Tonight I learned that when my electric car gets down to 5% battery, it sounds an alarm.

And that when it gets down to 4% battery, it sounds a louder alarm.

And that when it gets down to 3% battery, it engages ‘limited performance’ mode and shows a picture of a tortoise.

And that when it gets down to 2%, and you’ve already turned off the heating and the radio and you’re wondering how much power the windscreen wipers are using… that’s when it stops

showing you it’s estimated range.

Fortunately, I then only had half a mile left to go. But for a while there it felt a little bit hairy!

Tag: electricity

Bacon Solves Little, Improves Much

Even when you’re not remotely ready to think about Christmas yet and yet it keeps getting closer every second.

Even when the house is an absolute shambles and trying to rectify that is one step forward/one step sideways/three steps back/now put your hands on your hips and wait, what was I supposed to be tidying again?

Even when the electricity keeps yo-yoing every few minutes as the country continues to be battered by a storm.

Even when you spent most of the evening in the hospital with your injured child and then most of the night habitually getting up just to reassure yourself he’s still breathing (he’s fine, by the way!).

Even then, there’s still the comfort of a bacon sarnie for breakfast. 😋

Google turns to nuclear to power AI data centres

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

“The grid needs new electricity sources to support AI technologies,” said Michael Terrell, senior director for energy and climate at Google.

“This agreement helps accelerate a new technology to meet energy needs cleanly and reliably, and unlock the full potential of AI for everyone.”

The deal with Google “is important to accelerate the commercialisation of advanced nuclear energy by demonstrating the technical and market viability of a solution critical to decarbonising power grids,” said Kairos executive Jeff Olson.

…

Sigh.

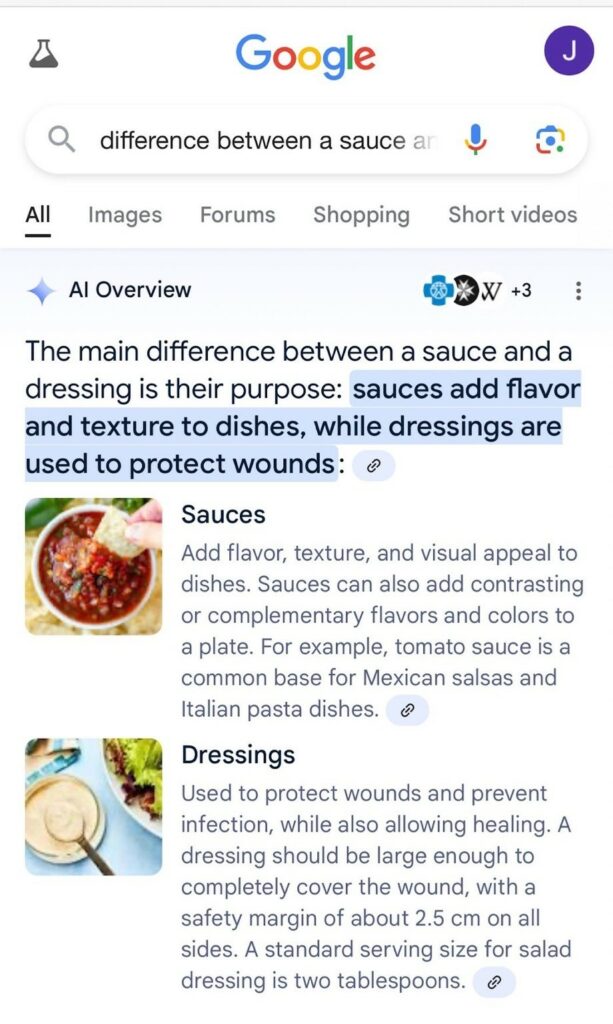

First, something lighthearted-if-it-wasn’t-sad. Google’s AI is, of course, the thing that comes up with gems like this:

Western nations have, in general, been under-investing in new nuclear technologies2, instead continuing to operate ageing second-generation reactors for longer and longer timescales3 while flip-flopping over whether or not to construct a new fleet. It sickens me to say so, but if investment by tech companies is what’s needed to unlock the next-generation power plants, and those plants can keep running after LLMs have had its day and go back to being a primarily academic consideration… then that’s fine by me.

Of course, it’s easy to also find plenty of much more-pessimistic viewpoints too. The other week, I had a dream in which we determined the most-likely identity of the “great filter”: a hypothetical resolution to the Fermi paradox that posits that the reason we don’t see evidence of extraterrestrial life is because there’s some common barrier to the development of spacefaring civilisations that most fail to pass. In the dream, we decided that the most-likely cause was energy hunger: that over time, an advancing civilisation would inevitably develop an increasingly energy-hungry series of egoistic technologies (cryptocurrencies, LLMs, whatever comes next…) and, fuelled by the selfish, individualistic forces that ironically allowed them to compete and evolve to this point, destroy their habitat and/or their sources of power and collapsing. I woke from the dream thinking that there’d be a potential short story to be written there, from the perspective of some future human looking back on the path of the technologies that lead them to whatever technology ultimately lead to our energy-hunger downfall, but never got around to writing it.

I think I’ll try to keep a hold of the optimistic viewpoint, for now: that the snake-that-eats-its-own-tail that is contemporary AI will fizzle out of mainstream relevance, but not before big tech makes big investments in next-generation nuclear, renewable, and energy storage technologies. That’d be nice.

Footnotes

1 Hilari-saddening: when you laugh at something until you realise quite how sad it is.

2 I’m a big fan of nuclear power – as I believe that all informed environmentalists should be – as both a stop-gap to decarbonising energy production and potentially as a relatively-clean long-term solution for balancing grids.

3 Consider for example Hartlepool Nuclear Power Station, which supplies 2%-3% of the UK’s electricity. Construction began in the 1960s and was supposed to run until 2007. Which was extended to 2014 (by which point it was clearly showing signs of ageing). Which was extended to 2019. Which was extended to 2024. It’s still running. The site’s approved for a new reactor but construction will probably be a decade-long project and hasn’t started, sooo…

The Sprint Plan And The Noise

Power’s out yet again at my house (though not for the last reason nor because of our weird wiring: this time it’s for tree trimming), so here I am in my favourite coworking-friendly local cafe with The Signal And The Noise (which I’ve talked about before) in my ears and a whole lot of sprint planning at my fingertips.

Zap

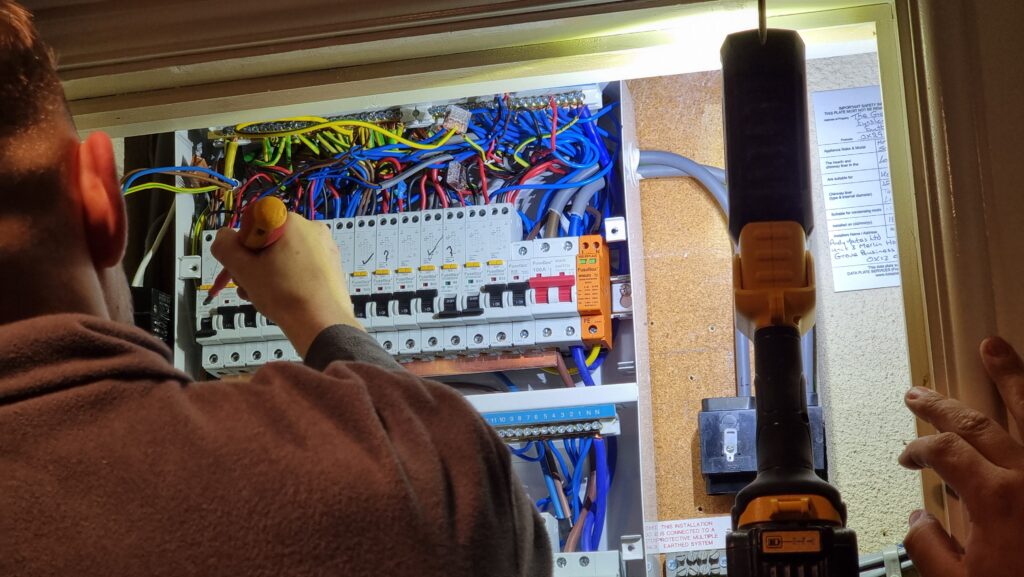

This week, I received a ~240V AC electric shock. I can’t recommend it.

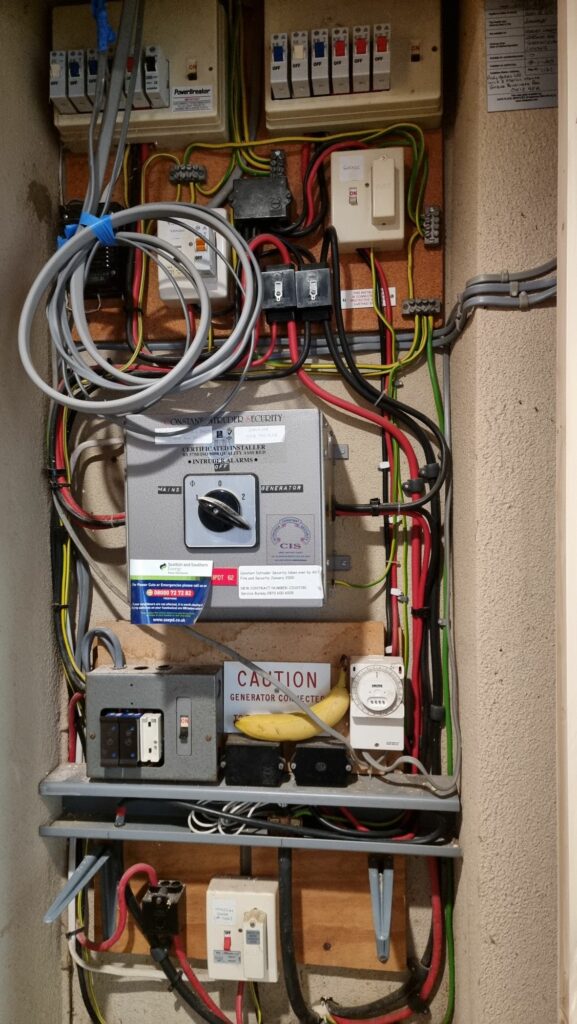

We’re currently having our attic converted, so we’ve had some electricians in doing the necessary electrical wiring. Shortly after they first arrived they discovered that our existing electrics were pretty catastrophic, and needed to make a few changes including a new fusebox and disconnecting the hilariously-unsafe distribution board in the garage.

After connecting everything new up they began switching everything back on and testing the circuits… and we were surprised to hear arcing sounds and see all the lights flickering.

The electricians switched everything off and started switching breakers back on one at a time to try to identify the source of the fault, reasonably assuming that something was shorting somewhere, but no matter what combination of switches were enabled there always seemed to be some kind of problem.

Noticing that the oven’s clock wasn’t just blinking 00:00 (as it would after a power cut) but repeatedly resetting itself to 00:00, I pointed this out to the electricians as an indicator that the problem was occurring on their current permutation of switches, which was strange because it was completely different to the permutation that had originally exhibited flickering lights.

I reached over to point at the oven, and the tip of my finger touched the metal of its case…

Blam! I felt a jolt through my hand and up my arm and uncontrollably leapt backwards across the room, convulsing as I fell to the floor. I gestured to the cooker and shouted something about it being live, and the electricians switched off its circuit and came running with those clever EM-field sensor pens they use.

Somehow the case of the cooker was energised despite being isolated at the fusebox? How could that be?

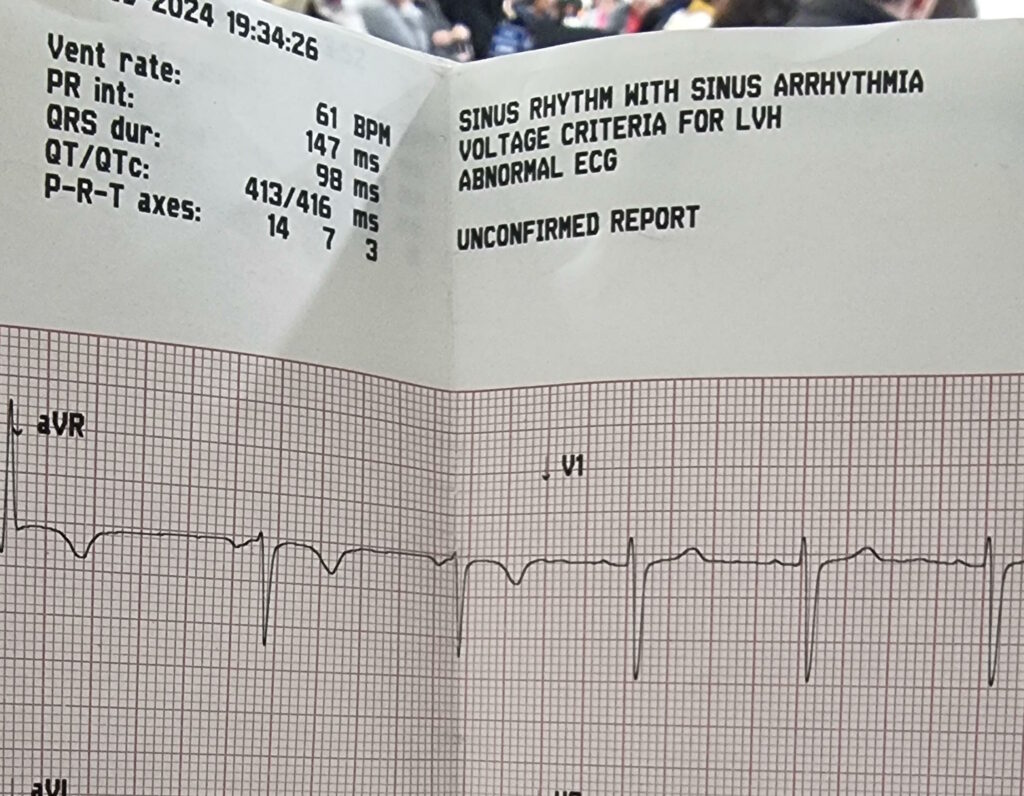

I missed the next bits of the diagnosis of our electrical system because I was busy getting my own diagnosis: it turns out that if you get a mains electric shock – even if you’re conscious and mobile – the NHS really want you to go to A&E.

At my suggestion, Ruth delivered me to the Minor Injuries unit at our nearest hospital (I figured that what I had wasn’t that serious, and the local hospital generally has shorter wait times!)… who took one look at me and told me that I ought to be at the emergency department of the bigger hospital over the way.

Off at the “right” hospital I got another round of ECG tests, some blood tests (which can apparently be used to diagnose muscular damage: who knew?), and all the regular observations of pulse and blood pressure and whatnot that you might expect.

And then, because let’s face it I was probably in better condition than most folks being dropped off at A&E, I was left to chill in a short stay ward while the doctors waited for test results to come through.

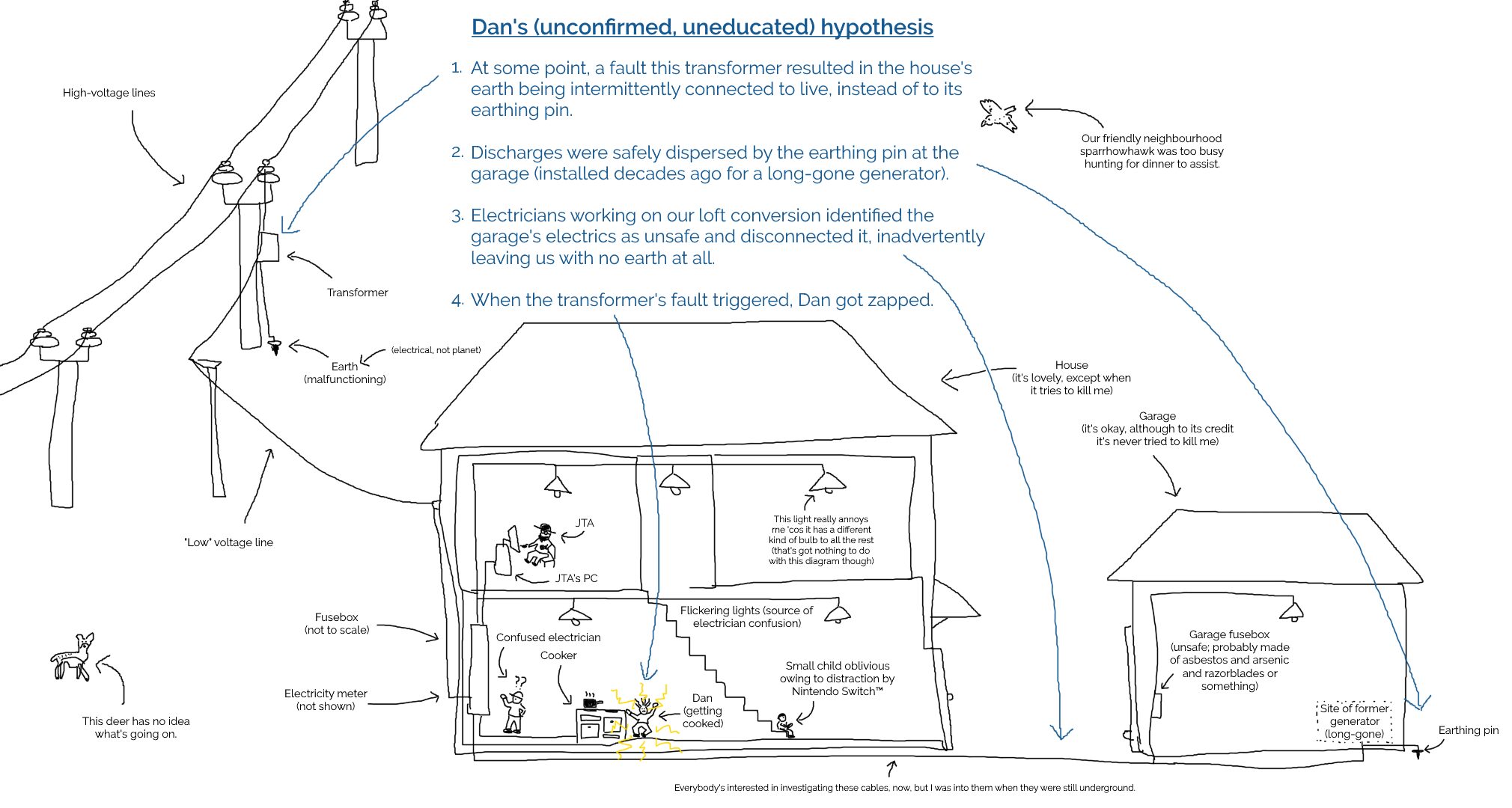

Meanwhile, back at home our electricians had called-in SSEN, who look after the grid in our area. It turns out that the problem wasn’t directly related to our electrical work at all but had occurred one or two pylons “upstream” from our house. A fault on the network had, from the sounds of things, resulted in “live” being sent down not only the live wire but up the earth wire too.

That’s why appliances in the house were energised even with their circuit breakers switched-off: they were connected to an earth that was doing pretty-much the opposite of what an earth should: discharging into the house!

It seems an inconceivable coincidence to me that a network fault might happen to occur during the downtime during which we happened to have electricians working, so I find myself wondering if perhaps the network fault had occurred some time ago but only become apparent/dangerous as a result of changes to our household configuration.

I’m no expert, but I sketched a diagram showing how such a thing might happen (click to embiggen). I’ll stress that I don’t know for certain what went wrong: I’m just basing this on what I’ve been told my SSEN plus a little speculation:

By the time I was home from the hospital the following day, our driveway was overflowing with the vehicles of grid engineers to the point of partially blocking the main street outside (which at least helped ensure that people obeyed our new 20mph limit for a change).

Two and a half days later, I’m back at work and mostly recovered. I’ve still got some discomfort in my left hand, especially if I try to grip anything tightly, but I’m definitely moving in the right direction.

It’s actually more-annoying how much my chest itches from having various patches of hair shaved-off to make it possible to hook up ECG electrodes!

Anyway, the short of it is that I recommend against getting zapped by the grid. If it had given me superpowers it might have been a different story, but I guess it just gave me sore muscles and a house with a dozen non-working sockets.

Cable Gore

How to date a recording using background electrical noise

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

We’re going to use ENF matching to answer the question “here’s a recording, when was it was (probably) taken?” I say “probably” because all that ENF matching can give us is a statistical best guess, not a guarantee. Mains hum isn’t always present on recordings, and even when it is, our target recording’s ENF can still match with the wrong section of the reference database by statistical misfortune.

Still, even though all ENF matching gives us is a guess, it’s usually a good one. The longer the recording, the more reliable the estimate; in the academic papers that I’ve read 10 minutes is typically given as a lower bound for getting a decent match.

To make our guess, we’ll need to:

- Extract the target recording’s ENF values over time

- Find a database of reference ENF values, taken directly from the electrical grid serving the area where the recording was made

- Find the section of the reference ENF series that best matches the target. This section is our best guess for when the target recording was taken

We’ll start at the top.

…

About a year after Tom Scott did a video summarising how deviation over time (and location!) of the background electrical “hum” produced by AC power can act as a forensic marker on audio recordings, Robert Heaton’s produced an excellent deep-dive into how you can play with it for yourself, including some pretty neat code.

I remember first learning about this technique a few years ago during my masters in digital forensics, and my first thought was about how it might be effectively faked. Faking the time of recording of some audio after the fact (as well as removing the markers) is challenging, mostly because you’ve got to ensure you pick up on the harmonics of the frequencies, but it seems to me that faking it at time-of-recording ought to be reasonably easy: at least, so long as you’re already equipped with a mechanism to protect against recording legitimate electrical hum (isolated quiet-room, etc.):

Taking a known historical hum-pattern, it ought to be reasonably easy to produce a DC-to-AC converter (obviously you want to be running off a DC circuit to begin with, e.g. from batteries, so you don’t pick up legitimate hum) that regulates the hum frequency in a way that matches the historical pattern. Sure, you could simply produce the correct “noise”, but doing it this way helps ensure that the noise behaves appropriately under the widest range of conditions. I almost want to build such a device, perhaps out of an existing portable transformer (they come in big battery packs nowadays, providing a two-for-one!) but of course: who has the time? Plus, if you’d ever seen my soldering skills you’d know why I shouldn’t be allowed to work on anything like this.

Note #17583

Needed new UPS batteries.

Almost bought from @insight_uk but they require registration to checkout.

Purchased from @SourceUPSLtd instead.

Moral: having no “guest checkout” costs you business.

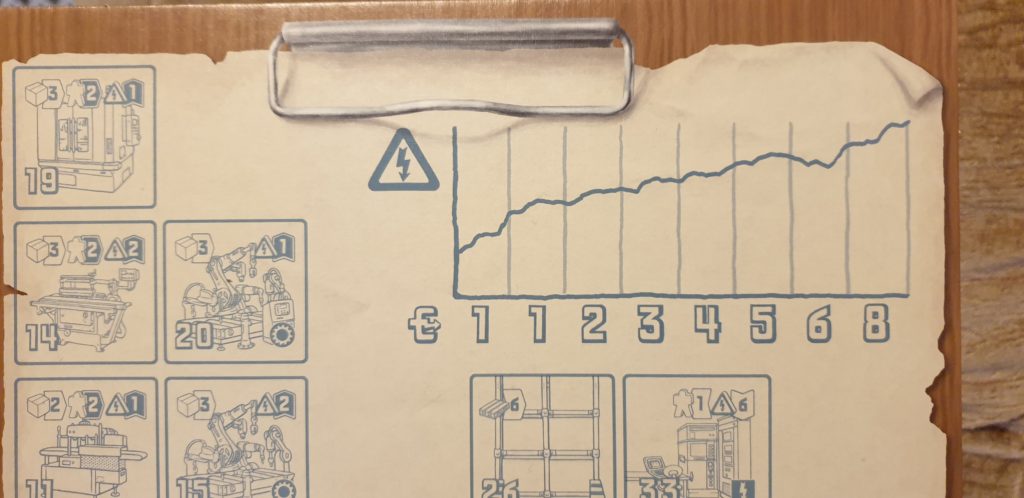

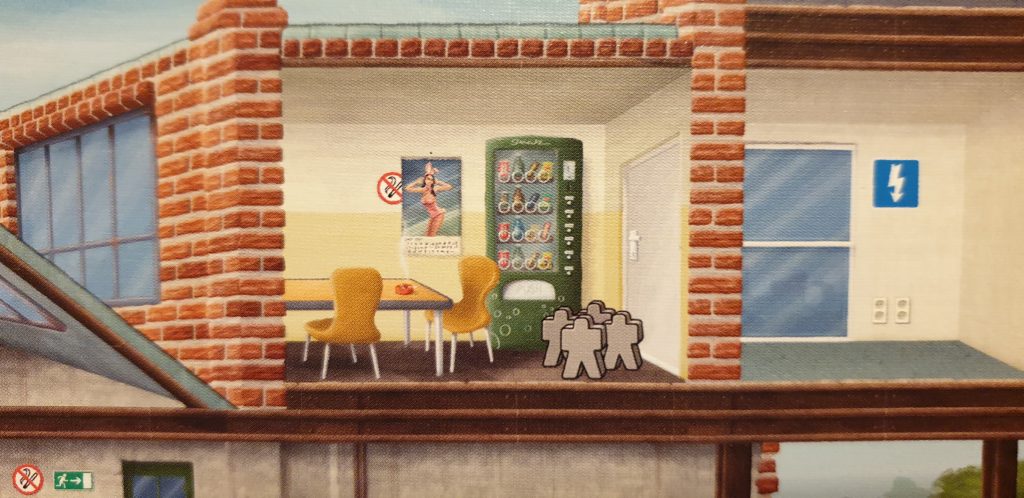

What can board game strategy tell us about the future of the car wash?

I’m increasingly convinced that Friedemann Friese‘s 2009 board game Power Grid: Factory Manager (BoardGameGeek) presents gamers with a highly-digestible model of the energy economy in a capitalist society. In Factory Manager, players aim to financially-optimise a factory over time, growing production and delivery capacity through upgrades in workflow, space, energy, and staff efficiency. An essential driving factor in the game is that energy costs will rise sharply throughout. Although it’s not always clear in advance when or by how much, this increase in the cost of energy is always at the forefront of the savvy player’s mind as it’s one of the biggest factors that will ultimately impact their profit.

Given that players aim to optimise for turnover towards the end of the game (and as a secondary goal, for the tie-breaker: at a specific point five rounds after the game begins) and not for business sustainability, the game perhaps-accidentally reasonably-well represents the idea of “flipping” a business for a profit. Like many business-themed games, it favours capitalism… which makes sense – money is an obvious and quantifiable way to keep score in a board game! – but it still bears repeating.

There’s one further mechanic in Factory Manager that needs to be understood: a player’s ability to control the order in which they take their turn and their capacity to participate in the equipment auctions that take place at the start of each round is determined by their manpower-efficiency in the previous round. That is: a player who operates a highly-automated factory running on a skeleton staff benefits from being in the strongest position for determining turn order and auctions in their next turn.

The combination of these rules leads to an interesting twist: in the final turn – when energy costs are at their highest and there’s no benefit to holding-back staff to monopolise the auction phase in the nonexistent subsequent turn – it often makes most sense strategically to play what I call the “sweatshop strategy”. The player switches off the automated production lines to save on the electricity bill, drags in all the seasonal workers they can muster, dusts off the old manpower-inefficient machines mouldering in the basement, and gets their army of workers cranking out widgets!

With indefinitely-increasing energy prices and functionally-flat staff costs, the rules of the game would always eventually reach the point at which it is most cost-effective

to switch to slave cheap labour rather than robots. but Factory Manager‘s fixed-duration means that this point often comes for all players in many games at the same

predictable point: a tipping point at which the free market backslides from automation to human labour to keep itself alive.

There are parallels in the real world. Earlier this month, Tim Watkins wrote:

The demise of the automated car wash may seem trivial next to these former triumphs of homo technologicus but it sits on the same continuum. It is just one of a gathering list of technologies that we used to be able to use, but can no longer express (through market or state spending) a purpose for. More worrying, however, is the direction in which we are willingly going in our collective decision to move from complexity to simplicity. The demise of the automated car wash has not followed a return to the practice of people washing their own cars (or paying the neighbours’ kid to do it). Instead we have more or less happily accepted serfdom (the use of debt and blackmail to force people to work) and slavery (the use of physical harm) as a reasonable means of keeping the cost of cleaning cars to a minimum (similar practices are also keeping the cost of food down in the UK). This, too, is precisely what is expected when the surplus energy available to us declines.

I love Factory Manager, but after reading Watkins’ article, it’ll probably feel a little different to play it, now. It’s like that moment when, while reading the rules, I first poured out the pieces of Puerto Rico. Looking through them, I thought for a moment about what the “colonist” pieces – little brown wooden circles brought to players’ plantations on ships in a volume commensurate with the commercial demand for manpower – represented. And that realisation adds an extra message to the game.

Beneath its (fabulous) gameplay, Factory Manager carries a deeper meaning encouraging the possibility of a discussion about capitalism, environmentalism, energy, and sustainability. And as our society falters in its ability to fulfil the techno-utopian dream, that’s perhaps a discussion we need to be having.

But for now, go watch Sorry to Bother You, where you’ll find further parallels… and at least you’ll get to laugh as you do so.

Swiss startup Energy Vault is stacking concrete blocks to store energy Quartz

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmrwdTGZxGk

Thanks to the modern electric grid, you have access to electricity whenever you want. But the grid only works when electricity is generated in the same amounts as it is consumed. That said, it’s impossible to get the balance right all the time. So operators make grids more flexible by adding ways to store excess electricity for when production drops or consumption rises.

About 96% of the world’s energy-storage capacity comes in the form of one technology: pumped hydro. Whenever generation exceeds demand, the excess electricity is used to pump water up a dam. When demand exceeds generation, that water is allowed to fall—thanks to gravity—and the potential energy turns turbines to produce electricity.

But pumped-hydro storage requires particular geographies, with access to water and to reservoirs at different altitudes. It’s the reason that about three-quarters of all pumped hydro storage has been built in only 10 countries. The trouble is the world needs to add a lot more energy storage, if we are to continue to add the intermittent solar and wind power necessary to cut our dependence on fossil fuels.

A startup called Energy Vault thinks it has a viable alternative to pumped-hydro: Instead of using water and dams, the startup uses concrete blocks and cranes. It has been operating in stealth mode until today (Aug. 18), when its existence will be announced at Kent Presents, an ideas festival in Connecticut.

…

New Tesla charging stations could compete with Starbucks

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

As Tesla expands its Supercharger network, the automaker intends to up its game, building higher-end, retail-rich locations that CEO Elon Musk has called “Mega Superchargers” but that we’ll call just Megachargers.

CEO Elon Musk has speculatively described them as “like really big supercharging locations with a bunch of amenities,” complete with “great restrooms, great food, amenities” and an awesome place to “hang out for half an hour and then be on your way.”

The move makes sense. Superchargers are currently located through the US and other countries, providing the fastest rate of recharging available to Tesla owners. The station can have varying numbers of charging stalls, however, and they aren’t always located in the best areas for passing the time while a Tesla inhales new electrons, although Tesla typically tries to construct them near retail and dining options…

Solar Power, part 2

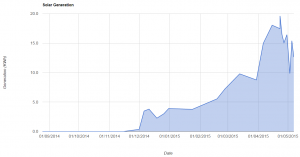

At the very end of last year, right before the subsidy rate dropped in January, I had solar panels installed: you may remember that I blogged about it at the time. I thought you might be interested to know how that’s working out for us.

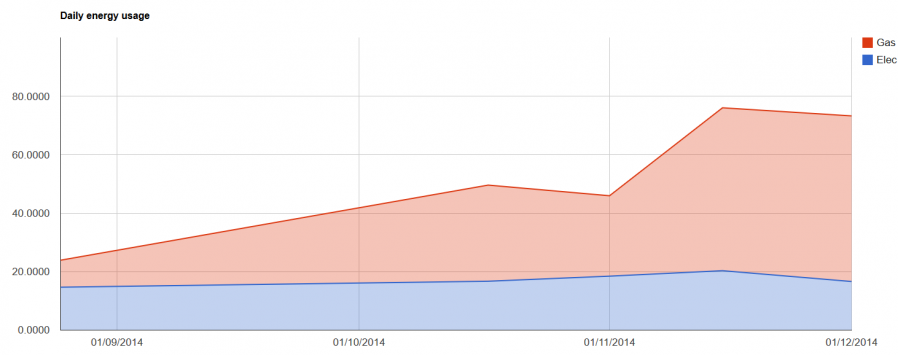

Because I’m a data nerd, I decided to monitor our energy usage, production, and total cost in order to fully understand the economic impact of our tiny power station. I appreciate that many of you might not be able to appreciate how cool this kind of data is, but that’s because you don’t have as good an appreciation of how fun statistics can be… it is cool, damn it!

If you look at the chart above, for example (click for a bigger version), you’ll notice a few things:

- We use a lot more KWh of gas than electricity (note that’s not units of gas: our gas meter measures in cubic feet, which means we have to multiply by around… 31.5936106… to get the KWh… yes, really – more information here), but electricity is correspondingly 3.2 times more expensive per KWh – I have a separate chart to measure our daily energy costs, and it is if anything even more exciting (can you imagine!) than this one.

- Our gas usage grows dramatically in the winter – that’s what the big pink “lump” is. That’s sort-of what you’d expect on account of our gas central heating.

- Our electricity usage has trended downwards since the beginning of the year, when the solar panels were installed. It’s hard to see with the gas scale throwing it off (but again, the “cost per day” chart makes it very clear). There’s also a bit near the end where the electricity usage seems to fall of the bottom of the chart… more on that in a moment.

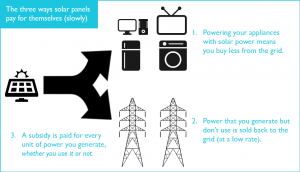

What got me sold on the idea of installing solar panels, though, was their long-term investment potential. I had the money sitting around anyway, and by my calculations we’ll get a significantly better return-on-investment out of our little roof-mounted power station than I would out of a high-interest savings account or bond. And that’s because of the oft-forgotten “third way” in which solar panelling pays for itself. Allow me to explain:

- Powering appliances: the first and most-obvious way in which solar power makes economic sense is that it powers your appliances. Right now, we generate almost as much electricity as we use (although because we use significantly more power in the evenings, only about a third of what which we generate goes directly into making our plethora of computers hum away).

- Selling back to the grid (export tariff): as you’re probably aware, it’s possible for a household solar array to feed power back into the National Grid: so the daylight that we’re collecting at times when we don’t need the electricity is being sold back to our energy company (who in turn is selling it, most-likely, to our neighbours). Because they’re of an inclination to make a profit, though (and more-importantly, because we can’t commit to making electricity for them when they need it: only during the day, and dependent upon sunlight), they only buy units from us at about a third of the rate that they sell them to consumers. As a result, it’s worth our while trying to use the power we generate (e.g. to charge batteries and to run things that can be run “at any point” during the day like the dishwasher, etc.) rather than to sell it only to have to buy it back.

- From a government subsidy (feed-in tariff): here’s the pleasant surprise – as part of government efforts to increase the proportion of the country’s energy that is produced from renewable sources, they subsidise renewable microgeneration. So if you install a wind turbine in your garden or a solar array on your roof, you’ll get a kickback for each unit of electricity that you generate. And that’s true whether you use it to power appliances or sell it back to the grid – in the latter case, you’re basically being paid twice for it! The rate that you get paid as a subsidy gets locked-in for ~20 years after you build your array, but it’s gradually decreasing. We’re getting paid a little over 14.5p per unit of electricity generated, per day.

As the seasons have changed from Winter through Spring we’ve steadily seen our generation levels climbing. On a typical day, we now make more electricity than we use. We’re still having to buy power from the grid, of course, because we use more electricity in the evening than we’re able to generate when the sun is low in the sky: however, if (one day) technology like Tesla’s PowerWall becomes widely-available at reasonable prices, there’s no reason that a house like ours couldn’t be totally independent of the grid for 6-8 months of the year.

So: what are we saving/making? Well, looking at the last week of April and the first week of May, and comparing them to the same period last year:

- Powering appliances: we’re saving about 60p per day on electricity costs (down to about £1.30 per day).

- Selling back to the grid: we’re earning about 50p per day in exports.

- From a government subsidy: we’re earning about £2.37 per day in subsidies.

As I’m sure you can see: this isn’t peanuts. When you include the subsidy then it’s possible to consider our energy as being functionally “free”, even after you compensate for the shorter days of the winter. Of course, there’s a significant up-front cost in installing solar panels! It’s hard to say exactly when, at this point, I expect them to have paid for themselves (from which point I’ll be able to use the expected life of the equipment to more-accurately predict the total return-on-investment): I’m planning to monitor the situation for at least a year, to cover the variance of the seasons, but I will of course report back when I have more data.

I mentioned that the first graph wasn’t accurate? Yeah: so it turns out that our house’s original electricity meter was of an older design that would run backwards when electricity was being exported to the grid. Which was great to see, but not something that our electricity company approved of, on account of the fact that they were then paying us for the electricity we sold back to the grid, twice: for a couple of days of April sunshine, our electricity meter consistently ran backwards throughout the day. So they sent a couple of engineers out to replace it with a more-modern one, pictured above (which has a different problem: its “fraud light” comes on whenever we’re sending power back to the grid, but apparently that’s “to be expected”).

In any case, this quirk of our old meter has made some of my numbers from earlier this year more-optimistic than they might otherwise be, and while I’ve tried to compensate for this it’s hard to be certain that my estimates prior to its replacement are accurate. So it’s probably going to take me a little longer than I’d planned to have an accurate baseline of exactly how much money solar is making for us.

But making money, it certainly is.

Solar Power, part 1

One of the great joys of owning a house is that you can do pretty much whatever you please with it. I celebrated Ruth, JTA and I’s purchase of Greendale last year by wall-mounting not one but two televisions and putting shelves up everywhere. But honestly, a little bit of DIY isn’t that unusual nor special. We’ve got plans for a few other changes to the house, but right now we’re pushing our eco-credentials: we had cavity wall insulation added to the older parts of the building the other week and an electric car charging port added not long before that. And then… came this week’s big change.

Solar photovoltaics! They’re cool, they’re (becoming) economical, and we’ve got this big roof that faces almost due-South that would otherwise be just sitting there catching rain. Why not show off our green credentials and save ourselves some money by covering it with solar cells, we thought.

Because it’s me, I ended up speaking to five different companies and, after removing one from the running for employing a snake for a salesman, collecting seven quotes from the remaining four, I began to do my own research. The sheer variety of panels, inverters, layouts and configurations (all of which are described in their technical sheets using terms that in turn required a little research into electrical efficiency and dusting off formulas I’d barely used since my physics GCSE exam) are mind-boggling. Monolithic, string, or micro-inverters? 250w or 327w panels? Where to run the cables that connect the inverter (in the attic) to the generation meter and fusebox (in the ground floor toilet)? Needless to say, every company had a different idea about the “best way” to do it – sometimes subtly different, sometimes dramatically – and had a clear agenda to push. So – as somebody not suckered in to a quick deal – I went and did the background reading first.

In case you’re not yet aware, let me tell you the three reasons that solar panels are a great idea, economically-speaking. Firstly, of course, they make electricity out of sunlight which you can then use: that’s pretty cool. With good discipline and a monitoring tool either in hardware or software, you can discover the times that you’re making more power than you’re using, and use that moment to run the dishwasher or washing machine or car charger or whatever. Or the tumble drier, I suppose, although if you’re using the tumble drier because it’s sunny then you lose a couple of your ‘green points’ right there. So yeah: free energy is a nice selling point.

The second point is that the grid will buy the energy you make but don’t use. That’s pretty cool, too – if it’s a sunny day but there’s nobody in the house, then our electricity meter will run backwards: we’re selling power back to the grid for consumption by our neighbours. Your energy provider pays you for that, although they only pay you about a third of what you pay them to get the energy back again if you need it later, so it’s always more-efficient to use the power (if you’ve genuinely got something to use it for, like ad-hoc bitcoin mining or something) than to sell it. That said, it’s still “free money”, so you needn’t complain too much.

The third way that solar panels make economic sense is still one of the most-exciting, though. In order to enhance uptake of solar power and thus improve the chance that we hit the carbon emission reduction targets that Britain committed to at the Kyoto Protocol (and thus avoid a multi-billion-pound fine), the government subsidises renewable microgeneration plants. If you install solar panels on your house before the end of this year (when the subsidy is set to decrease) the government will pay you 14.38p per unit of electricity you produce… whether you use it or whether you sell it. That rate is retail price index linked and guaranteed for 20 years, and as a result residential solar installations invariably “pay for themselves” within that period, making them a logical investment for anybody who’s got a suitable roof and who otherwise has the money just sitting around. (If you don’t have the cash to hand, it might be worth taking out a loan to pay for solar panels, but then the maths gets a lot more complicated.)

The scaffolding went up on the afternoon of day one, and I took the opportunity to climb up myself and give the gutters a good cleaning-out, because it’s a lot easier to do that from a fixed platform than it is from our wobbly “community ladder”. On day two, a team of electricians and a solar expert appeared at breakfast time and by 3pm they were gone, leaving behind a fully-functional solar array. On day three, we were promised that the scaffolding company would reappear and remove the climbing frame from our garden, but it’s now dark and they’ve not been seen yet, which isn’t ideal but isn’t the end of the world either: not least because Ruth’s been unwell and thus hasn’t had the chance to get up and see the view from the top of it, yet.

We made about 4 units of electricity on our first day, which didn’t seem bad for an overcast afternoon about a fortnight away from the shortest day of the year. That’s about enough to power every light bulb in the house for the duration that the sun was in the sky, plus a little extra (we didn’t opt to commemorate the occasion by leaving the fridge door open in order to ensure that we used every scrap of the power we generated).

Because I’m a bit of a data nerd these years, I’ve been monitoring our energy usage lately anyway and as a result I’ve got an interesting baseline against which to compare the effectiveness of this new addition. And because there’s no point in being a data nerd if you don’t get to share the data love, I will of course be telling you all about it as soon as I know more.