In 2023 I published an updated version of this blog post. See that post for the latest tips on managing polyfamily finances in a socialist manner.

For the last four years or so, Ruth, JTA and I (and during their times living with us, Paul and Matt) have organised our finances according to a system of means-assessment. I’ve mentioned it to people on a number of ocassions, and every time it seems to attract interest, so I thought I’d explain how we got to it and how it works, so that others might benefit from it. We think it’s particularly good for families consisting of multiple adults sharing a single household (for example, polyamorous networks like ours, or families with grown children) but there are probably others who’d benefit from it, too – it’s perfectly reasonable for just two adults with different salaries to use it, for example. And I’ve made a sample spreadsheet that you’re welcome to copy and adapt, if you’d like to.

How we got here

After I left Aberystwyth and Ruth, JTA, Paul and I started living at “Earth”, our house in Headington, we realised that for the first time, the four of us were financially-connected to one another. We started by dividing the rent and council tax four ways (with an exemption for Paul while he was still looking for work), splitting the major annual expenses (insurance, TV license) between the largest earners, and taking turns to pay smaller, more-regular expenses (shopping, bills, etc.). This didn’t work out very well, because it only takes two cycles of you being the “unlucky” one who gets lumbered with the more-expensive-than-usual shopping trip – right before a party, for example – before it starts to feel like a bit of a lottery.

Our solution, then, was to replace the system with a fairer one. We started adding up our total expenditures over the course of each month and settling the difference between one another at the end of each month. Because we’re clearly raging socialists, we decided that the fairest (and most “family-like”) way to distribute responsibility was by a system of partial means-assessment: de chacun selon ses facultés.

We started out with what we called “75% means-assessment”: in other words, a quarter of our shared expenditures were split evenly, four ways, and three-quarters were split proportionally in accordance with our gross income. We arrived at that figure after a little dissussion (and a computerised model that we could all play with on a big screen). Working from gross income invariably introduces inequalities into the system (some of which are mirrored in our income tax system) but a bigger unfairness came – as it does in wider society – from the fact that the difference between a very-low income and a low income is significantly more (from a disposable money perspective) than the difference between a low and a high income. This was relevant, because ‘personal’ expenses, such as mobile phone bills, were not included in the scheme and so we may have penalised lower-earners more than we had intended. On the other hand, 75% means-assessment was still significantly more-“communist” than 0%!

When I mentioned this system to people, sometimes they’d express surprise that I (as one of the higher earners) would agree to such an arrangement: the question was usually asked with a tone that implied that they expected the lower earners to mooch off of the higher earners, which (coupled with the clearly false idea that there’s a linear relationship between the amount of work involved in a job and the amount that it pays) would result in a “race to the bottom”, with each participant trying to do the smallest amount of work possible in order to maximise the degree to which they were subsidised by the others. From a game theory perspective, the argument makes sense, I would concede. But on the other hand – what the hell would I be doing agreeing to live with and share finances with (and then continuing to live with and share finances with) people whose ideology was so opposed to my own in the first place? Naturally, I trusted my fellow Earthlings in this arrangement: I already trusted them – that’s why I was living with them!

How it works

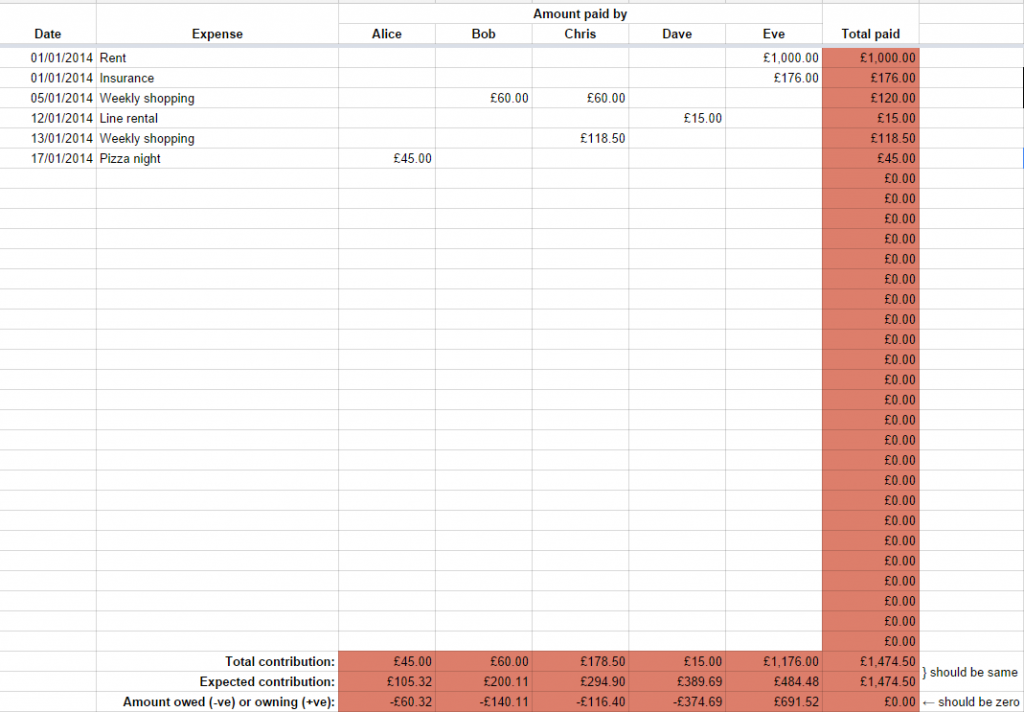

We’ve had a few iterations, but we eventually settled on a system at a higher rate of means-assessment: 100%! It’s not perfect, but it’s the fairest way I’ve ever been involved with of sharing the costs of running a house. I’ve put together a spreadsheet based on the one that we use that you can adapt to your own household, if you’d like to try a fairer way of splitting your bills – whether there are just two of you or lots of you in your home, this provides a genuinely equitable way to share your costs.

The sheet I’ve provided – linked above – is not quite like ours: ours has extra features to handle Ruth and I’s fluctuating income (mine because of freelance work, Ruth’s because she’s gradually returning to work following a period of maternity leave), an archive of each month’s finances, tools to help handle repayments to one another of money borrowed, and convenience macros to highlight who owes what to whom. This is, then, a simplified version from which you can build a model for your own household, or that you can use as a starting point for discussions with your own tribe.

Start on the “People” sheet and tell it how many participants your household has, their names, and their relative incomes. Also add your proposed level of means-assessment: anything from 0% to 100%… or beyond, but that does have some interesting philosophical consequences.

Then, on the “Expenses” sheet, record each thing that your household pays for over the course of each month. At the bottom, it’ll total up how much each person has paid, and how much they would have been expected to pay, based on the level of your means-assessment: at 0%, for example, each person would be expected to pay 1/N of the total; at the other extreme (100%), a person with no income would be expected to make no contribution, and a person with twice the income of another would be expected to pay twice as much as them. It’ll also show the difference between the two values: so those who’ve paid less than their ‘share’ will have negative numbers and will owe money to those who’ve paid more than their share, indicated by positive numbers. Settle the difference… and you’re ready to roll on to the next month.

Now you’re equipped to employ a (wholly or partially) means-assessed model to your household finances. If you adapt this model or have ideas for its future development, I’d love to hear them.