What’s that, girl? Two children are lost somewhere in this bookshop?

Yeah, I should probably find them and take them home for lunch.

Just visited the Logos Hope, an ocean-going, volunteer-staffed floating book fair (run by a Christian charity, but it’s not-TOO-religiousy inside, if that’s not your jam) that’s coincidentally docked for a fortnight right next door to my hotel on Trinidad!

What a strange concept. Fun diversion though.

There are two particular varieties of email address that I don’t often see, but I’ve been known to ridicule when I have:

OurHouseName@example.com. These always seemed to me to undermine one of the

single-best things about an email address compared to postal mail – that they don’t change when you move house!1

MrAndMrsSmith@example.net. These make me want to scream “You know email addresses are basically

free, right? You don’t have to share one!” Even back when most people got their email address directly from their dial-up provider, most ISPs offered some number of addresses (e.g. five).

If you’ve come across either of the above before, there’s… perhaps a reasonable chance that it was in the possession of somebody born before 1960 (and the older, the more-likely)2.

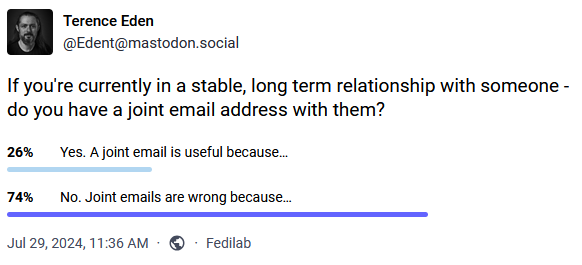

I found myself thinking about this as I clicked the “No” button on a poll by Terence Eden that asked whether I used a “shared” email address when in a stable long-term relationship.

It wasn’t until after I clicked “No” that I realised that, in actual fact, I have had multiple email addresses that I’ve share with significant other(s). And more than that, sometimes they’ve been geographically-based! What’s going on?

I’ve routinely had domains or subdomains that I’ve used to represent a place that I live. They’re convenient for when you want to give somebody a short web address which’ll take them to a page with directions to you and links to your location in a variety of different services and formats.

And by that point, you might as well have an email alias, e.g. all@myhouse.example.org, that forwards on email to, well, all the adults at the house. What I’ve

described there is, after a fashion, a shared email address tied to a geographical location. But we don’t ever send anything from it. Nor do we use it for any kind of

personal communication with anybody outside the house.

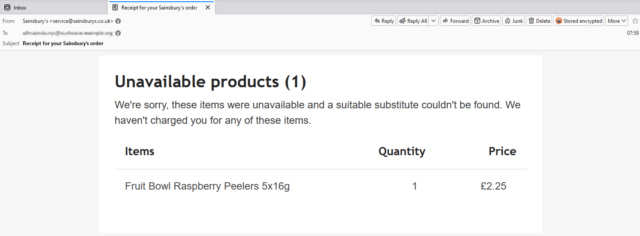

We don’t give out these all@ addresses (or their aliases: every company gets their own) to people willy-nilly. But they’re useful for shared services that send

automated emails to us all. For example:

Sure, the need for most of these solutions would evaporate instantly if more services supported multi-user or delegated access3. But outside of that fantasy world, shared aliases seem to be pretty useful!

1 The most ill-conceived example of geographically-based email addresses I’ve ever seen

came from a a 2003 proposal by then-MP Derek Wyatt, who proposed that the domain name part of every single email address should contain not

only the country of the owner (e.g. .uk) but also their complete postcode. He was under the delusion that this would somehow prevent spam. Even ignoring the

immense technical challenges of his proposal and the impossibility of policing it across the borders of every country that uses email… it probably wouldn’t even be

effective at his stated goal. I’ll let The Register take it from here.

2 No ageism intended: I suspect that the phenomenon actually stems from the fact that as email took off in the noughties this demographic who were significantly more-likely than younger folks to have (a) a very long-term home that they didn’t anticipate moving out of any time soon, and (b) an existing anticipation that people and companies wrote to them as a couple, not individually.

3 I’d love it if the grocery delivery sites would let multiple “accounts”, by mutual consent, share a delivery slot, destination, and payment method. It’d be cool to know that we could e.g. have a houseguest and give them temporary access to a specific order that was scheduled for during their stay. But that’s probably a lot of work for very little payoff if you’re busy running a supermarket.

Needed new UPS batteries.

Almost bought from @insight_uk but they require registration to checkout.

Purchased from @SourceUPSLtd instead.

Moral: having no “guest checkout” costs you business.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

For sellers, Amazon is a quasi-state. They rely on its infrastructure — its warehouses, shipping network, financial systems, and portal to millions of customers — and pay taxes in the form of fees. They also live in terror of its rules, which often change and are harshly enforced.

…

…the only way back from suspension is to “confess and repent,” she says, even if you don’t think you’ve done anything wrong. “Amazon doesn’t like to see finger-pointing.”

Suppose you have a competitor on Amazon Marketplace. Based on this article, the following strategies are pretty much fair game and are likely to result in immediate suspension of your competitor’s account:

Amazon don’t like controversy, so they always side against the seller. A great illustration as to why it’s dangerous when we let companies (like Amazon) have the power of judiciaries without the responsibilities of democracies.

I’m confused, @sainsburys.

What is the difference between these two products? What differentiates a “chunk” from a “piece” of pineapple? #pineapple #confused

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

false

There aren’t many great things to write about Hounslow, other than me being in it isn’t the sort of place that brings in visitors. There’s a tired shopping centre, an Asda (whose car park has just been closed), lots of planes going over and Hounslow Heath, which frankly is just a large bit of scrubland whatever their website tells you about it being a “Local Nature Reserve and Site of Importance for Nature Conservation (of Metropolitan Importance)” I really wouldn’t make the effort to see it.

What Hounslow does boast is three, yes THREE Poundlands. I have no idea why we need three Poundlands, especially as the high street also boasts a brand new PoundWorld, a 99p shop and a 97p shop. Seriously, the three Poundlands are literally five minute walks away from each other. You may have seen the press this week about Poundland’s new sex toy range. Sex toys, in Poundland, for a quid?! Yes, indeedy!

Actually, they first released their pound bullet vibe a few years back (how did I miss this?!) but now they have extended their range further. It’s called Nooky. Of course it is.

…

This review of Co-op originally appeared on Google Maps. See more reviews by Dan.

Convenient supermarket with reasonable parking. However, recent changes to the layout of the store have dramatically reduced the availability of many product lines (and it’s hard to see exactly why the changes have been made): the frozen section, for example, is now particularly sparse.

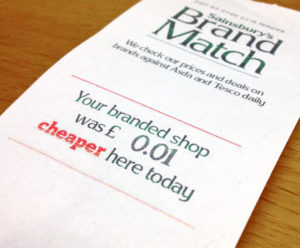

It’s been almost five years since Sainsbury’s supermarkets pioneered the “brand match” idea, which rivals Tesco and Asda later adopted into their own schemes, and I maintain that it’s one of the cleverest pieces of marketing that I’ve ever seen. In case you’ve not come across it before, the principle is this: if your shopping would have been cheaper at one of their major competitors, these supermarkets will give you a voucher for the difference right there at the checkout. Properly advertised (e.g. not in ways that get banned for being misleading), these schemes are an incredibly-compelling tool: no consumer should say no to getting the best possible prices without having to shop around, right?

But it’s nowhere near as simple as that. For a start, the terms and conditions (Asda, Sainsbury’s, Tesco) put significant limitations on how the schemes work. You need to buy at least a certain number of items (8 at Asda, 10 at the other two). Those items must be directly-comparable to competitors’ items: which basically means that only branded products count, but even among them, the competitor must stock the exact same size or else it doesn’t count, even if it would have been cheaper to buy two half-sized products there. There are upper limits to the value of the vouchers (usually £10) and the number that you can use per transaction or per month. “Buy X get Y free” offers are excluded. And there’s a huge list of not-compared products which may include batteries, toys, DVDs, some alcoholic drinks, cosmetics, homeware, flowers, baby formula, light bulbs, books, and anything (even non-medicines) from the pharmacy aisle.

But even if it only applies to some of your shopping – the stuff that’s easy to directly compare – it’s still a good deal, right? You’re getting money back towards what you would have saved if you’d have gone up the road? Not necessarily. Let us assume that on average the prices of these three supermarket giants are pretty much the same. Individual products might each be a little more expensive here and a little cheaper there, but if you buy a large enough trolley-load you’re not going to notice the difference. Following me so far? What does this mean for the voucher: it means that it no longer remotely represents what you would have saved if you’d actually been “shopping around”. Let’s take a concrete example:

Suppose that this is my somewhat-eccentric shopping list (I wanted to select a variety of comparable branded products), and I’m considering shopping at either Sainsbury’s or Tesco:

Not too unreasonable, right? I’ve made a spreadsheet showing my working, where you’ll see today’s prices for each of these items (along with the actual brands and package sizes I’ve selected), if you’d like to check my maths, because here comes the clever bit.

Based on my calculation, taking my imaginary shopping list to Sainsbury’s will ultimately cost me £52.85. Taking it to Tesco will cost me £54.13. Pretty close, right, and I’m not likely to care about the

difference because Tesco would give me a £1.28 voucher off my next shop which makes up for the difference (note that Sainsbury’s wouldn’t reciprocate in kind if it were the other way

around, after a policy change they made late last year). But that’s not

actually a true representation of the value of ‘shopping around’. As my spreadsheet shows, if I were to buy each item on my list at the supermarket that was cheapest, it’d only cost me

a total of £43.75: that’s a saving of £9.10 (or about 17% off my entire shop) compared to the cheapest of these supermarkets. These schemes don’t give

you a real “best of all worlds”. Instead, they give you, at most, a “best of all worlds, assuming that you’re still going to be lazy enough to only shop in one place”.

If you’re particularly devious of mind, you can exploit this. For example, suppose I went to Tesco but when I reached the checkout I split my shopping into two transactions.

The first transaction contains the frozen goods, milk, wine, dough balls, flapjacks, and mini rolls. This comes out at £33.73, which is £10.38 more than Sainsbury’s would charge me for the same goods. Tesco

therefore gives me a £10 voucher, which I immediately use on the second batch of shopping: the one which contains goods that are cheaper than their Sainsbury’s

equivalents. The total price of my shopping: £44.13 – only 38p more than if I’d gone to both

supermarkets and bought only the best-value goods from each (the 38p discrepancy comes from the fact that Tesco won’t ever give you a voucher worth more than £10, no matter how much

you’re losing out).

It’s not even that hard to do. Obviously, somebody’s probably written an app for it, but even if you’re just doing it by guesswork you can get a better result than just piling all of your shopping onto the conveyor belt together. Simply put the things which seem like a good deal (all of the discounted products, plus anything that feels like it’s good value) at one end of your trolley, and unload those things last. Making sure that you’ve got at least ten items on the conveyor, ‘split’ your shopping somewhere towards the beginning of these items. Then take any voucher you get from your first load, and apply it to the second.

It’s pretty easy, so long as you don’t mind looking like a bit of a tool at the checkout.

But to most people, most of the time, this is nothing more than a strong and compelling piece of marketing. Either you get reminded that you allegedly “saved money”, on a piece of paper that probably goes into your wallet and helps to combat buyer’s remorse, or else we get told that we paid a particular amount more than we needed to, and are offered the difference back so long as we return to the same store within the next fortnight. Either way, the supermarket wins your loyalty, which – for a couple of pence on each transaction (assuming that the customer doesn’t lose the voucher or otherwise fail to get an opportunity to use it) – is a miniscule price to pay.

This blog post is the second in a series about buying our first house. If you haven’t already, you might like to read the first part.

When Ruth, JTA and I first set out to look at houses, we didn’t actually plan on buying one. We’d just gotten to the point where buying one felt like an imminent logical step, and so we decided to start looking around Oxford to see what kind of thing we might be able to get (and what it would cost us, if we did). Our thinking was that, by looking around a few places, we’d have some context from which to springboard our own discussions about what property we’d one day like to own.

There’s something about “window shopping” for houses that’s liberating and exciting. We don’t need a house – we’ve got somewhere to live – but we’re going to come and look around anyway. Once you’re on their lists, estate agents will bombard you with suggestions of places that you might like, and you feel a little like they’re your servants, running around trying to please you (in actual fact, almost the opposite is true: they’re working on behalf of the seller… although it’s certainly in their interest to get the property sold promptly so that they can take their cut!).

But as we got into the swing of things, we discovered that we were ready to buy already. Between our savings (and, in particular, boosted by the first parts of my inheritance following my dad’s death last year, as we’re finally getting his estate sorted out), we actually have an acceptable deposit for a mortgage, and our renewal on our current place was looming fast. None of us having bought a house before, we did a bit of reading and decided that our first step probably ought to be to work out how much can we borrow. You know, just to make our window-shopping a little more believable. Maybe.

One of the estate agents we dealt with introduced us to a chap called Stefan Cork, a mortgage broker working as part of the Mortgage Advice Bureau network. We were still only window-shopping at this point, but hey: if we were going to be allowed some free, no-commitment mortgage advice, then we might as well work out how much we could potentially borrow, right? After checking his credentials (the three questions you should ask every mortgage broker), I spoke to Stefan on the phone, and talked him through our situation. I described our unusual relationship structure (which he took in his stride) and the way that we means-assess our household contributions, alongside more mundane details like how much we earn and what kind of deposit we could rustle up. He talked us through our options and ballparked some of the kinds of numbers we’d be looking at, if we went ahead and got a mortgage.

And somehow, somewhere along the line, our perspective switched. Instead of looking at houses just to give us a feel for what we might buy, “maybe next year”, we were genuinely looking to buy a house now. We re-visited some of the places we’d seen already, and increased our search of places we hadn’t yet seen. Over time, and by a process of elimination (slow Internet area; too many hills; too narrow staircases; too expensive; too wonky), we cut down our options to just three potential properties. And then just two. And then we came to an impasse.

So… we put offers on both. Under the law of England and Wales, a property purchase isn’t binding until the contracts have exchanged hands. Sellers benefit (and buyers suffer) from this all of the time, because it permits gazumping: even after the buyers have spent money on lawyers, mortgage applications, surveys and searches, the seller can change their mind and accept a higher offer from a different prospective buyer! But this legal quirk can work for buyers, too: in our case, we were able to put offers in of what we were willing to pay for each of two properties (different values, at that), and let them know that the first one of the two to agree to our price would be the one to get the sale!

Haggling for a house in this way felt incredibly ballsy (I’d been nominated as the negotiator on behalf of the other Earthlings), but it played against the psychology of our sellers. Suddenly, instead of being in a position of power (“no, we won’t accept that offer… go a little higher”), the sellers were made to feel that if they didn’t accept our offers (which were doubtless lower than they had hoped), they’d have a 50% chance of losing the sale entirely. When there are hundreds of thousands of pounds on the line, being able to keep your cool and show that you’re willing to go elsewhere is an incredibly powerful negotiating tactic.

True to our word: when one of them came back and accepted our offer, we withdrew the offer on the other house and began the (lengthy) paperwork to start getting the purchase underway. But that can wait for another blog post.

I always wondered where Paul got all of the weirder parts of his music collection. Turns out Amazon just starts recommending it to you once you start looking in the right places:

I recently bought three board games (Munchkin 3, Fluxx and Puerto Rico) from ACME Computer Games in Bangor (yes, I know, the same guys who got confused over my order before…). Somehow, I don’t think they get many e-customers: I just grabbed this screenshot from their web site –

Notice that I’m looking at Munchkin 3, and the Customers Who Bought This Also Bought says… yes, my two other purchases. And nothing else. Hmm.

Still no sign of my order, or any word from them (I placed the order over a week ago). Better give them a bell, I think.

As this article from the BBC and this article on icWales states,Aberystwyth is getting a sex shop (you can confirm it for yourselves by checking the pink banner at the top of the official web site.

That’ll save me spending so much on mail order goods.

Butterfingers gave me a courtesy call at work this morning to tell me that my juggling gear will be delivered tomorrow. Which is nice.

It’s a stupidly hot day. The office needs desk fans. I’m melting here. I’ve been to the kitchen three times so far just to soak my head/hair from the tap to keep me cool. It’s just evaporating off. I’ve drunk all my mago juice and my cranberry juice.

There’s a storm predicted for Friday. Hopefully this one will actually happen as scheduled and the air temperature and pressure will drop a bit.

My arms are sweaty and sticking to the desk. Gonna take a walk outside.