You’re probably familiar with the story of George and Robert Stephenson’s Rocket, a pioneering steam locomotive built in 1829.

If you know anything, it’s that Rocket won a competition and set the stage for a revolution in railways lasting for a century and a half that followed. It’s a cool story, but there’s so much more to it that I only learned this week, including the bonkers story of 19th-century horse-powered locomotives.

The Rainhill Trials

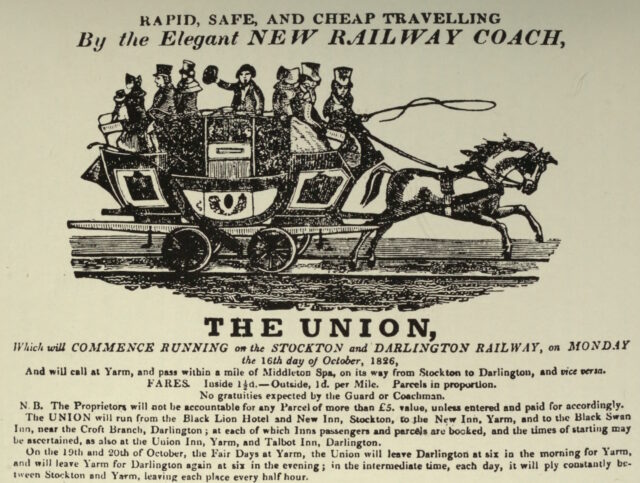

Over the course of the 1820s, the world’s first inter-city railway line – the Liverpool & Manchester Railway – was constructed. It wasn’t initially anticipated that the new railway would use steam locomotives at all: the technology was in its infancy, and the experience of the Stockton & Darlington railway, over on the other side of the Pennines, shows why.

The Stockton & Darlington railway was opened five years before the new Liverpool & Manchester Railway, and pulled its trains using a mixture of steam locomotives and horses1. The early steam locomotives they used turned out to be pretty disastrous. Early ones frequently broke their cast-iron wheels so frequently; some were too heavy for the lines and needed reconstruction to spread their weight; others had their boilers explode (probably after safety valves failed to relieve the steam pressure that builds up after bringing the vehicle to a halt); all got tied-up in arguments about their cost-efficiency relative to horses.

Nearby, at Hetton colliery – the first railway ever to be designed to never require animal power – the Hetton Coal Company had become so-dissatisfied with the reliability and performance of their steam locomotives – especially on the inclines – that they’d had the entire motive system. They’d installed a cable railway – a static steam engine pulled the mine carts up the hill, rather than locomotives.

This kind of thing was happening all over the place, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company were understandably cautious about hitching their wagon to the promise of steam locomotives on their new railway. Furthermore, they were concerned about the negative publicity associated with introducing to populated areas these unpopular smoke-belching engines.

But they were willing to be proven wrong, especially after George Stephenson pointed out that this new, long, railway could find itself completely crippled by a single breakdown were it to adopt a cable system. So: they organised a competition, the Rainhill Trials, to allow locomotive engineers the chance to prove their engines were up to the challenge.

The challenge was this: from a cold start, each locomotive had to haul three times its own weight (including their supply of fuel and water), a mile and three-quarters (the first and last eighth of a mile of which were for acceleration and deceleration, but the rest of which must maintain a speed of at least 10mph), ten times, then stop for a break before doing it all again.

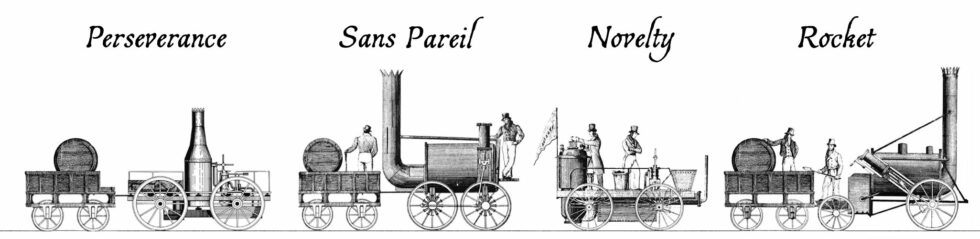

Four steam locomotives took part in the competition that week. Perseverance was damaged in-transit on the way to the competition and was only able to take part on the last day (and then only achieving a top speed of 6mph), but apparently its use of roller bearing axles was pioneering. The very traditionally-designed Sans Pareil was over the competition’s weight limit, burned-inefficiently (thanks perhaps to an overenthusiastic blastpipe that vented unburned coke right out of the funnel!), and broke down when one of its cylinders cracked2. Lightweight Novelty – built in a hurry probably out of a fire engine’s parts – was a crowd favourite with its integrated tender and high top speed, but kept breaking down in ways that could not be repaired on-site. And finally, of course, there was Rocket, which showcased a combination of clever innovations already used in steam engines and locomotives elsewhere to wow the judges and take home the prize.

But there was a fifth competitor in the Rainhill Trials, and it was very different from the other four.

Cycloped

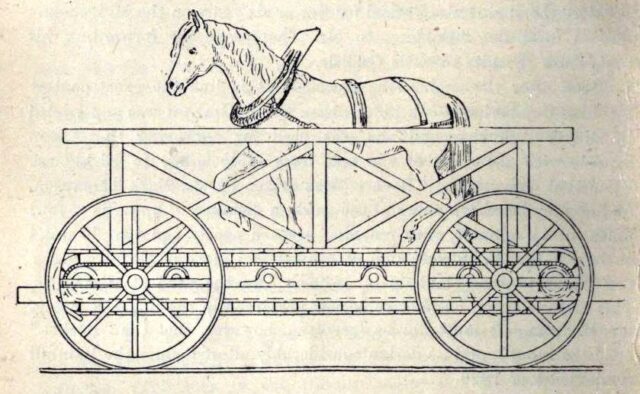

When you hear the words horse-powered locomotive, you probably think of a horse-drawn train. But that’s not a locomotive: a locomotive is a vehicle that, by definition, propels itself3. Which means that a horse-powered locomotive needs to carry the horse that provides its power…

…which is exactly what Cycloped did. A horse runs on a treadmill, which turns the wheels of a vehicle. The vehicle (with the horse on it) move. Tada!4

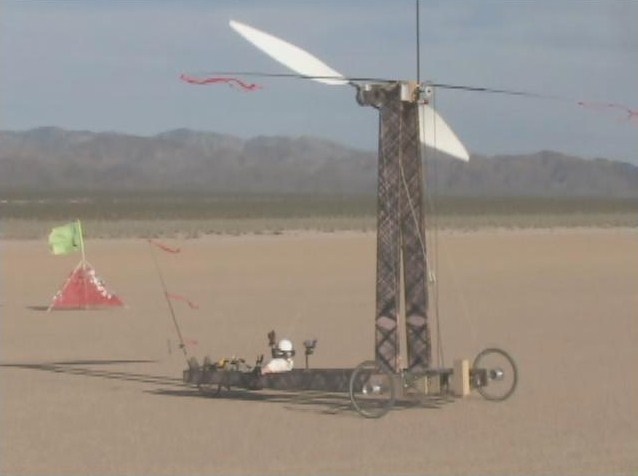

You might look at that design and, not-unreasonably, decide that it must be less-efficient than just having the horse pull the damn vehicle in the first place. But that isn’t necessarily the case. Consider the bicycle which can transport itself and a human both faster and using less-energy than the human would achieve by walking. Or look at wind turbine powered vehicles like Blackbird, which was capable of driving under wind power alone at three times the speed of a tailwind and twice the speed of a headwind. It is mechanically-possible to improve the speed and efficiency of a machine despite adding mass, so long as your force multipliers (e.g. gearing) is done right.

Cycloped didn’t work very well. It was slower than the steam locomotives and at some point the horse fell through the floor of the treadmill. But as I’ve argued above, the principle was sound, and – in this early era of the steam locomotive, with all their faults – a handful of other horse-powered locomotives would be built over the coming decades.

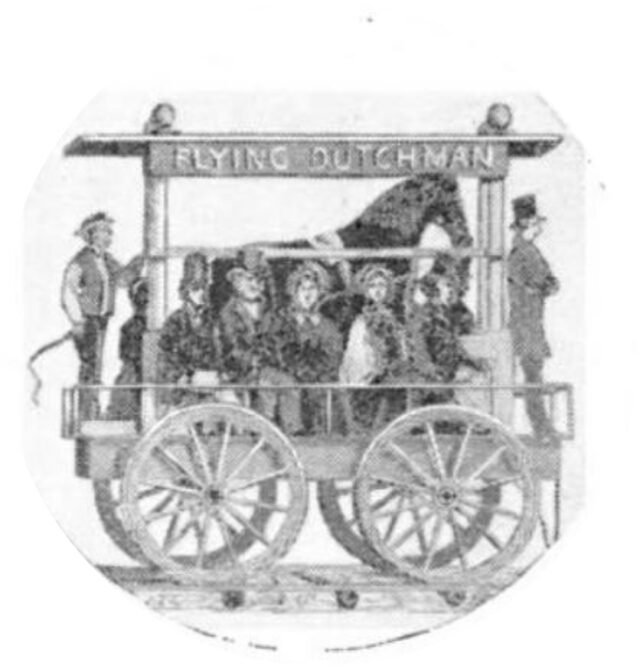

Over in the USA, the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company successfully operated a passenger service using the Flying Dutchman, a horse-powered locomotive with twelve seats for passengers. Capable of travelling at 12mph, this demonstrated efficiency multiplication over having the same horse pull the vehicle (which would either require fewer passengers or a dramatically reduced speed).

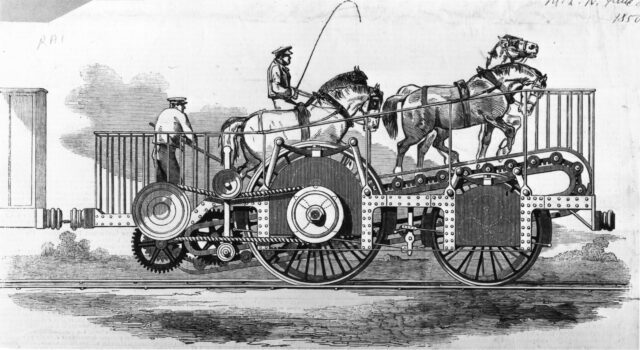

As late as the early 1850s, people were still considering this strange approach. The 1851 Great Exhibition at the then brand-new Crystal Palace featured Impulsoria, which represents probably the pinnacle of this particular technological dead-end.

Capable of speeds up to 20mph, it could go toe-to-toe with many contemporary steam locomotives, and it featured a gearbox to allow the speed and even direction of travel to be controlled by the driver without having to adjust the walking speed of the two to four horses that provided the motive force.

Personally, I’d love to have a go on something like the Flying Dutchman: riding a horse-powered vehicle with the horse is just such a crazy idea, and a road-capable variant could make for a much better city tour vehicle than those 10-person bike things, especially if you’re touring a city with a particularly equestrian history.

Footnotes

1 From 1828 the Stockton & Darlington railway used horse power only to pull their empty coal trucks back uphill to the mines, letting gravity do the work of bringing the full carts back down again. But how to get the horses back down again? The solution was the dandy wagon, a special carriage that a horse rides in at the back of a train of coal trucks. It’s worth looking at a picture of one, they’re brilliant!

2 Sans Pareil’s cylinder breakdown was a bit of a spicy issue at the time because its cylinders had been manufactured at the workshop of their rival George Stephenson, and turned out to have defects.

3 You can argue in the comments whether a horse itself is a kind of locomotive. Also – and this is the really important question – whether or not Fred Flintstone’s car, which is propelled by his feed, is a kind locomotive or not.

4 Entering Cycloped into a locomotive competition that expected, but didn’t explicitly state, that entrants had to be a steam-powered locomotive, sounds like exactly the kind of creative circumventing of the rules that we all loved Babe (1995) for. Somebody should make a film about Cycloped.

“Over the course of the 1920s” – I think you mean the 1820s…

The only problem with the Flying Dutchman, as with the internal combustion engine, would be dealing with the exhaust.

Thanks! Corrected!