The elder of our two cars is starting to exhibit a few minor, but annoying, technical faults. Like: sometimes the Bluetooth connection to your phone will break and instead of music, you just get a non-stop high-pitched screaming sound which you can suppress by turning off the entertainment system… but can’t fix without completely rebooting the entire car.

The “wouldn’t you rather listen to screaming” problem occurred this morning. At the time, I was driving the kids to an activity camp, and because they’d been quite enjoying singing along to a bangin’ playlist I’d set up, they pivoted into their next-most-favourite car journey activity of trying to snipe at one another1. So I needed a distraction. I asked:

We’ve talked about homonyms and homophones before, haven’t we? I wonder: can anybody think of a pair of words that are homonyms that are not homophones? So: two words that are spelled the same, but mean different things and sound different when you say them?

This was sufficiently distracting that it not only kept the kids from fighting for the entire remainder of the journey, but it also distracted me enough that I missed the penultimate turning of our journey and had to double-back2

…in English

With a little prompting and hints, each of the kids came up with one pair each, both of which exploit the pronunciation ambiguity of English’s “ea” phoneme:

-

Lead, as in:

- /lɛd/ The pipes are made of lead.

- /liːd/ Take the dog by her lead.

-

Read, as in:

- /ɹɛd/ I read a great book last month.

- /ɹiːd/ I will read it after you finish.

These are heterophonic homonyms: words that sound different and mean different things, but are spelled the same way. The kids and I only came up with the two on our car journey, but I found many more later in the day. Especially, as you might see from the phonetic patterns in this list, once I started thinking about which other sounds are ambiguous when written:

- Tear (/tɛr/ | /tɪr/): she tears off some paper to wipe her tears away.

- Wind (/waɪnd/ | /wɪnd/): don’t forget to wind your watch before you wind your horn.

- Live (/laɪv/ | /lɪv/): I’d like to see that band live if only I could live near where they play.

- Bass (/beɪs/ | /bæs/): I play my bass for the bass in the lake.

- Bow (/baʊ/ | /boʊ/): take a bow before you notch an arrow into your bow.

- Sow (/saʊ/ | /soʊ/): the pig and sow ate the seeds as fast as I could sow them.

- Does (/dʌz/ | /doʊz/): does she know about the bucks and does in the forest?

(If you’ve got more of these, I’d love to hear read them!)

…in other Languages?

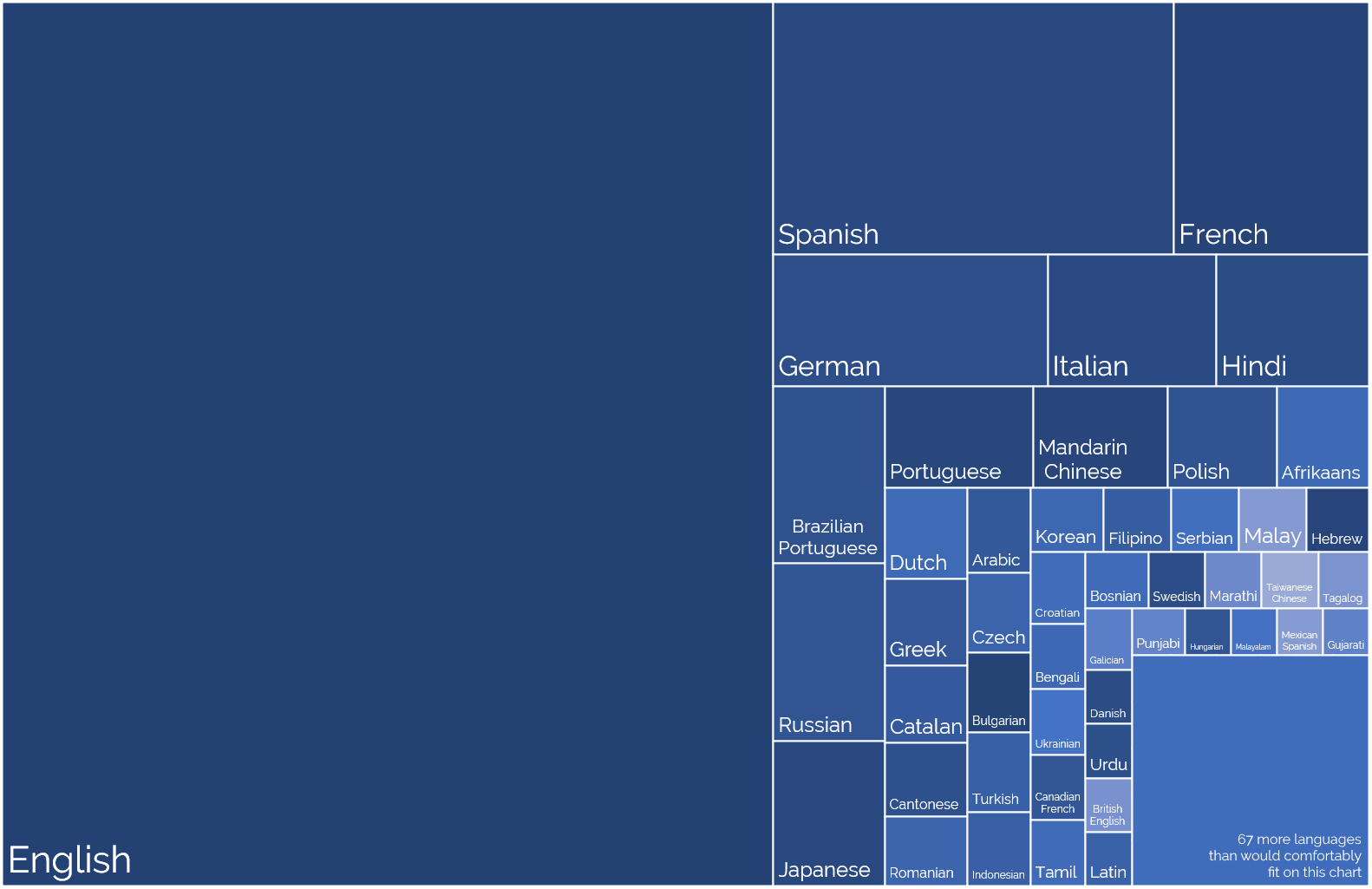

I’m interested in whether heterophonic homonyms are common in any other languages than English? English has a profound advantage for this kind of wordplay3, because it has weakly phonetics (its orthography is irregular: things aren’t often spelled like they’re said) and because it has diverse linguistic roots (bits of Latin, bits of Greek, some Romance languages, some Germanic languages, and a smattering of Celtic and Nordic languages).

With a little exploration I was able to find only two examples in other languages, but I’d love to find more if you know of any. Here are the two I know of already:

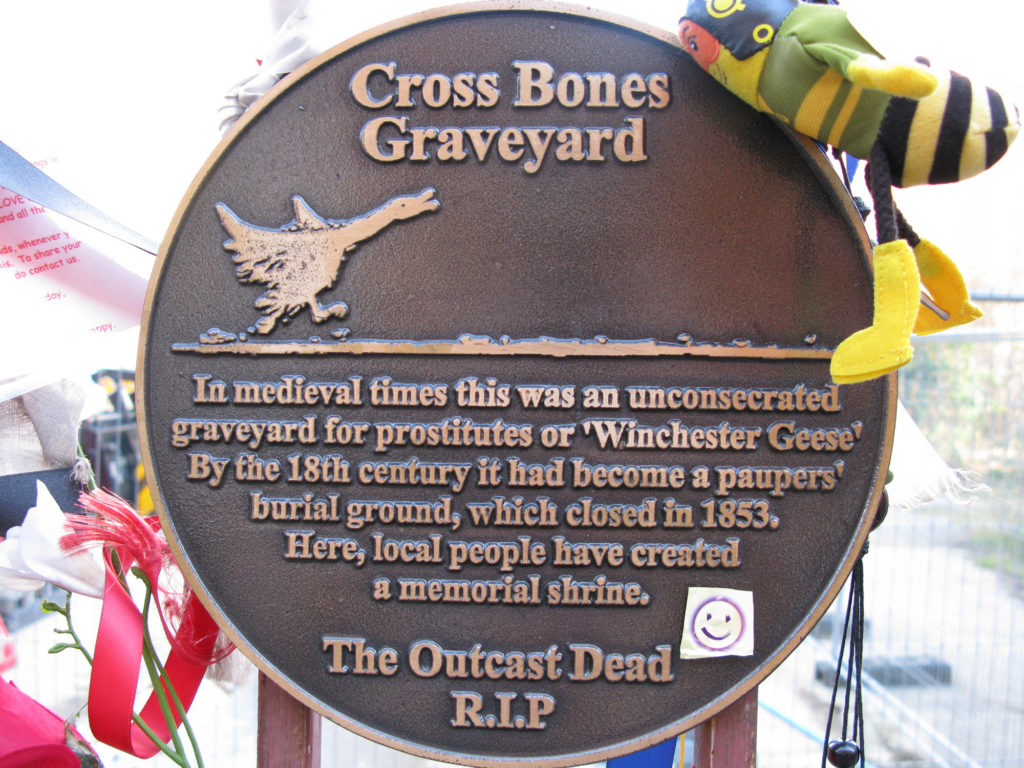

- In French I found couvent, which works only thanks to a very old-fashioned word:

- /ku.vɑ̃/ means convent, as in – where you keep your nuns, and

- /ku.və/ means sit on, but specifically in the manner that a bird does on its egg, although apparently this usage is considered archaic and the word couver is now preferred.

- In Portugese I cound pelo, which works only because modern dialects of Portugese have simplified or removed the diacritics that used to differentiate the

spellings of some words:

- /ˈpe.lu/ means hair, like that which grows on your head, and

- /ˈpɛ.lu/ means to peel, as you would with an orange.

If you speak more or different languages than me and can find others for me to add to my collection of words that are spelled the same but that are pronounced differently, I’d love to hear them.

Special Bonus Internet Points for anybody who can find such a word that can reasonably be translated into another language as a word which also exhibits the same phenomenon. A pun that can only be fully understood and enjoyed by bilingual speakers would be an especially exciting thing to behold!

Footnotes

1 I guess close siblings are just gonna go through phases where they fight a lot, right? But if you’d like to reassure me that for most it’s just a phase and it’ll pass, that’d be nice.

2 In my defence, I was navigating from memory because my satnav was on my phone and it was still trying to talk over Bluetooth to the car… which was turning all of its directions into a high-pitched scream.

3 If by “advantage” you mean “is incredibly difficult for non-native speakers to ever learn fluently”.