This has been a draft blog post since ~2019, with minor additions since then.

Perhaps it’s finally time to share these ten weird… “games” (or game-adjacent media)… that I’ve seen.

Maybe you’ll “get” them. If not, maybe they’re just for me.

1. It is as if you were playing chess

Where could I possibly start this list if not with eccentric games-as-art proponent Pippin Barr. Created in 2016, It is as if you were playing chess is an interactive experience that encourages you to mimic the physical movements of playing a digital chess game, without actually ever looking at a chessboard.

Years later I’d argue that the experience of its… sequel?… It is as if you were on your phone, is very similar. Especially to an outside observer, watching you tap and swipe at your mobile device as if you were using your mobile device: it’s almost like an alien’s guide to blending-in with humans.

Is is even a game? Pippin himself mused over this in a blog post1. He went on to make several others in the same genre, of which It is as if you were making love is perhaps the most off-the-wall. Give that a go, too.

Whether or not they’re games, these are art, and they are compelling.

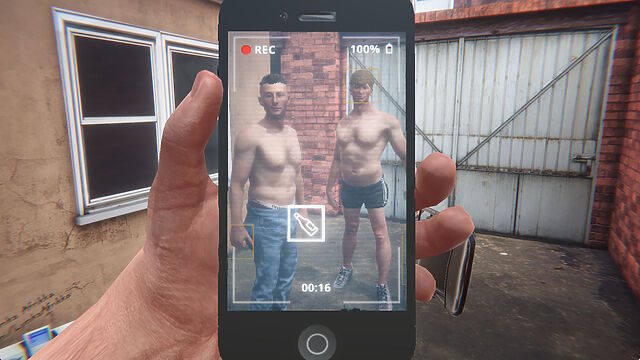

2. Hard Lads

Back in 2016, a video briefly trended on YouTube called “British Lads Hit Each Other with Chair”.

It’s a 67-second portrait video featuring four partially-dressed young men somewhere in what looks like Tyneside. Two of them kiss before one of the pair swigs from a spirits bottle and takes a drag from a cigarette, throwing both onto the floor afterwards3.

Finally, the least-dressed young man (seemingly with the consent of all involved) repeatedly strikes the drinker/smoker with a folding chair.

It’s… quite something.

In his blog post Hard Lads as an important failure, the game’s creator Robert Yang describes it as “neorealist fumblecore”, and goes into wonderful detail about the artistic choices he made in creating it. The game is surreal, queer, and an absolute masterpiece.

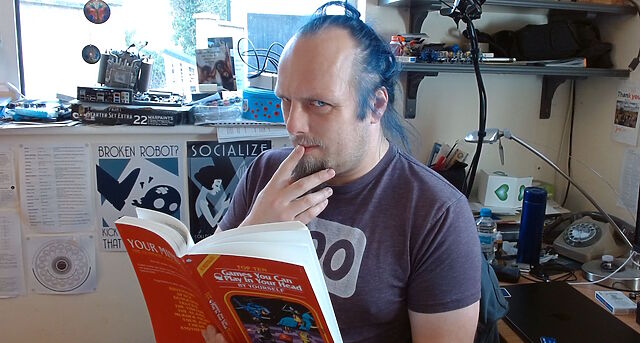

3. Top Ten Games You Can Play In Your Head By Yourself

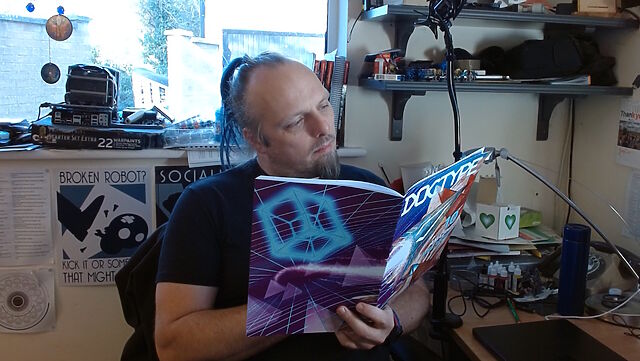

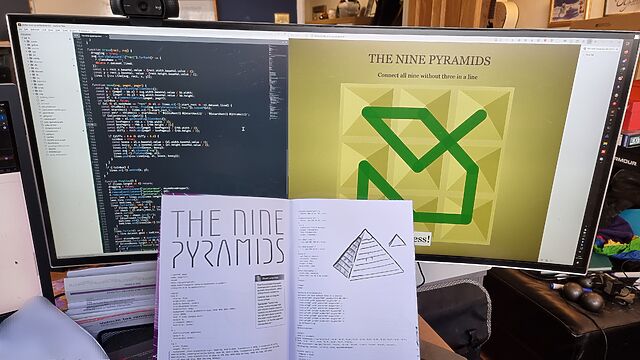

Let’s sidestep a moment out of video games and take a look at a book.

Top Ten Games You Can Play In Your Head By Yourself, edited by Sam Gorski (founder of Corridor Digital) and D. F. Lovett and based on an original series of gamebooks written pseudonymously by “J. Theophrastus Bartholomew”, initially looks like exactly what it claims to be. That is, a selective reprint of a very-1980s-looking series of solo roleplaying game prompts.

Except that’s clearly a lie. There’s no evidence that J. Theophrastus Bartholomew exists as an author (even used as a pen name), nor do any of the fourteen books credited to him in the foreword. The alleged author only as a framing device by the actual authors: the “editors”.

Superficially, the book presents a series of ten… “prompts”, I suppose. It’s like reading the rules of a Choose Your Own Adventure gamebook, or else the flavour and background in an Advanced Dungeons & Dragons module.

Each prompt sets up a premise and describes it as if it would later integrate with a ruleset… but no ruleset is forthcoming. Instead, completing the story and also how to go about completing the story is left entirely up to the reader.

It’s disarming, like if a recipe book consisted of a list of dishes and cuisines, a little about the history and culture of each… and no instructions on how to make it.

But what’s most-weird about the book (and there’s plenty more besides) are the cross-references between the chapters4. Characters from one adventure turn up in another. Interstitial “Shadows and Treasures” chapters encourage you to reflect upon previous adventures and foreshadow those that follow.

There’s more on its RPGGeek page (whose existence surprised me!), along with a blog post by Lovett. They’re doing a horror-themed sequel, which I don’t feel the need to purchase, but I’d got to say from what I’ve seen so far that they’ve once-again really nailed the aesthetic.

I have no idea who the book is “for”, but it’s proven surprisingly popular in some circles.

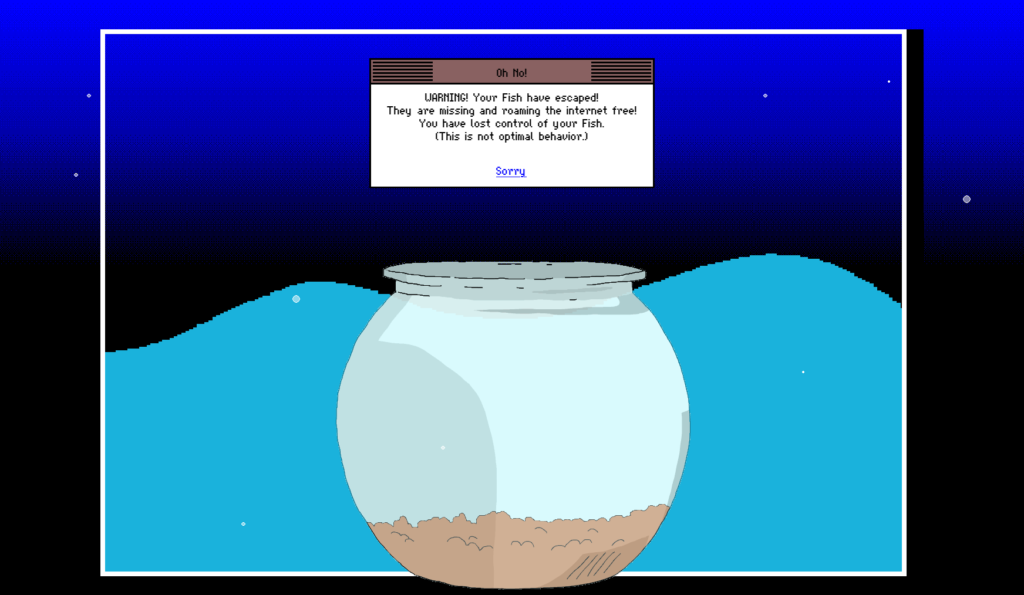

4. Mackerelmedia Fish

I reviewed this game shortly after its release in 2020 by the ever-excellent Natalie Lawhead. At the time, I said:

What is Mackerelmedia Fish? I’ve had a thorough and pretty complete experience of it, now, and I’m still not sure. It’s one or more (or none) of these, for sure, maybe:

- A point-and-click, text-based, or hypertext adventure?

- An homage to the fun and weird Web of yesteryear?

- A statement about the fragility of proprietary technologies on the Internet?

- An ARG set in a parallel universe in which the 1990s never ended?

- A series of surrealist art pieces connected by a loose narrative?

…

What I can tell you with confident is what playing feels like. And what it feels like is the moment when you’ve gotten bored waiting for page 20 of Argon Zark to finish appear so you decide to reread your already-downloaded copy of the 1997 a.r.k bestof book, and for a moment you think to yourself: “Whoah; this must be what living in the future feels like!”

…

Mackerelmedia Fish is a mess of half-baked puns, retro graphics, outdated browsing paradigms and broken links. And that’s just part of what makes it great.

Just because I wrote about it before doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t play it now, especially if you missed out on it during the insanity of Lockdown 1.0.

5. Ha-bee-tat

It’s a bitsy game thrown together in 9 days for a game jam, by Cicada Carpenter.

I wouldn’t even have discovered this game were it not for the amazing-but-weird blog post “Every bee videogame reviewed by accuracy”, by Paolo Pedercini, who wrote:

As an amateur beekeeper, semi-professional game designer, and generally pedantic person, I decided to play all the games I could find on the subject and rate them according to their “realism”. The rating goes from one (⬢⬡⬡⬡⬡) to five (⬢⬢⬢⬢⬢) honeycomb cells.

I intentionally avoided all the games in which bees are completely anthropomorphized or function like a spaceship, and games in which bees play a secondary role. I did include short and semi-abstract games when they referenced the bees actual behavior. Realism is not a matter of visual definition or sheer procedural complexity. In my view, even a tiny game can capture something compelling about this fascinating insect.

Ha-bee-tat is one of only four games to which Paolo awards a full five honeycombs. And Paolo is picky, so that’s high praise indeed for the realism of this game, which is – get this – also surprisingly educational on the subject of different species of bee! Neat!

6. Shadows out of Time

This Twine-based adventure was released for my last Halloween at the Bodleian, based mostly upon the work of my then-colleague Brendon Connelly. We were aiming for something slightly unnerving, slightly Lovecraftian… and very Bodleian Libraries.

Obviously I’ve written about it before, but if I can just take a moment to explain what we were going for, which didn’t come out in any of the IFDB reviews or anything:

The story is cyclical: the protagonist keeps waking up, completely alone, in a seemingly abandoned world, having nodded off half way through The Shadow Out of Time in a Bodleian reading room. As they explore the eerie and empty world5, the protagonist catches vague glimpses of another figure moving around the space as well, always just out of reach in the distance or beyond a window. There are even hints that this other person has been following them: a book left open can be found closed again, or vice-versa, for example.

Eventually, exhausted, the character needs to rest, waking up again6 in order to continue their explorations, and it gradually becomes apparent that they are the ghost that haunts the library. The shadows they’re witnessing are echoes of their past and future self, playing through the permutations of the game as they remain trapped in an endless and futile chase with their own tail.

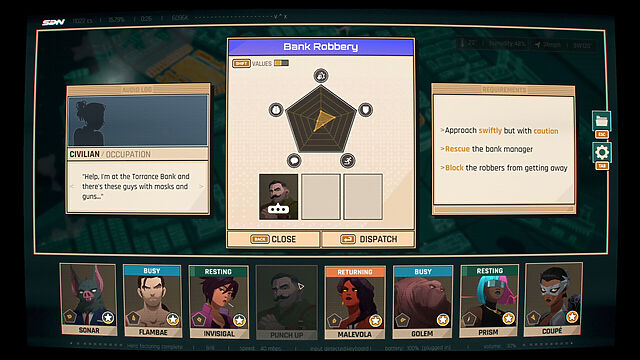

7. Metropoloid

When I first wrote about this video, I remarked that it was sad that it was under-loved, attracting only a few hundred views on YouTube and only a couple of dozen “thumbs up”. Six years on… I’m sad to say it’s not done much better for popularity, with low-thousands of views and, like, six-dozen “thumbs up”. Possibly this (lack of) reaction is (part of the reason) why its creator Yaz Minsky has kind-of gone quiet online these last few years.

So what it is?

Well, you know how you’ve probably never seen Metropolis with a musical score quite like the one composer Gottfried Huppertz intended? Well this… doesn’t solve that problem. Instead it re-scores the film with video game soundtracks from the likes of Metroid, Castlevania, Zelda, Mega Man, Final Fantasy, Doom, Kirby, and F-Zero, among others.

And it… works. It still deserves more love, so if you’ve got a spare couple of hours, put it on!

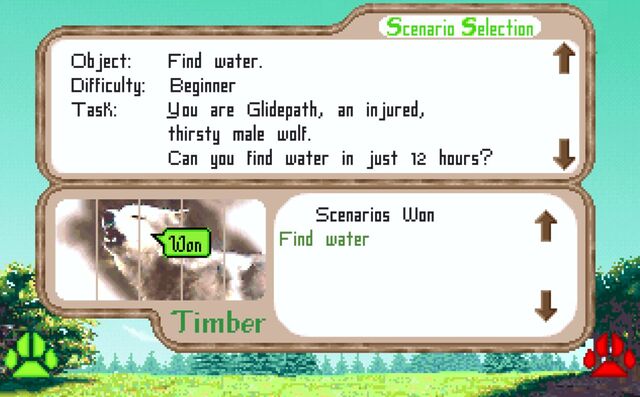

8. Wolf

Like Ha-bee-tat, this is a realistic, pixelated, educational video game about nature. It came out in 1994 but I didn’t get around to playing it until twenty-five years later in 2019, when I accidentally discovered it while downloading Wolfenstein to my DOSBox.

The game itself isn’t what makes this item weird. The weird bit is this 2018 review of the game, which reads:

AWOO AWOOOO. AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOOO.

AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOO AWOO. AWOO AWOO AWOOOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOO. AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOOOO AWOO AWOOOOO. AWOO AWOO AWOOOOOOO AWOO AWOOO AWOO AWOOOO AWOO.

AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOOO AWOO AWOO AWOO. AWOO AWOOOOOO AWOOOOOO AWOOOO AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOOOOO AWOO AWOOOOOO AWOO. AWOOOOOO AWOO AWOOOO AWOO AWOOOO AWOO AWOO. AWOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOOO AWOO AWOO AWOOOOO AWOO AWOOO AWOO. AWOOOO AWOOO AWOOOO AWOO AWOO.

…

It continues like that for a while.

What you’re seeing is a review of Wolf… but for wolves. I’m not aware of any other posts on that entire site that make the same gag, or anything like it. That’s weird. And brilliant.

9. Real World Third Person Perspective

People have done similar thinigs in a variety of ways, but this was one of the most-ambitious:

As part of a two-day hack project, these folks put together a mechanism to mount some cameras up a pole, from a backpack containing a computer, connected to a VR headset. The idea was that you’d be able to explore the world with the kind of “over-the-shoulder cam” that you might be used to in some varieties of videogame.

Theirs was just an experiment in proving what was possible within a “real world” game world. But ever since I saw this video, I’ve wondered about the potential to make what is functionally an augmented reality game out of it. With good enough spatial tracking, there’d be nothing to stop the world as-shown-to-your-eyes containing objects that aren’t present in the real world.

Like… what if you were playing Pokemon Go, but from a top down view of yourself as you go around and find creatures out and about in the real world. Not just limited to looking through your phone as a lens, you’d be immersed in the game in a whole new way.

I’m also really interested in what the experience of seeing yourself from the “wrong” perspective is like. Is it disassociating? Nauseating? Liberating? I’m sure we’ve all done one of those experiments where, by means of mirrors or props, we experience the illusory sensation of our hand being touched when it’s not actually our hand. What’s that like when you’re able to visually step completely out of your own body, and yet still move and feel it perfectly?

There are so many questions that this set-up raises, and I’m yet to see anybody try to answer them.

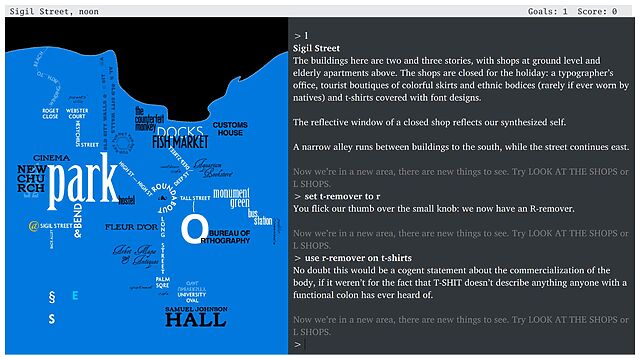

10. Counterfeit Monkey

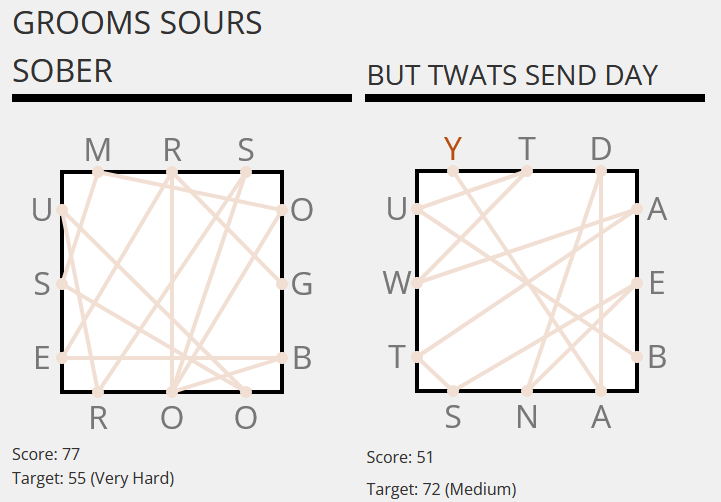

Finally, I can’t resist an opportunity to plug – not for the first time – my favourite interactive fiction game, Emily Short‘s Counterfeit Monkey, a game that started as an effort to make a tutorial on making a “T-Remover” like the one in Leather Goddesses of Phobos but grew into a sprawling wordplay-based puzzle adventure.

What makes it weird? The fact that there’s not really anything else quite like it. Within your first half hour or so of play you’ll probably have acquired your core toolkit – your full-alphabet letter remover, restoration gel, and monocle – and you’ll begin to discover that you can do just about anything with anything.

Find some BRANDY (I’m don’t recall if there is any in the game; this is just an example) and you can turn it into a BRAND, then into some BRAN,

then into a BRA7. And while there might not exist any puzzles in the game for which you’ll need a bra, each of these items will have a

full description when you look at it. Can you begin to conceive of the amount of work involved in making a game like this?

It’s now over a decade old and continues to receive updates as a community-run project! It’s completely free8,

and if you haven’t played it yet, congratulations: you’re about to have an amazing time. Pay attention to the tutorial, and be sure to use an interpreter that supports the

UNDO command (or else be sure to SAVE frequently!).

I remain interested in things that push the boundaries of what a “game” is or otherwise make the space “fun and weird”. If you’ve seen something I should see, let me know!

Footnotes

1 The blog post got deleted but the Wayback Machine has a copy.

2 Note you don’t get to see a video of me playing It is as if you were making love; you’re welcome.

3 Strangely – although it’s hard to say that anything in this video is more-strange than any other part – one of the “hard lads” friends’ then picks up his fag end and takes a drag

4 This, in case it wasn’t obvious to you already, is likely to be a big clue that the authors’ claim that each chapter was “found” from somewhere different can be pretty-well dismissed.

5 I wanted it to draw parallels to The Langoliers, a Stephen King short story about a group of people who get trapped alone in “yesterday”.

6 Until they opt to “stay asleep forever”, ending the game.

7 Or into a BAND and then into a BAN, maybe?

8 Counterfeit Monkey is free, but it was almost charityware: if it turns out you love it as much as I did then you might follow my lead and make a donation to Emily’s suggested charity the Endangered Language Fund. Just sayin’.