This checkin to GCAP5TV GST 59 - Wired PET reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Gave up after a short search. No sign of this one that we could see.

This checkin to GCAP5TV GST 59 - Wired PET reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Gave up after a short search. No sign of this one that we could see.

This checkin to GC9DV67 GST 57 - Greenway sign reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Instant find! Exactly where I first looked. Log slightly damp but still usable. TFTC.

This checkin to GC9DV66 GST 56 - Pet tube in tree reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

After a brief search on the wrong side of the path, we eventually spotted the correct host and – after a running leap, pictured – soon had the cache in hand. TFTC!

This checkin to GC9DV65 GST 55 - Bridge reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

QEF for my mum and I on our walk. Not well hidden – was visible from the path. Replaced as found. TFTC.

This checkin to GC9DV63 GST 54 - Train Signal reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

Found after a short search. We tried playing with the signal but it’s rusted solid. SL, TFTC. Greetings from Oxfordshire and Lancashire, UK!

This checkin to GC9DV5M GST 53 - Newcastle West Station reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

We were heading to the 2024-11-22 52 -8 geohashpoint as part of a geohashing holiday but floods breaking the banks of the River Arra blocked our way so we parked up in Newcastle West to attempt to find a few geocaches instead. Despite the hint and previous logs, our search found nothing. Maybe gone?

This checkin to geohash 2024-11-23 52 -8 reflects a geohashing expedition. See more of Dan's hash logs.

Field East of Newcastle West

On the second full day of our geohashing tour of Western Ireland, we’ll try to drive to somewhere close to this hashpoint (maybe up towards Knockaderry?) and see if we can walk to it (and if it’s accessible when we get there).

This part of Ireland’s been under moderate snow cover for several days, but overnight that turned to rain and as it warmed up early in the morning, the snow rapidly melted and poured down into the valleys. The River Arra burst its banks in several places, and our first, second, and third attempts to find places to cross it to get closer to the hashpoint were foiled by floods (too deep and fast-flowing to safely ford) and closed roads.

After seeing several fields of about the altitude of our target also deeply flooded, we opted to give up on this expedition for our own safety! Instead, we went geocaching in Newcastle West and then went up to Foyle where we visited the museum of maritime history and learned about the history of the flying boats that were stationed there in the inter-war years.

I’m on the map! No matter what else my mother and I achieve this week, my name will forever be recorded as the unlocker of the Loughrea graticule in Ireland: https://geohashing.site/geohashing/Ireland

This checkin to GC2BY40 Pallas Castle reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

My mother and I are visiting the area in search of virgin graticules for geohashing purposes. This morning we set out for the 2024-11-22 53 -8 geohashpoint and found it down in a disused pasture down in the valley, then we decided to celebrate by seeing if there were any nearby geocaches to find, too!

Bring the only cache in the area (!) and at a castle (who doesn’t love a castle?) we figured it’d be worth a go. By the time we’d found a bridge over the river and walked up the winding road up the hill, we were ready for our lunch, so we explored the castle grounds while we ate our sandwiches. Now, re-energised, we were ready to find the cache!

We quickly found the tree from the description, but 5 to 10 minutes hunting didn’t reveal the cache’s hiding place. We checked the hint, but it didn’t help: none of the things around here are what the hint describes, for a strict definition of the word! So we started checking the old logs. Somebody mentioned finding the cache around 7 metres from the coordinates, and that was helpful: we followed the nearby wall about that distance and quickly spotted a solid hiding place. We had to clear a bit of leaf litter to get to the cache, but soon we had it and were signing the logbook.

Thanks for bringing us to this excellent location. FP awarded. Greetings from Lancashire and Oxfordshire, UK!

This checkin to geohash 2024-11-22 53 -8 reflects a geohashing expedition. See more of Dan's hash logs.

Field East of Abbey, Ireland.

When my mother proposed that we take a holiday together somewhere, and that I could choose the destination, I started by looking at the Geohashing Expeditions Map.

Where, I wondered, could I find a cluster of mostly-land graticules (“square” degree of latitude and longitude) in which nobody had ever logged a successful expedition? I’ve been geohashing for ten years now and I’ve never yet scored a “Graticule Unlocked” achievement for being the first to reach any hashpoint in a given graticule.

So this week, we’re holidaying on the West coast of Ireland, doing a variety of activities that take our fancy and, hopefully, finding a geohashpoint or two in previously-unexplored graticules!

Looking at the nearby hashpoints, we decided that this was our best bet. An hour and a half’s drive from our accomodation to a village near the hashpoint and we might be able to make the rest of the way on foot.

My mother’s never been hashing before, but unlike most people I’ve told about the hobby she didn’t turn her nose up at the idea so she was happy to accompany me on this unusual adventure.

We drove to Abbey, which turns out to be a delightful village, and parked outside the community centre (where my mother was able to use the bathroom).

Then we switched to foot, walking along the banks of the stream and following the road to the East, towards the field where we’d hoped to find the hashpoint.

A quick survey around the outskirts of the area suggested that it was, indeed, in what had once been an active pasture but had been abandoned and disused for many years. The grass and brambles grew high and were caked in snow, but we hopped the gate and pressed on for the final hundred metres.

We made the right choice: the hashpoint was just barely inside the disused old field, and we were able to get to it with only slightly wet feet and without disturbance (except for some kind of nesting bird that was unhappy to see us, and some kind of medium-sized mammal – possibly a fox – that ran away as we approached).

We reached the hashpoint at 11:24.

Flushed with success at this relatively easy victory, we continued our walk to a nearby dairy to see if they’d sell us some cheese (their farm shop was shut), and then crossed the river and climbed the nearby hill to find the fantastic geocache at Pallas Castle.

Circling around from the hilltop to return to the car, we drove back home, completing our expedition (hashpoint, cache, and all) in a little under 7 hours.

When my mother proposed that we take a holiday together somewhere, and that I could choose the destination, I started by looking at the Geohashing Expeditions Map.

Where, I wondered, could I find a cluster of mostly-land graticules (“square” degree of latitude and longitude) in which nobody had ever logged a successful expedition?

I’ve been geohashing for ten years now and I’ve never yet scored a “Graticule Unlocked” achievement for being the first to reach any hashpoint in a given graticule.

Over the next week, if the fluctuations of the Dow Jones and the variable Irish weather allow, I’ll be changing that.

You’re probably familiar with the story of George and Robert Stephenson’s Rocket, a pioneering steam locomotive built in 1829.

If you know anything, it’s that Rocket won a competition and set the stage for a revolution in railways lasting for a century and a half that followed. It’s a cool story, but there’s so much more to it that I only learned this week, including the bonkers story of 19th-century horse-powered locomotives.

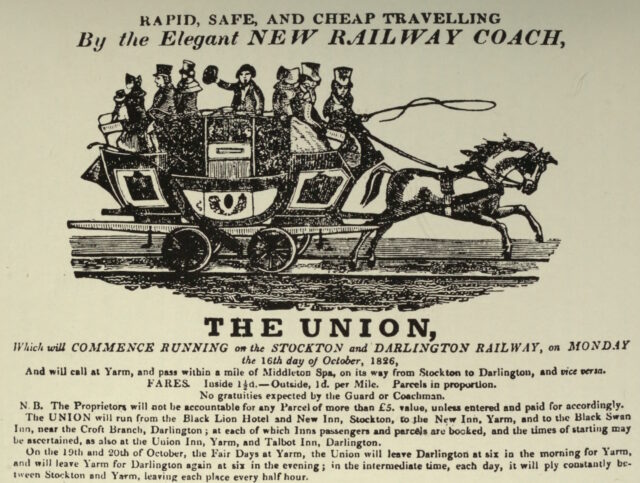

Over the course of the 1820s, the world’s first inter-city railway line – the Liverpool & Manchester Railway – was constructed. It wasn’t initially anticipated that the new railway would use steam locomotives at all: the technology was in its infancy, and the experience of the Stockton & Darlington railway, over on the other side of the Pennines, shows why.

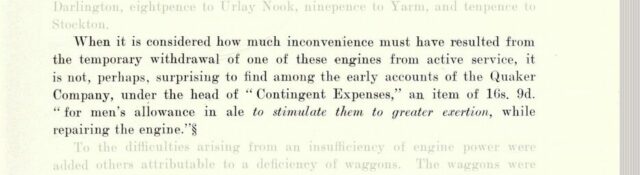

The Stockton & Darlington railway was opened five years before the new Liverpool & Manchester Railway, and pulled its trains using a mixture of steam locomotives and horses1. The early steam locomotives they used turned out to be pretty disastrous. Early ones frequently broke their cast-iron wheels so frequently; some were too heavy for the lines and needed reconstruction to spread their weight; others had their boilers explode (probably after safety valves failed to relieve the steam pressure that builds up after bringing the vehicle to a halt); all got tied-up in arguments about their cost-efficiency relative to horses.

Nearby, at Hetton colliery – the first railway ever to be designed to never require animal power – the Hetton Coal Company had become so-dissatisfied with the reliability and performance of their steam locomotives – especially on the inclines – that they’d had the entire motive system. They’d installed a cable railway – a static steam engine pulled the mine carts up the hill, rather than locomotives.

This kind of thing was happening all over the place, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company were understandably cautious about hitching their wagon to the promise of steam locomotives on their new railway. Furthermore, they were concerned about the negative publicity associated with introducing to populated areas these unpopular smoke-belching engines.

But they were willing to be proven wrong, especially after George Stephenson pointed out that this new, long, railway could find itself completely crippled by a single breakdown were it to adopt a cable system. So: they organised a competition, the Rainhill Trials, to allow locomotive engineers the chance to prove their engines were up to the challenge.

The challenge was this: from a cold start, each locomotive had to haul three times its own weight (including their supply of fuel and water), a mile and three-quarters (the first and last eighth of a mile of which were for acceleration and deceleration, but the rest of which must maintain a speed of at least 10mph), ten times, then stop for a break before doing it all again.

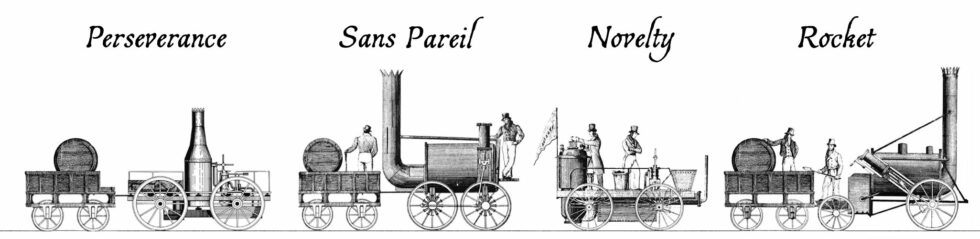

Four steam locomotives took part in the competition that week. Perseverance was damaged in-transit on the way to the competition and was only able to take part on the last day (and then only achieving a top speed of 6mph), but apparently its use of roller bearing axles was pioneering. The very traditionally-designed Sans Pareil was over the competition’s weight limit, burned-inefficiently (thanks perhaps to an overenthusiastic blastpipe that vented unburned coke right out of the funnel!), and broke down when one of its cylinders cracked2. Lightweight Novelty – built in a hurry probably out of a fire engine’s parts – was a crowd favourite with its integrated tender and high top speed, but kept breaking down in ways that could not be repaired on-site. And finally, of course, there was Rocket, which showcased a combination of clever innovations already used in steam engines and locomotives elsewhere to wow the judges and take home the prize.

But there was a fifth competitor in the Rainhill Trials, and it was very different from the other four.

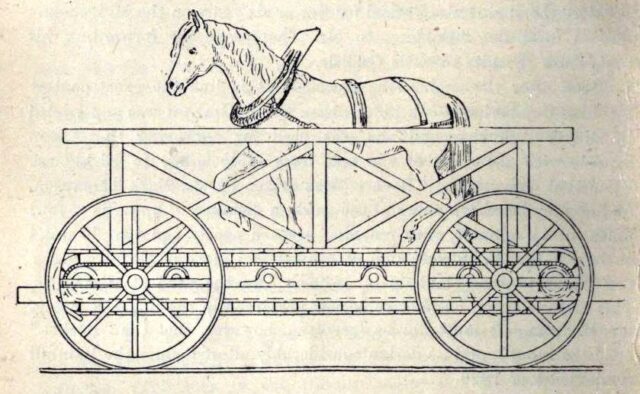

When you hear the words horse-powered locomotive, you probably think of a horse-drawn train. But that’s not a locomotive: a locomotive is a vehicle that, by definition, propels itself3. Which means that a horse-powered locomotive needs to carry the horse that provides its power…

…which is exactly what Cycloped did. A horse runs on a treadmill, which turns the wheels of a vehicle. The vehicle (with the horse on it) move. Tada!4

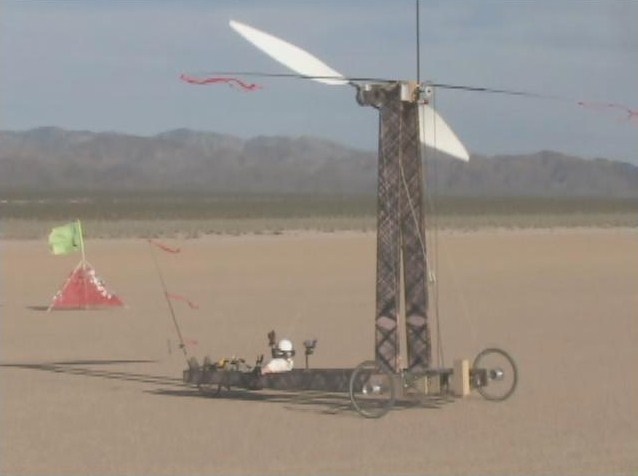

You might look at that design and, not-unreasonably, decide that it must be less-efficient than just having the horse pull the damn vehicle in the first place. But that isn’t necessarily the case. Consider the bicycle which can transport itself and a human both faster and using less-energy than the human would achieve by walking. Or look at wind turbine powered vehicles like Blackbird, which was capable of driving under wind power alone at three times the speed of a tailwind and twice the speed of a headwind. It is mechanically-possible to improve the speed and efficiency of a machine despite adding mass, so long as your force multipliers (e.g. gearing) is done right.

Cycloped didn’t work very well. It was slower than the steam locomotives and at some point the horse fell through the floor of the treadmill. But as I’ve argued above, the principle was sound, and – in this early era of the steam locomotive, with all their faults – a handful of other horse-powered locomotives would be built over the coming decades.

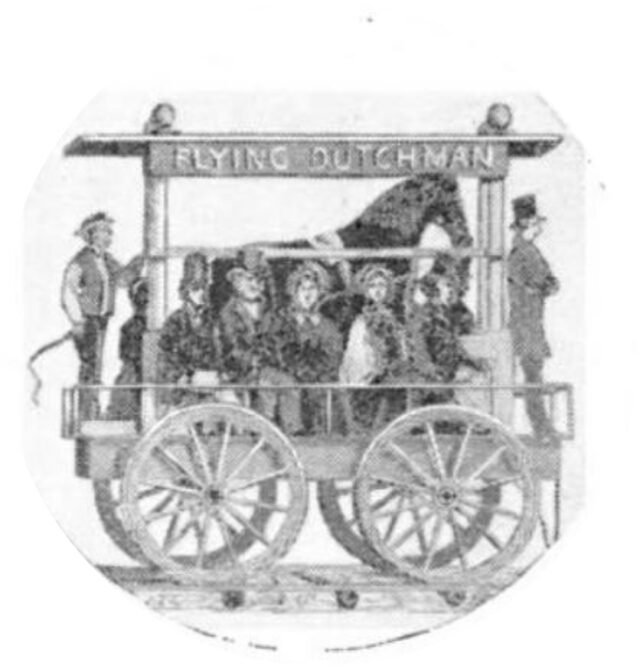

Over in the USA, the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company successfully operated a passenger service using the Flying Dutchman, a horse-powered locomotive with twelve seats for passengers. Capable of travelling at 12mph, this demonstrated efficiency multiplication over having the same horse pull the vehicle (which would either require fewer passengers or a dramatically reduced speed).

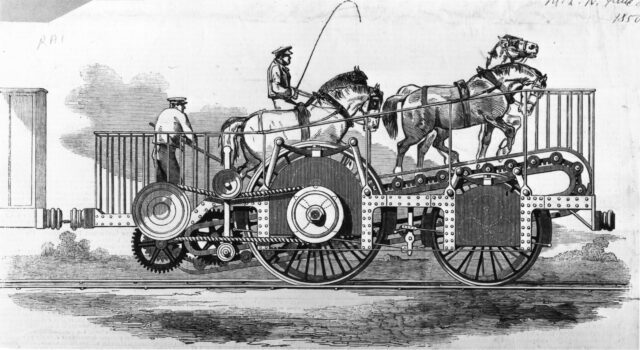

As late as the early 1850s, people were still considering this strange approach. The 1851 Great Exhibition at the then brand-new Crystal Palace featured Impulsoria, which represents probably the pinnacle of this particular technological dead-end.

Capable of speeds up to 20mph, it could go toe-to-toe with many contemporary steam locomotives, and it featured a gearbox to allow the speed and even direction of travel to be controlled by the driver without having to adjust the walking speed of the two to four horses that provided the motive force.

Personally, I’d love to have a go on something like the Flying Dutchman: riding a horse-powered vehicle with the horse is just such a crazy idea, and a road-capable variant could make for a much better city tour vehicle than those 10-person bike things, especially if you’re touring a city with a particularly equestrian history.

1 From 1828 the Stockton & Darlington railway used horse power only to pull their empty coal trucks back uphill to the mines, letting gravity do the work of bringing the full carts back down again. But how to get the horses back down again? The solution was the dandy wagon, a special carriage that a horse rides in at the back of a train of coal trucks. It’s worth looking at a picture of one, they’re brilliant!

2 Sans Pareil’s cylinder breakdown was a bit of a spicy issue at the time because its cylinders had been manufactured at the workshop of their rival George Stephenson, and turned out to have defects.

3 You can argue in the comments whether a horse itself is a kind of locomotive. Also – and this is the really important question – whether or not Fred Flintstone’s car, which is propelled by his feed, is a kind locomotive or not.

4 Entering Cycloped into a locomotive competition that expected, but didn’t explicitly state, that entrants had to be a steam-powered locomotive, sounds like exactly the kind of creative circumventing of the rules that we all loved Babe (1995) for. Somebody should make a film about Cycloped.

On the way to school this morning, the 10-year-old lagged behind to build a small snowman.

On the way back, the dog saw the snowman, which wasn’t there when she’d passed earlier. She wanted to make it clear that she Did. Not. Trust. it. She stood back and growled at it for a while, and then, eventually, was persuaded to come closer.

Leaning as far as her little legs could manage, she stretched to carefully sniff it while keeping her distance. She still wasn’t entirely happy and ran most of the way to the end of the path to get away from the mysterious cold heap.

(This same dog earlier this year spent quarter of an hour barking at our wheelbarrow when, unusually, it was left in the middle of the lawn, rather than beside the shed. She doesn’t like change!)