What’s the difference between “streaming” and “downloading” video, audio, or some other kind of linear media?1

They’re basically the same thing

Despite what various platforms would have you believe, there’s no significant technical difference between streaming and downloading.

Suppose you’re choosing whether to download or stream a video2. In both cases3:

- The server gets frames of video from a source (file, livestream, etc.)

- The server sends those frames to your device

- Your device stores them while it does something with them

So what’s the difference?

The fundamental difference between streaming and downloading is what your device does with those frames of video:

Does it show them to you once and then throw them away? Or does it re-assemble them all back into a video file and save it into storage?

Buffering is when your streaming player gets some number of frames “ahead” of where you’re watching, to give you some protection against connection issues. If your WiFi wobbles for a moment, the buffer protects you from the video stopping completely for a few seconds.

But for buffering to work, your computer has to retain bits of the video. So in a very real sense, all streaming is downloading! The buffer is the part of the stream that’s downloaded onto your computer right now. The question is: what happens to it next?

All streaming is downloading

So that’s the bottom line: if your computer deletes the frames of video it was storing in the buffer, we call that streaming. If it retains them in a file, we call that downloading.

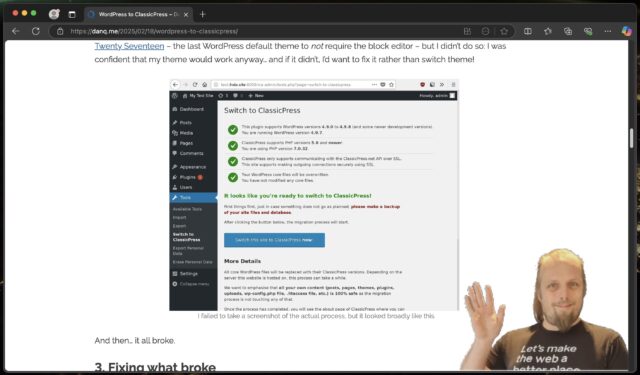

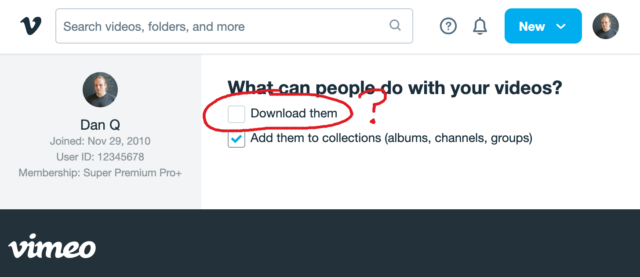

That definition introduces a philosophical problem. Remember that Vimeo checkbox that lets a creator decide whether people can (i.e. are allowed to) download their videos? Isn’t that somewhat meaningless if all streaming is downloading.

Because if the difference between streaming and downloading is whether their device belonging to the person watching the video deletes the media when they’re done. And in virtually all cases, that’s done on the honour system.

When your favourite streaming platform says that it’s only possible to stream, and not download, their media… or when they restrict “downloading” as an option to higher-cost paid plans… they’re relying on the assumption that the user’s device can be trusted to delete the media when the user’s done watching it.

But a user who owns their own device, their own network, their own screen or speakers has many, many opportunities to not fulfil the promise of deleting media it after they’ve consumed it: to retain a “downloaded” copy for their own enjoyment, including:

- Intercepting the media as it passes through their network on the way to its destination device

- Using client software that’s been configured to stream-and-save, rather than steam-and-delete, the content

- Modifying “secure” software (e.g. an official app) so that it retains a saved copy rather than deleting it

- Capturing the stream buffer as it’s cached in device memory or on the device’s hard disk

- Outputting the resulting media to a different device, e.g. using a HDMI capture device, and saving it there

- Exploiting the “analogue4 hole”5: using a camera, microphone, etc. to make a copy of what comes out of the screen/speakers6

Okay, so I oversimplified (before you say “well, actually…”)

It’s not entirely true to say that streaming and downloading are identical, even with the caveat of “…from the server’s perspective”. There are three big exceptions worth thinking about:

Exception #1: downloads can come in any order

When you stream some linear media, you expect the server to send the media in strict chronological order. Being able to start watching before the whole file has downloaded is a big part of what makes steaming appealing, to the end-user. This means that media intended for streaming tends to be stored in a way that facilitates that kind of delivery. For example:

- Media designed for streaming will often be stored in linear chronological order in the file, which impacts what kinds of compression are available.

- Media designed for streaming will generally use formats that put file metadata at the start of the file, so that it gets delivered first.

- Video designed for streaming will often have frequent keyframes so that a client that starts “in the middle” can decode the buffer without downloading too much data.

No such limitation exists for files intended for downloading. If you’re not planning on watching a video until it’s completely downloaded, the order in which the chunks arrives is arbitrary!

But these limitations make the set of “files suitable for streaming” a subset of the set of “files suitable for downloading”. It only makes it challenging or impossible to stream some media intended for downloading… it doesn’t do anything to prevent downloading of media intended for streaming.

Exception #2: streamed media is more-likely to be transcoded

A server that’s streaming media to a client exists in a sort-of dance: the client keeps the server updated on which “part” of the media it cares about, so the server can jump ahead, throttle back, pause sending, etc. and the client’s buffer can be kept filled to the optimal level.

This dance also allows for a dynamic change in quality levels. You’ve probably seen this happen: you’re watching a video on YouTube and suddenly the quality “jumps” to something more (or less) like a pile of LEGO bricks7. That’s the result of your device realising that the rate at which it’s receiving data isn’t well-matched to the connection speed, and asking the server to send a different quality level8.

The server can – and some do! – pre-generate and store all of the different formats, but some servers will convert files (and particularly livestreams) on-the-fly, introducing a few seconds’ delay in order to deliver the format that’s best-suited to the recipient9. That’s not necessary for downloads, where the user will often want the highest-quality version of the media (and if they don’t, they’ll select the quality they want at the outset, before the download begins).

Exception #3: streamed media is more-likely to be encumbered with DRM

And then, of course, there’s DRM.

As streaming digital media has become the default way for many people to consume video and audio content, rights holders have engaged in a fundamentally-doomed10 arms race of implementing copy-protection strategies to attempt to prevent end-users from retaining usable downloaded copies of streamed media.

Take HDCP, for example, which e.g. Netflix use for their 4K streams. To download these streams, your device has to be running some decryption code that only works if it can trace a path to the screen that it’ll be outputting to that also supports HDCP, and both your device and that screen promise that they’re definitely only going to show it and not make it possible to save the video. And then that promise is enforced by Digital Content Protection LLC only granting a decryption key and a license to use it to manufacturers.11

Anyway, the bottom line is that all streaming is, by definition, downloading, and the only significant difference between what people call “streaming” and “downloading” is that when “streaming” there’s an expectation that the recipient will delete, and not retain, a copy of the video. And that’s it.

Footnotes

1 This isn’t the question I expected to be answering. I made the animation in this post for use in a different article, but that one hasn’t come together yet, so I thought I’d write about the technical difference between streaming and downloading as an excuse to use it already, while it still feels fresh.

2 I’m using the example of a video, but this same principle applies to any linear media that you might stream: that could be a video on Netflix, a livestream on Twitch, a meeting in Zoom, a song in Spotify, or a radio show in iPlayer, for example: these are all examples of media streaming… and – as I argue – they’re therefore also all examples of media downloading because streaming and downloading are fundamentally the same thing.

3 There are a few simplifications in the first half of this post: I’ll tackle them later on. For the time being, when I say sweeping words like “every”, just imagine there’s a little footnote that says, “well, actually…”, which will save you from feeling like you have to say so in the comments.

4 Per my style guide, I’m using the British English spelling of “analogue”, rather than the American English “analog” which you’ll often find elsewhere on the Web when talking about the analog hole.

5 The rich history of exploiting the analogue hole spans everything from bootlegging a 1970s Led Zeppelin concert by smuggling recording equipment in inside a wheelchair (definitely, y’know, to help topple the USSR and not just to listen to at home while you get high) to “camming” by bribing your friendly local projectionist to let you set up a video camera at the back of the cinema for their test screening of the new blockbuster. Until some corporation tricks us into installing memory-erasing DRM chips into our brains (hey, there’s a dystopic sci-fi story idea in there somewhere!) the analogue hole will always be exploitable.

6 One might argue that recreating a piece of art from memory, after the fact, is a very-specific and unusual exploitation of the analogue hole: the one that allows us to remember (or “download”) information to our brains rather than letting it “stream” right through. There’s evidence to suggest that people pirated Shakespeare’s plays this way!

7 Of course, if you’re watching The LEGO Movie, what you’re seeing might already look like a pile of LEGO bricks.

8 There are other ways in which the client and server may negotiate, too: for example, what encoding formats are supported by your device.

9 My NAS does live transcoding when Jellyfin streams to devices on my network, and it’s magical!

10 There’s always the analogue hole, remember! Although in practice this isn’t even remotely necessary and most video media gets ripped some-other-way by clever pirate types even where it uses highly-sophisticated DRM strategies, and then ultimately it’s only legitimate users who end up suffering as a result of DRM’s burden. It’s almost as if it’s just, y’know, simply a bad idea in the first place, or something. Who knew?

11 Like all these technologies, HDCP was cracked almost immediately and every subsequent version that’s seen widespread rollout has similarly been broken by clever hacker types. Legitimate, paying users find themselves disadvantaged when their laptop won’t let them use their external monitor to watch a movie, while the bad guys make pirated copies that work fine on anything. I don’t think anybody wins, here.