Well, it’s now Christmas here in Britain, anyway!

Merry Christmas, MegaLoungeUK

This self-post was originally posted to /r/MegaLoungeUK. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

Dan Q

This self-post was originally posted to /r/MegaLoungeUK. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

Well, it’s now Christmas here in Britain, anyway!

This link was originally posted to /r/todayilearned. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: http://mentalfloss.com/article/12434/foot-powder-ran-mayor-and-won

Picoaza is a relatively small village near Ecuador’s Pacific coast. It’s the site of an archaeological treasure: a settlement dating back before the time of Christopher Columbus. It’s also a rather poor area, where clean drinking water, sewer systems, and telephone service are inadequate at best.

It is also the only town in the known world to elect, as its mayor, a brand of foot powder.

During Picoaza’s 1967 mayoral campaign, a foot powder company ran politically themed ads promoting their product, Pulvapies. Leading up to election day, their message, translated, was non-partisan and straightforward: “Vote for any candidate, but if you want well-being and hygiene, vote for Pulvapies.” They distributed leaflets that were more to the point: ”For Mayor: Honorable Pulvapies.”

The campaign worked — in one sense, at least. While we don’t know if sales of Pulvapies increased, we do know that write-in ballots voting for the product did. Pulvapies received enough write-in votes to win the election. What happened afterward is unknown in the English-speaking world — as Snopes notes, no English-language media outlets followed up on how Picoaza resolved the obvious problem of having foot deodorant as the executive-in-chief.

This link was originally posted to /r/MegaLoungeBrazil. See

more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ce/Brazilwood_tree_in_Vit%C3%B3ria%2C_ES%2C_Brazil.jpg

When Portugese explorers landed in the area of South America we now call Brazil in the year 1500, they discovered the caesalpinia echinata tree growing there. They noticed that this tree had a similar red-coloured wood as the related Sappanwood (caesalpinia sappan) tree, native to Asia, and that a similarly-useful red dye could be extracted from this wood, so they gave the newly-discovered species the same name that they used to describe its Asian relative: pau-brasil. Pau means ‘wood’ and brasil probably derives from brasa, the Portugese word for “ember”, so pau-brasil best translates as “emberwood”. The colour of its wood was clearly known to the natives, too, who called it ibirapitanga – Tupi for, literally, “red wood”.

At this time, the Portugese called the area Ilha de Vera Cruz (“Island of the True Cross”), after the holy day on which the Portugese captain Pedro Álvares Cabral landed there. On his return trip, he discovered that Brazil was not an island but connected to a much larger continent, and renamed it Terra de Santa Cruz (“Land of the Holy Cross”). Another common name in the years that followed was come up with by Italian merchants who met with members of Cabral’s crew – Terra di Papaga (“Land of Parrots”) – which I personally think would have been an awesome name for the country.

Anyway: a group of merchants moved over to the new Portugese colony in the first decade of the 16th century in order to harvest the wood of the caesalpinia echinata trees. You see, it turned out to be even better as a source of red dye than the previously commercially-exploited caesalpinia sappan. Prior to this time, this particular kind of red dye was very popular in Europe, and could only be imported via India (which was very expensive). By being able to produce an even higher-quality dye at lower cost made the colonial Portugese merchants very rich.

The Portugese had a habit at the time of coming to name their colonies after the commercial product they exploited there: see, for example, the Ilha da Madeira, or “Maderia Island”, which literally translates as “Island of Wood”. This habit continued in their new colony too: the São Francisco River (the longest river whose entire length is in Brazil and the fourth-longest in South America) was labelled on a 1502 map as Rio D Brasil (“River of Brasil”), which was clearly a reference to the great quantity of pau-brasil trees that could be found there. By 1509, the general term for the land had become terra do Brasil daleem do mar Ociano (“land of Brazil beyond the Ocean sea”), and in 1516 the name received official recognition with the appointment by the Portugese king of the first “governor of Brasil”.

A clue to this history appears today in the name of inhabitants of Brazil, who call themselves Brasileiro: the -eiro suffix means ‘worker’, similar to putting -er on the end of an English word to get e.g. baker or hunter – clearly this refers to the use of the Tupi tribes by the Portugese as woodcutters during their colonial era (the usual Portugese suffix for ‘person who lives in’ is not -eiro but -ano).

So there you have it: the nation of Brazil is almost certainly named after a type of tree, and is the only nation in the world for which this is the case. Hope you enjoyed your history lesson, and that you continue to enjoy your stay in /r/MegaLoungeBrazil!

tl;dr: 16th century Portugese colonists and subsequent merchants named Brazil after pau-brazil, the name they gave to a type of tree that grew there, which was in turn named after a related Asian tree of the same name. When this new tree became economically valuable, they began referring to the whole area by that name, as was Portugese tradition at the time.

This self-post was originally posted to /r/MegaLoungeSol. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

We were chatting about the MegaLounges etc.; he seemed agitated that I have multiple Reddit accounts (and one of my ‘other’ ones had recently found its way into the MegaLounge after a comment I’d made, using it). I ended up enumerating my accounts, to him (I’ve made a couple of throwaways over the years, and I maintain a couple of novelty accounts and a couple of alternate identities to talk about things that I don’t want associated with this one), and he was shocked that I had so many (it’s really not that many!).

Then later, we wrapped Christmas presents together. And my partner’s baby was there, except she could talk.

I shouldn’t have drunk as much as I did, last night.

This checkin to GLG9J392 Team Mee Productions Cache #1 reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

FTF on my way home from work this evening. The darkness didn’t make it any harder to find, once I’d worked out where I was looking. SL, TFTC.

This self-post was originally posted to /r/MegaLoungeFrance. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

A Royale Lounge with Cheese.

Here! Have some cheese. Cheese! CHEESE! CHEESE FOR EVERYBODY!!!

I might not be getting enough sleep.

The most recent column in Savage Love had a theme featuring letters on the subject of gender-neutrality and genderfluidity. You’ve probably come across the term “genderqueer” conceptually even if you’re not aware of people within your own life to whom the title might be applied: people who might consider themselves to be of no gender, or of multiple genders, or of variable gender, of a non-binary gender, or trans (gender’s a complex subject, yo!).

For about the last four or five years, I’ve been able to gradually managed to change my honorific title (where one is required) in many places from the traditional and assumed “Mr.” to the gender-neutral “Mx.” Initially, it was only possible to do this where the option was provided to enter a title of one’s choosing – you know: where there’s tickboxes and an “Other:” option – but increasingly, I’ve seen it presented as one of the default options, alongside Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr., and the like. As a title, Mx. is gaining traction.

I’m not genderqueer, mind. I’m cisgender and male: a well-understood and popular gender that’s even got a convenient and widely-used word for it: “man”. My use of “Mx.” in a variety of places is based not upon what I consider my gender to be but upon the fact that my gender shouldn’t matter. HMRC, pictured above, is a great example: they only communicate with me by post and by email (so there’s no identification advantage in implying a gender as which I’m likely to be presenting), and what gender I am damn well shouldn’t have any impact on how much tax I pay or how I pay it anyway: it’s redundant information! So why demand I provide a title at all?

I don’t object to being “Mr.”, of course. Just the other day, while placing an order for some Christmas supplies, a butcher in Oxford’s covered market referred to me as “Mr. Q”. Which is absolutely fine, because that’s the title (and gender) by which he’ll identify me when I turn up the week after next to pick up some meat.

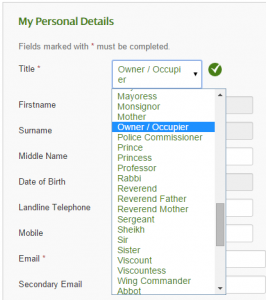

I’d prefer not to use an honorific title at all: I fail to see what it adds to my name or my identity to put “Mr.” in it! But where it’s (a) for some-reason required (often because programmers have a blind spot for things like names and titles), and (b) my gender shouldn’t matter, don’t be surprised if I put “Mx.” in your form.

And if after all of that you don’t offer me that option, know that I’m going to pick something stupid just to mess with your data. That’s Wing Commander Dan Q’s promise.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I like the irregular verbs of English, all 180 of them, because of what they tell us about the history of the language and the human minds that have perpetuated it.

The irregulars are defiantly quirky. Thousands of verbs monotonously take the -ed suffix for their past tense forms, but ring mutates to rang, not ringed, catch becomes caught, hit doesn’t do anything, and go is replaced by an entirely different word, went (a usurping of the old past tense of to wend, which itself once followed the pattern we see in send-sent and bend-bent). No wonder irregular verbs are banned in “rationally designed” languages like Esperanto and Orwell’s Newspeak — and why recently a woman in search of a nonconformist soul-mate wrote a personal ad that began, “Are you an irregular verb?”

Since irregulars are unpredictable, people can’t derive them on the fly as they talk, but have to have memorized them beforehand one by one, just like simple unconjugated words, which are also unpredictable. (The word duck does not look like a duck, walk like a duck, or quack like a duck.) Indeed, the irregulars are all good, basic, English words: Anglo-Saxon monosyllables. (The seeming exceptions are just monosyllables disguised by a prefix: became is be- + came; understood is under- + stood; forgot is for- + got).

There are tantalizing patterns among the irregulars: ring-rang, sing-sang, spring-sprang, drink-drank, shrink-shrank, sink-sank, stink-stank; blow-blew grow-grew, know-knew, throw-threw, draw-drew, fly-flew, slay-slew; swear-swore, wear-wore, bear-bore, tear-tore. But they still resist being captured by a rule. Next to sing-sang we find not cling-clang but cling-clung, not think-thank but think-thought, not blink-blank but blink-blinked. In between blow-blew and grow-grew sits glow-glowed. Wear-wore may inspire swear-swore, but tear-tore does not inspire stare-store. This chaos is a legacy of the Indo-Europeans, the remarkable prehistoric tribe whose language took over most of Europe and southwestern Asia. Their language formed tenses using rules that regularly replaced one vowel with another. But as pronunciation habits changed in their descendant tribes, the rules became opaque to children and eventually died; the irregular past tense forms are their fossils. So every time we use an irregular verb, we are continuing a game of Broken Telephone that has gone on for more than five thousand years.

I especially like the way that irregular verbs graciously relinquish their past tense forms in special circumstances, giving rise to a set of quirks that have puzzled language mavens for decades but which follow an elegant principle that every speaker of the language — every jock, every 4-year-old — tacitly knows. In baseball, one says that a slugger has flied out; no mere mortal has ever “flown out” to center field. When the designated goon on a hockey team is sent to the penalty box for nearly decapitating the opposing team’s finesse player, he has high-sticked, not high-stuck. Ross Perot has grandstanded, but he has never grandstood, and the Serbs have ringed Sarajevo with artillery, but have never rung it. What these suddenly-regular verbs have in common is that they are based on nouns: to hit a fly that gets caught, to clobber with a high stick, to play to the grandstand, to form a ring around. These are verbs with noun roots, and a noun cannot have an irregular past tense connected to it because a noun cannot have a past tense at all — what would it mean for a hockey stick to have a past tense? So the irregular form is sealed off and the regular “add -ed” rule fills the vacuum. One of the wonderful features about this law is that it belies the accusations of self-appointed guardians of the language that modern speakers are slowly eroding the noun-verb distinction by cavalierly turning nouns into verbs (to parent, to input, to impact, and so on). Verbing nouns makes the language more sophisticated, not less so: people use different kinds of past tense forms for plain old verbs and verbs based on nouns, so they must be keeping track of the difference between the two.

Do irregular verbs have a future? At first glance, the prospects do not seem good. Old English had more than twice as many irregular verbs as we do today. As some of the verbs became less common, like cleave-clove, abide-abode, and geld-gelt, children failed to memorize their irregular forms and applied the -ed rule instead (just as today children are apt to say winded and speaked). The irregular forms were doomed for these children’s children and for all subsequent generations (though some of the dead irregulars have left souvenirs among the English adjectives, like cloven, cleft, shod, gilt, and pent).

Not only is the irregular class losing members by emigration, it is not gaining new ones by immigration. When new verbs enter English via onomatopoeia (to ding, to ping), borrowings from other languages (deride and succumb from Latin), and conversions from nouns (fly out), the regular rule has first dibs on them. The language ends up with dinged, pinged, derided, succumbed, and flied out, not dang, pang, derode, succame, or flew out.

But many of the irregulars can sleep securely, for they have two things on their side. One is their sheer frequency in the language. The ten commonest verbs in English (be, have, do, say, make, go, take, come, see, and get) are all irregular, and about 70% of the time we use a verb, it is an irregular verb. And children have a wondrous capacity for memorizing words; they pick up a new one every two hours, accumulating 60,000 by high school. Eighty irregulars are common enough that children use them before they learn to read, and I predict they will stay in the language indefinitely.

And there is one small opportunity for growth. Irregulars have to be memorized, but human memory distills out any pattern it can find in the memorized items. People occasionally apply a pattern to a new verb in an attempt to be cool, funny, or distinctive. Dizzy Dean slood into second base; a Boston eatery once sold T-shirts that read “I got schrod at Legal Seafood,” and many people occasionally report that they snoze, squoze, shat, or have tooken something. Could such forms ever catch on and become standard? Perhaps. A century ago, some creative speaker must have been impressed by the pattern in stick-stuck and strike-struck, and that is how our youngest irregular, snuck, sneaked in.

Steven Pinker is Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, and the author of The Language Instinct (William Morrow & Co., New York, 1994).

This content was originally shared via Google Currents, at https://currents.google.com/103645469476905576119/posts/LPssmFuqjXj. It was added to this site retroactively, on 2 February 2022.

One of the great joys of owning a house is that you can do pretty much whatever you please with it. I celebrated Ruth, JTA and I’s purchase of Greendale last year by wall-mounting not one but two televisions and putting shelves up everywhere. But honestly, a little bit of DIY isn’t that unusual nor special. We’ve got plans for a few other changes to the house, but right now we’re pushing our eco-credentials: we had cavity wall insulation added to the older parts of the building the other week and an electric car charging port added not long before that. And then… came this week’s big change.

Solar photovoltaics! They’re cool, they’re (becoming) economical, and we’ve got this big roof that faces almost due-South that would otherwise be just sitting there catching rain. Why not show off our green credentials and save ourselves some money by covering it with solar cells, we thought.

Because it’s me, I ended up speaking to five different companies and, after removing one from the running for employing a snake for a salesman, collecting seven quotes from the remaining four, I began to do my own research. The sheer variety of panels, inverters, layouts and configurations (all of which are described in their technical sheets using terms that in turn required a little research into electrical efficiency and dusting off formulas I’d barely used since my physics GCSE exam) are mind-boggling. Monolithic, string, or micro-inverters? 250w or 327w panels? Where to run the cables that connect the inverter (in the attic) to the generation meter and fusebox (in the ground floor toilet)? Needless to say, every company had a different idea about the “best way” to do it – sometimes subtly different, sometimes dramatically – and had a clear agenda to push. So – as somebody not suckered in to a quick deal – I went and did the background reading first.

In case you’re not yet aware, let me tell you the three reasons that solar panels are a great idea, economically-speaking. Firstly, of course, they make electricity out of sunlight which you can then use: that’s pretty cool. With good discipline and a monitoring tool either in hardware or software, you can discover the times that you’re making more power than you’re using, and use that moment to run the dishwasher or washing machine or car charger or whatever. Or the tumble drier, I suppose, although if you’re using the tumble drier because it’s sunny then you lose a couple of your ‘green points’ right there. So yeah: free energy is a nice selling point.

The second point is that the grid will buy the energy you make but don’t use. That’s pretty cool, too – if it’s a sunny day but there’s nobody in the house, then our electricity meter will run backwards: we’re selling power back to the grid for consumption by our neighbours. Your energy provider pays you for that, although they only pay you about a third of what you pay them to get the energy back again if you need it later, so it’s always more-efficient to use the power (if you’ve genuinely got something to use it for, like ad-hoc bitcoin mining or something) than to sell it. That said, it’s still “free money”, so you needn’t complain too much.

The third way that solar panels make economic sense is still one of the most-exciting, though. In order to enhance uptake of solar power and thus improve the chance that we hit the carbon emission reduction targets that Britain committed to at the Kyoto Protocol (and thus avoid a multi-billion-pound fine), the government subsidises renewable microgeneration plants. If you install solar panels on your house before the end of this year (when the subsidy is set to decrease) the government will pay you 14.38p per unit of electricity you produce… whether you use it or whether you sell it. That rate is retail price index linked and guaranteed for 20 years, and as a result residential solar installations invariably “pay for themselves” within that period, making them a logical investment for anybody who’s got a suitable roof and who otherwise has the money just sitting around. (If you don’t have the cash to hand, it might be worth taking out a loan to pay for solar panels, but then the maths gets a lot more complicated.)

The scaffolding went up on the afternoon of day one, and I took the opportunity to climb up myself and give the gutters a good cleaning-out, because it’s a lot easier to do that from a fixed platform than it is from our wobbly “community ladder”. On day two, a team of electricians and a solar expert appeared at breakfast time and by 3pm they were gone, leaving behind a fully-functional solar array. On day three, we were promised that the scaffolding company would reappear and remove the climbing frame from our garden, but it’s now dark and they’ve not been seen yet, which isn’t ideal but isn’t the end of the world either: not least because Ruth’s been unwell and thus hasn’t had the chance to get up and see the view from the top of it, yet.

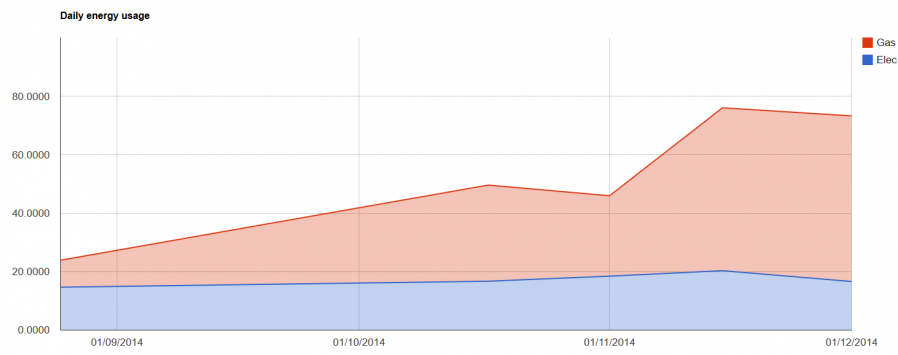

We made about 4 units of electricity on our first day, which didn’t seem bad for an overcast afternoon about a fortnight away from the shortest day of the year. That’s about enough to power every light bulb in the house for the duration that the sun was in the sky, plus a little extra (we didn’t opt to commemorate the occasion by leaving the fridge door open in order to ensure that we used every scrap of the power we generated).

Because I’m a bit of a data nerd these years, I’ve been monitoring our energy usage lately anyway and as a result I’ve got an interesting baseline against which to compare the effectiveness of this new addition. And because there’s no point in being a data nerd if you don’t get to share the data love, I will of course be telling you all about it as soon as I know more.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This checkin to GC5H8YX Boundary Brook: The Mouth of the Brook reflects a geocaching.com log entry. See more of Dan's cache logs.

So pleased to see that this – an extension to my favourite series within the Oxford ring road – exists. Looking forward to an expedition to it as soon as I can manage it. I suspect that my friend lizrosemccarthy might beat me there though: she might even get FTF, as this cache is almost on her doorstep!