Packard Electric.

The FP-6000 was one of the first to use an operating system and was ahead of IBM rivals in its ability to multi-task. Its chief architect was Longstaff. He ended his career as a comms guru with Motorola and died five years ago.

The FP-6000 ended up with ICL, after being bought by Britain’s International Computers and Tabulators, and the two UK firms sold 3000 of them worldwide as the 1900 series.

Cranston left Ferranti in 1956 to take what he describes as a “giant leap backwards”. He joined the Canadian arm of a US company making data loggers and alarm scanners for the Canadian power industry that used logic in the form of mechanical switch arrays.

Electronic computers were considered too unreliable and too expensive for the task. Telephone relay logic filled the gap for another decade.

In fact, Intel’s seminal 4004 was designed originally for tasks like this.

Cranston left after 11 years and moved near to Inverness with his Scottish wife, setting up home in an old mill that he converted himself. He taught for several years in the local technical college, introducing students to the mysteries of the microprocessor.

Surprisingly, Cranston does not have a computer. “They are too fascinating,” he said. “I’d get so involved, I wouldn’t have time for anything else.”

Last week, I wrote about two of the big-name video games I’ve been playing since I suddenly discovered a window of free time in my life, again. Today, I’d like to tell you about some of the smaller independent titles that have captured my interest:

Minecraft

I’d love to be able to say that I was playing Minecraft before it was cool, and I have been playing it since Infdev, which came before the Alpha version. But Minecraft was always cool.

Suppose you’ve been living on another planet all year and so you haven’t heard of Minecraft. Here’s what you need to know: it’s a game, and it’s also a software toy, depending on how you choose to play it. Assuming you’re not playing in “creative mode” (which is a whole other story), then it’s a first-person game of exploration, resource gathering and management, construction, combat, and (if you’re paying multiplayer, which is completely optional) cooperation.

Your character is plunged at dawn into a landscape of rolling (well, stepped) hills, oceans, tundra, and deserts, with infinite blocks extending in every direction. It’s a reasonably safe place during the daytime, but at night zombies and skeletons and giant spiders roam the land, so your first task is to build a shelter. Wood or earth are common starting materials; stone if you’ve got time to start a mine; bricks later on if you’ve got clay close to hand; but seriously: you go build your house out of anything you’d like. Then begins your adventure: explore, mine, and find resources with which to build better tools, and unlock the mysteries of the world (and the worlds beyond). And if you get stuck, just remember that Minecraft backwards is the same as Skyrim forwards.

Parts of it remind me of NetHack, which is one of the computer games that consumed my life: the open world, the randomly-generated terrain, and the scope of the experience put me in mind of this classic Rougelike. Also perhaps Dwarf Fortress or Dungeon Keeper: there’s plenty of opportunities for mining, construction, trap-making, and defensive structures, as well as for subterranean exploration. There are obvious similarities to Terraria, too.

I think that there’s something for everybody in Minecraft, although the learning curve might be steeper than some players are used to.

Limbo

I first heard about Limbo when it appeared on the XBox last year, because it got a lot of press at the time for it’s dark stylistic imagery and “trial and death” style. But, of course, the developers had done a deal with the devil and made it an XBox-only release to begin with, putting off the versions for other consoles and desktop computers until 2011.

But now it’s out, as Paul was keen to advise me, and it’s awesome. You’ll die – a lot – when you play it, but the game auto-saves quietly at very-frequent strategic points, so it’s easy to “just keep playing” (a little like the equally-fabulous Super Meat Boy), but the real charm in this game comes from the sharp contrast between the light, simple platformer interface and the dark, oppressive environment of the levels. Truly, it’s the stuff that nightmares are made of, and it’s beautiful.

While at first it feels a little simplistic (how often nowadays do you get a game whose controls consist of the classic four-button “left”, “right”, “climb/jump”, and “action” options?), the game actually uses these controls to great effect. Sure, you’ll spend a fair amount of time just running to the right, in old-school platformer style, but all the while you’ll be getting drawn in to the shady world of the game, set on-edge by its atmospheric and gloomy soundtrack. And then, suddenly, right when you least expect it: snap!, and you’re dead again.

The puzzles are pretty good: they’re sometimes a little easy, but that’s better in a game like this than ones which might otherwise put you off having “one more go” at a level. There’s a good deal of variety in the puzzle types, stretching the interface as far as it will go. I’ve not quite finished it yet, but I certainly will: it’s a lot of fun, and it’s a nice bit of “lightweight” gaming for those 5-minute gaps between tasks that I seem to find so many of.

I know, I know… as an interactive fiction geek I really should have gotten around to finishing Blue Lacuna sooner. I first played it a few years ago, when it was released, but it was only recently that I found time to pick it up again and play it to, well, it’s logical conclusion.

What do you need to know to enjoy this game? Well: firstly, that it’s free. As in: really free – you don’t have to pay to get it, and anybody can download the complete source code (I’d recommend finishing the game first, because the source code is, of course, spoiler-heavy!) under a Creative Commons license and learn from or adapt it themselves. That’s pretty awesome, and something we don’t see enough of.

Secondly, it’s a text-based adventure. I’ve recommended a few of these before, because I’m a big fan of the medium. This one’s less-challenging for beginners than some that I’ve recommended: it uses an unusual user interface feature that the developer calls Wayfaring, to make it easy and intuitive to dive in. There isn’t an inventory (at least, not in the conventional adventure game sense – although there is one optional exception to this), and most players won’t feel the need to make a map (although keeping notes is advisable!). All-in-all, so far it just sounds like a modern, accessible piece of interactive fiction.

But what makes this particular piece so special is it’s sheer size and scope. The world of the game is nothing short of epic, and more-than almost any text-based game I’ve played before, it feels alive: it’s as much fun to explore the world as it is to advance the story. The “simplified” interface (as described above) initially feels a little limiting to an experienced IFer like myself, but that quickly gives way as you realise how many other factors (other than what you’re carrying) can be used to solve problems. Time of day, tides, weather, who you’ve spoken to and about what, where you’ve been, when you last slept and what you dreamed about… all of these things can be factors in the way that your character experiences the world in Blue Lacuna, and it leads to an incredibly deep experience.

It describes itself as being an explorable story in the tradition of interactive fiction and text adventures… a novel about discovery, loss, and choice.. a game about words and emotions, not guns. And that’s exactly right.

It’s available for MacOS, Windows, Linux, and just about every other platform, and you should totally give it a go.

This self-post was originally posted to /r/ColorBlind. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

I’m not colourblind, and I’m not really a mobile developer, so maybe there’s something I’ve missed, but I’ve got an idea for an app and I thought I’d run it by you guys to see if there’s something I’ve missed.

Mobile processing power is getting better and better, and we’re probably getting close to the point where we can do live video image manipulation at acceptable framerates (even 10 frames/sec would be something). So why can’t we make an app that shifts colours as seen by the camera to a particular different part of the spectrum (depending on the user’s preferences).

For example, a deuteranomat (green weak, difficulty differentiating through the red/orange/yellow/green spectrum) might configure the software to shift yellows and greens to instead be presented as purples and blues. The picture would be false, of course, but it would help distinguish between colours in order to make, for example, colour-coded maps readable.

I was thinking about how video cameras can often “see” infa-red (try pointing a remote control at a video camera and pressing the button), and present it to the viewer as white or red, when I saw a documentary with some footage of “how bees see the world”. Bees have vision of a similar breadth of spectrum to humans, but shifted well into the infa-red range (and away from the blue end of the spectrum). In the documentary, they’d filmed some flowers using a highly infa-red sensitive camera, and then they’d “shifted” the colours around the spectrum in order to make it visible to normal humans: the high-infa-reds became yellows, the low-infa-reds became blues, and the reds they left as reds. Obviously this isn’t what bees actually experience, but it’s an approximation that allows us to appreciate the variety in their spectrum.

Can we make this conversion happen “live” on mobile technology? And why haven’t we done so!

This review originally appeared on Steam. See more reviews by Dan.

Needless to say, I can’t recommend this highly enough. The pinnacle of the series of Civilization games still keeps me coming back time and time again.

This review originally appeared on Steam. See more reviews by Dan.

In an age where platform games are few and far between, and don’t “feel” like platform games ever used to, one game tries to make an exception. And it’s beautiful and fast and stylish.

This review originally appeared on Steam. See more reviews by Dan.

Good clean fun. Warning: addictive!

This review originally appeared on Steam. See more reviews by Dan.

Spectacular, deep, enormous, living world. And I just wanted to explore it, take on epic quests, carve out a legacy as an adventurer.

But then I took an arrow in the knee.

Seriously though: an awesome game. I spent 85+ hours playing it before I got to the end of the main quest line, and there’s still a lot I’d like to go back and do, so it’s one of the best value video games I’ve played in a long while. Go get it.

Well, that was a farce.

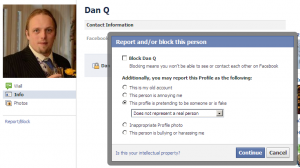

tl;dr: [skip to the end] I’m closing my Facebook account. I’ve got some suggestions at the bottom of this post about how you might like to keep in touch with me in future, if you previously liked to do so via Facebook.

The Backstory

A little over three weeks ago, I was banned from Facebook for having a fake name. This surprised me, because I was using my real name – it’s an unusual name, but it’s mine. I was interested to discover that Claire, who shares my name, hadn’t been similarly banned, so it seems that this wasn’t part of some “sweep” for people with one-letter names, but instead was probably the result of somebody (some stranger, I’d like to hope) clicking the “Report this as a fake name” link on my profile.

There are many, many things about this that are alarming, but the biggest is the “block first; ask questions later” attitude. I wasn’t once emailed to warn me that I would be banned. Hell: I wasn’t even emailed to tell me that I had been banned. It took until I tried to log in before I found out at all.

The Problem

I don’t make much use of Facebook, really. I cross-post my blog posts there, and I keep Pidgin signed in to Facebook Chat in case anybody’s looking for me. Oh, and I stalk people from my past, but that’s just about the only thing I do on it that everybody does on it. I don’t really wallpost, I avoid internal messages (replying to them, where possible, by email), and I certainly don’t play fucking FarmVille.

So what’s the problem? It’s not like I’d be missing anything if I barely use it anyway? The problem is that my account was still there, it’s just that I didn’t have access to it.

That meant that people still invited me to things and sent me messages. My friends are smart enough to know that I won’t see anything they write on their wall, but they assume that if they update the information of a party they’ve Facebook-invited me to that I’ll get it. For example, I was recently at a fabulous party at Gareth and Penny‘s which they organised mostly via Facebook. They’d be forgiven for assuming that when they sent a message to “the guests” – a list that included me – that I would get that message: but no – it fell silently away into Facebook’s black hole.

The Farce(book?)

Following this discovery, here’s how I spent the next three weeks:

Hi Dan,

Thanks for verifying your identity. Note that we permanently deleted your attached ID from our servers.

After investigating this further, it looks like we suspended your account by mistake. I’m so sorry for the inconvenience. You should now be able to log in. If you have any issues getting back into your account, please let me know.

Thanks,

Aoife

User Operations

The Resolution

So now, I’m back on Facebook, and I’ve learned something: having a Facebook account that you can’t log in to is worse than not having a Facebook account at all. If I didn’t have one at all, at least people would know that they couldn’t contact me that way. In my situation, Facebook were effectively lying to my friends: telling them “Yeah, sure: we’ll pass on your message to Dan!” and then not doing so. It’s a little bit like digital identity theft, and it’s at least a little alarming.

I’ve learned something else, too: Facebook can’t be trusted to handle this kind of situation properly. Anybody could end up in my situation. Those of you with unusual (real) names, or unusual-looking pseudonyms, or who use fake names on Facebook (and I know that there are at least a dozen of you on my friends list)… or just those of you whose name looks a little bit off to a Facebook employee… you’re all at risk of this kind of lockout.

Me? I was a little pissed off, but it wasn’t the end of the world. But I know people who use Facebook’s “single sign-on” authentication systems to log in to other services. I know people who do some or all of their business through Facebook. Increasingly, I’ve seen people store their telephone or email address books primarily on Facebook. What do you do when you lose access to this and can’t get it back? When there’s nowhere to appeal?

And that’s how I came to my third lesson: I can’t rely on Facebook not to make this kind of fuck-up again. No explanation was given as to how their “mistake” was made, so I can’t trust that whatever human or automated system was at fault won’t just do the same damn dumb thing tomorrow to me or to somebody I know. And personally, I don’t like Facebook to seize control of my account and to pretend to be me. I come full circle to my first realisation – that it would be better not to have a Facebook account at all than to have one that I can’t access – and realise that because that’s liable to happen again at any time, that I shouldn’t have a Facebook account.

So, I’m ditching Facebook.

None of this pansy “deactivation” shit, either – do you know what that actually does, by the way? It just hides your wall and stops new people from friending you: it still keeps all of your information, because it’s basically a scam to try to keep your data while making you think you’ve left. No, I’m talking about the real “permanent deletion” deal.

I’m going to hang around for a few days to make sure I’ve harvested everybody’s email addresses and pushing this post to my wall and whatnot, and then I’m gone.

If you’re among those folks who aren’t sure how to function outside of Facebook, but still want to keep in touch with me, here’s what you need to know:

Ironically, the only Facebook accounts I’ll have now are the once which do have fake names. Funny how they’re the ones that never seem to get banned.

As I previously indicated, I’ve recently found myself with a little free videogaming time, and I thought I’d share some of the things that have occupied my time, over the course of two blog posts:

Skyrim

Well; here’s the big one. This game eats time for breakfast. It’s like World Of Warcraft for people who don’t have friends. No, wait…

Seriously, though, Bethesda have really kicked arse with this one. I only played a little of the earlier games in the series, because they didn’t “click” with me (although I thoroughly enjoyed the entire Fallout series), but Skyrim goes a whole extra mile. The game world feels truly epic and “living”: you don’t have to squint more than a little to get the illusion that the whole world would carry on without you, with people eating and sleeping and going to work and gossiping about all the dragon attacks. The plot is solid, the engine is beautiful, and there’s so much content that it’s simply impossible to feel that you’re taking it all in at once.

It’s not perfect. It’s been designed with console controls in mind, and it shows (the user interface for skills upgrades is clunky as hell, even when I tried it on my XBox controller). The AI still does some damn stupid things (not standing-and-talking-to-walls stupid, but still bad enough that your so-called “friends” will get in your way, fire area-effect weapons at enemies you’re meleeing with, and so on). Dragons are glitchy (the first time I beat an Elder Dragon it was mostly only because it landed in a river and got its head stuck underwater, like it was seeing how long it could hold it’s breath while I gradually sliced its tail into salami).

But it’s still a huge and beautiful game that’s paid for itself in the 55+ hours of entertainment it’s provided so far. Recommended.

Update: between first drafting and actually publishing this list, I’ve finished the main questline of Skyrim, which was fun. 85 hours and counting.

Modern Warfare 3

I should confess, first, that I’m a Call Of Duty fanboy. Not one of the these modern CoD fanboys, who rack up kills in multiplayer matchups orchestrated by ability-ranking machines in server farms, shouting “noob” as they teabag one another’s corpses. I mean I’m a purist CoD fanboy. When I got my copy of the first Call Of Duty game, broadband was just beginning to take off, and games with both single-player and multiplayer aspects still had to sell themselves on the strength of the single-player aspects, because most of their users would only ever play it that way.

And the Call of Duty series has always had something that’s been rare in action-heavy first-person shooters: a plot. A good plot. A plot that you can actually get behind and care about. Okay, so we all know how the World War II ones end (spoiler: the allies win), and if you’ve seen Enemy At The Gates then you also know how every single Russian mission goes, too, but they’ve still got a fun story and they work hard to get you emotionally-invested. The first time I finished Call of Duty 2, I cried. And then I started over and shot another thousand Nazis, like I was some form of human tank.

Modern Warfare was fantastic, bringing the franchise (complete with Captain Price) right into the era of nuclear threats and international terrorism. Modern Warfare 2 built on this and took it even further, somehow having a final boss fight that surpassed even the excellence of its predecessor (“boss fights” being notoriously difficult to do well in first-person shooters inspired by the real world). Modern Warfare 3… well…

It was okay. As a fanboy, I loved the fact that they finally closed the story arc started by the two previous MW games (and did so in a beautiful way: I maintain that Yuri is my favourite character, simply because of the way his story is woven into the arc). The chemical weapon attacks weren’t quite so impressive as the nuclear bomb in MW2, and the final fight wasn’t quite as good as the previous ones, but they’re all “good enough”. The big disappointment was the length of the campaign. The game finished downloading and unlocked at 11pm, and by 4am I was tucked up in bed, having finished it in a single sitting. “Was that it?” I asked.

Recommendation: play it if you’re a fan and want to see how the story ends, or else wait until it’s on sale and play it then.

Part Two will come when I find time, along with some games that you’re less-likely to have come across already.