Prefer to watch/listen than read? There’s a vloggy/video version of this post in which I explain all the key concepts and demonstrate an SHA-1 length extension attack against an imaginary site.

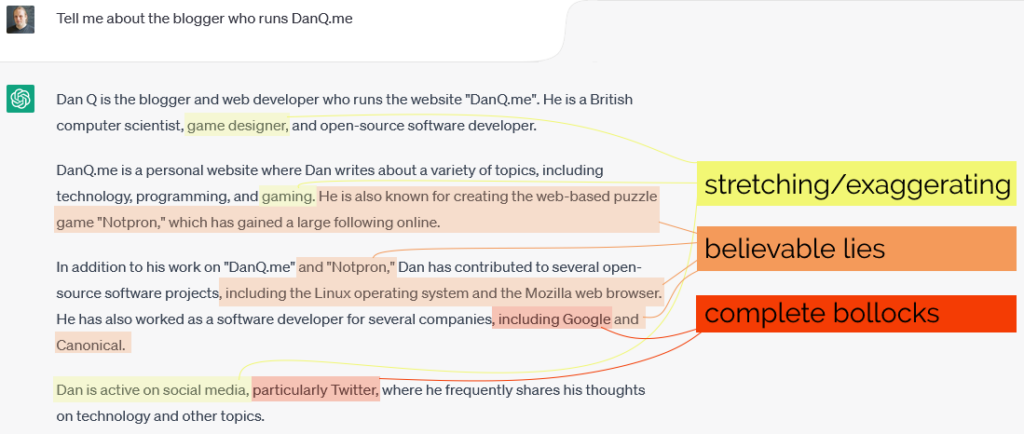

I understood the concept of a length traversal attack and when/how I needed to mitigate them for a long time before I truly understood why they worked. It took until work provided me an opportunity to play with one in practice (plus reading Ron Bowes’ excellent article on the subject) before I really grokked it.

Would you like to learn? I’ve put together a practical demo that you can try for yourself!

You can check out the code and run it using the instructions in the repository if you’d like to play along.

Using hashes as message signatures

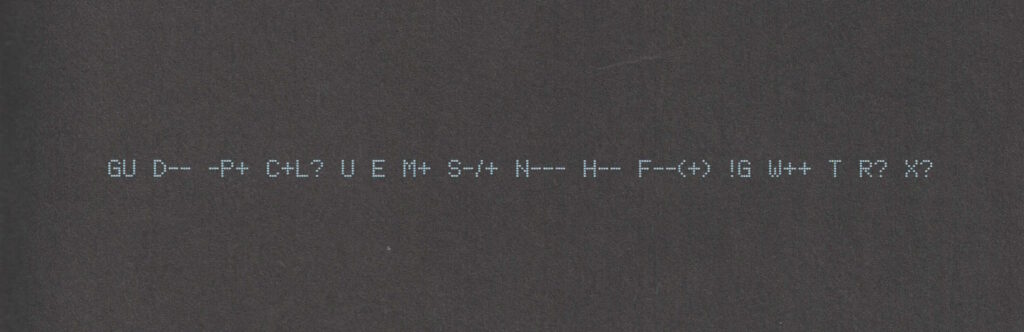

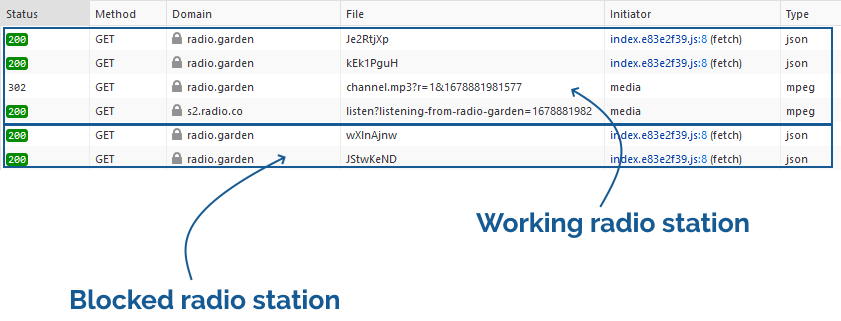

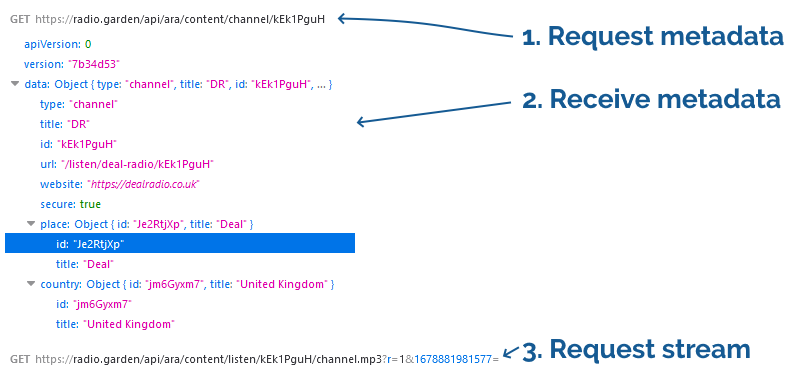

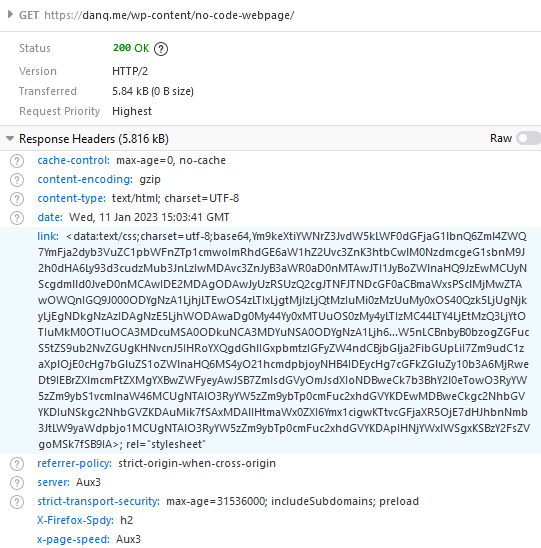

The site “Images R Us” will let you download images you’ve purchased, but not ones you haven’t. Links to the images are protected by a SHA-1 hash1, generated as follows:

When a “download” link is generated for a legitimate user, the algorithm produces a hash which is appended to the link. When the download link is clicked, the same process is followed and the calculated hash compared to the provided hash. If they differ, the input must have been tampered with and the request is rejected.

Without knowing the secret key – stored only on the server – it’s not possible for an attacker to generate a valid hash for URL parameters of the attacker’s choice. Or is it?

download=free to download=valuable invalidates the hash, and the request is denied.

Actually, it is possible for an attacker to manipulate the parameters. To understand how, you must first understand a little about how SHA-1 and its siblings actually work:

SHA-1‘s inner workings

- The message to be hashed (

SECRET_KEY+URL_PARAMS) is cut into blocks of a fixed size.2 - The final block is padded to bring it up to the full size.3

- A series of operations are applied to the first block: the inputs to those operations are (a) the contents of the block itself, including any padding, and (b) an initialisation vector defined by the algorithm.4

- The same series of operations are applied to each subsequent block, but the inputs are (a) the contents of the block itself, as before, and (b) the output of the previous block. Each block is hashed, and the hash forms part of the input for the next.

- The output of running the operations on the final block is the output of the algorithm, i.e. the hash.

In SHA-1, blocks are 512 bits long and the padding is a 1, followed by as many 0s as is necessary,

leaving 64 bits at the end in which to specify how many bits of the block were actually data.

Padding the final block

Looking at the final block in a given message, it’s apparent that there are two pieces of data that could produce exactly the same output for a given function:

- The original data, (which gets padded by the algorithm to make it 64 bytes), and

- A modified version of the data, which has be modified by padding it in advance with the same bytes the algorithm would; this must then be followed by an additional block

Therefore, if we can manipulate the input of the message, and we know the length of the message, we can append to it. Bear that in mind as we move on to the other half of what makes this attack possible.

Parameter overrides

“Images R Us” is implemented in PHP. In common with most server-side scripting languages, when PHP sees a HTTP query string full of key/value pairs, if a key is repeated then it overrides any earlier iterations of the same key.

$_SERVER['QUERY_STRING'] in PHP, where you’ll find the entire query string.

You could even implement your own query string handler that instead makes the first instance of each key the canonical one, if you really wanted.6

download=free parameter in the query string at “Images R Us”, e.g. making it

download=free&download=valuable! But we can’t: not without breaking the hash, which is calculated based on the entire query string (minus the &key=...

bit).

But with our new knowledge about appending to the input for SHA-1 first a padding string, then an extra block containing our payload (the variable we want to override and its new value), and then calculating a hash for this new block using the known output of the old final block as the IV… we’ve got everything we need to put the attack together.

Putting it all together

We have a legitimate link with the query string download=free&key=ee1cce71179386ecd1f3784144c55bc5d763afcc. This tells us that somewhere on the server, this is

what’s happening:

download=free with some special characters to replicate the padding that would otherwise be added to this final8 block, we can add a second block containing

an overriding value of download, specifically &download=valuable. The first value of download=, which will be the word free followed by

a stack of garbage padding characters, will be discarded.

And we can calculate the hash for this new block, and therefore the entire string, by using the known output from the previous block, like this:

Doing it for real

Of course, you’re not going to want to do all this by hand! But an understanding of why it works is important to being able to execute it properly. In the wild, exploitable implementations are rarely as tidy as this, and a solid comprehension of exactly what’s happening behind the scenes is far more-valuable than simply knowing which tool to run and what options to pass.

That said: you’ll want to find a tool you can run and know what options to pass to it! There are plenty of choices, but I’ve bundled one called hash_extender into my example, which will do the job pretty nicely:

$ docker exec hash_extender hash_extender \

--format=sha1 \

--data="download=free" \

--secret=16 \

--signature=ee1cce71179386ecd1f3784144c55bc5d763afcc \

--append="&download=valuable" \

--out-data-format=html

Type: sha1

Secret length: 16

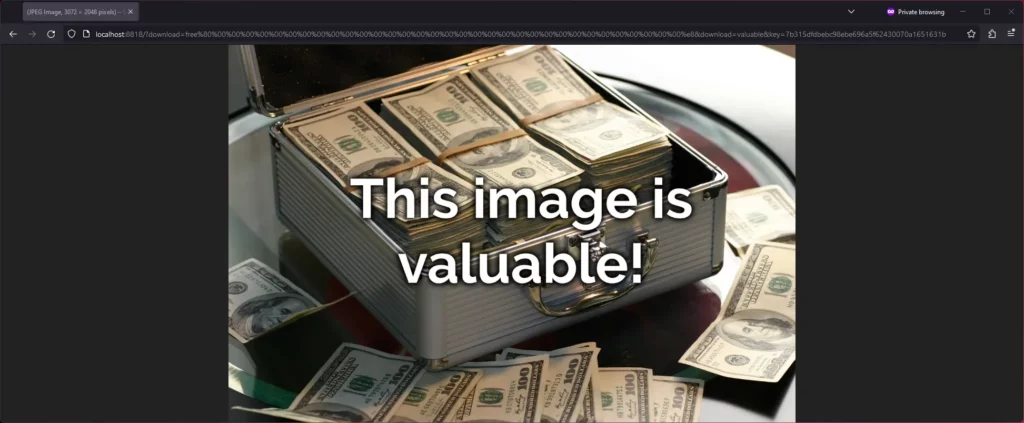

New signature: 7b315dfdbebc98ebe696a5f62430070a1651631b

New string: download%3dfree%80%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%e8%26download%3dvaluable

I’m telling hash_extender:

- which algorithm to use (

sha1), which can usually be derived from the hash length, - the existing data (

download=free), so it can determine the length, - the length of the secret (

16bytes), which I’ve guessed but could brute-force, - the existing, valid signature (

ee1cce71179386ecd1f3784144c55bc5d763afcc), - the data I’d like to append to the string (

&download=valuable), and - the format I’d like the output in: I find

htmlthe most-useful generally, but it’s got some encoding quirks that you need to be aware of!

hash_extender outputs the new signature, which we can put into the key=... parameter, and the new string that replaces download=free, including

the necessary padding to push into the next block and your new payload that follows.

Unfortunately it does over-encode a little: it’s encoded all the& and = (as %26 and %3d respectively), which isn’t what we

wanted, so you need to convert them back. But eventually you end up with the URL:

http://localhost:8818/?download=free%80%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%e8&download=valuable&key=7b315dfdbebc98ebe696a5f62430070a1651631b.

And that’s how you can manipulate a hash-protected string without access to its salt (in some circumstances).

Mitigating the attack

The correct way to fix the problem is by using a HMAC in place

of a simple hash signature. Instead of calling sha1( SECRET_KEY . urldecode( $params ) ), the code should call hash_hmac( 'sha1', urldecode( $params ), SECRET_KEY

). HMACs are theoretically-immune to length extension attacks, so long as the output of the hash function used is

functionally-random9.

Ideally, it should also use hash_equals( $validDownloadKey, $_GET['key'] ) rather than ===, to mitigate the possibility of a timing attack. But that’s another story.

Footnotes

1 This attack isn’t SHA1-specific: it works just as well on many other popular hashing algorithms too.

2 SHA-1‘s blocks are 64 bytes long; other algorithms vary.

3 For SHA-1, the padding bits

consist of a 1 followed by 0s, except the final 8-bytes are a big-endian number representing the length of the message.

4 SHA-1‘s IV is 67452301 EFCDAB89 98BADCFE 10325476 C3D2E1F0, which you’ll observe is little-endian counting from 0 to

F, then back from F to 0, then alternating between counting from 3 to 0 and C to F. It’s

considered good practice when developing a new cryptographic system to ensure that the hard-coded cryptographic primitives are simple, logical, independently-discoverable numbers like

simple sequences and well-known mathematical constants. This helps to prove that the inventor isn’t “hiding” something in there, e.g. a mathematical weakness that depends on a

specific primitive for which they alone (they hope!) have pre-calculated an exploit. If that sounds paranoid, it’s worth knowing that there’s plenty of evidence that various spy

agencies have deliberately done this, at various points: consider the widespread exposure of the BULLRUN programme and its likely influence on Dual EC

DRBG.

5 The padding characters I’ve used aren’t accurate, just representative. But there’s the right number of them!

6 You shouldn’t do this: you’ll cause yourself many headaches in the long run. But you could.

7 It’s also not always obvious which inputs are included in hash generation and how they’re manipulated: if you’re actually using this technique adversarily, be prepared to do a little experimentation.

8 In this example, the hash operates over a single block, but the exact same principle applies regardless of the number of blocks.

9 Imagining the implementation of a nontrivial hashing algorithm, the predictability of whose output makes their HMAC vulnerable to a length extension attack, is left as an exercise for the reader.