I have this exact same ride-on mower, but mine doesn’t do this. I feel cheated.

Mow-Rio Kart

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I have this exact same ride-on mower, but mine doesn’t do this. I feel cheated.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I don’t normally watch videos of other people playing video games. I’m even less inclined to watch “walkthroughs”.

This, though, isn’t a walkthrough. It’s basically the opposite of a walkthrough: this is somebody (slowly, painstakingly) playing through Skyrim: Special Edition without using any of the movement controls (WASD/left stick) whatsoever. Wait, what? How is such a thing possible?

That’s what makes the video so compelling. The creator used so many bizarre quirks and exploits to even make this crazy stupid idea work at all. Like (among many, many more):

This video’s just beautiful: the cumulation of what must be hundreds or thousands of person-hours of probing the “edges” of Skyrim‘s engine to discover all of the potentially exploitable bugs that make it possible.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I quite enjoyed this progressive game: it’s a little bit different than most, the theming is fun, it lends itself to multiple strategies, and it’s not geared towards making you wait for longer and longer intervals (as is common in this genre): there’s always something you can be doing to get closer to your goal.

You’ll need a mouse with left and right buttons.

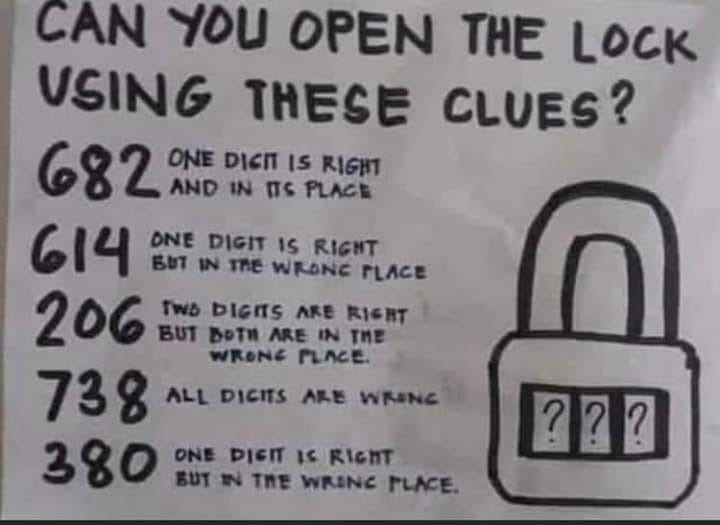

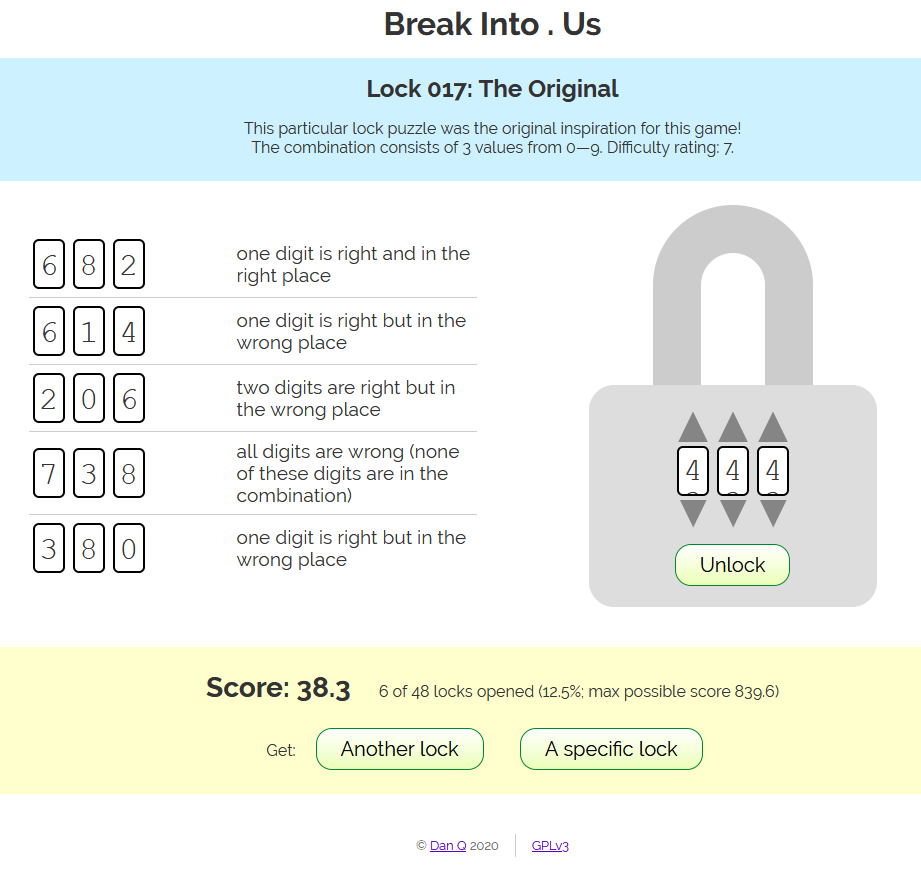

I’ve made a puzzle game about breaking open padlocks. If you just want to play the game, go play the game. Or read on for the how-and-why of its creation.

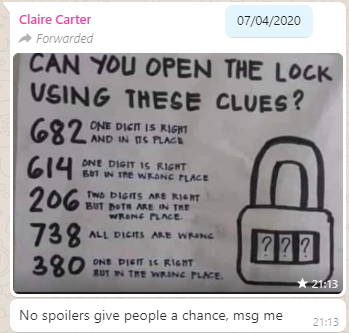

About three months ago, my friend Claire, in a WhatsApp group we both frequent, shared a brainteaser:

The puzzle was to be interpreted as follows: you have a three-digit combination lock with numbers 0-9; so 1,000 possible combinations in total. Bulls and Cows-style, a series of clues indicate how “close” each of several pre-established “guesses” are. In “bulls and cows” nomenclature, a “bull” is a correctly-guessed digit in the correct location and a “cow” is a correctly-guessed digit in the wrong location, so the puzzle’s clues are:

By the time I’d solved her puzzle the conventional way I was already interested in the possibility of implementing a general-case computerised solver for this kind of puzzle, so I did. My solver uses a simple “brute force” technique, as follows:

Visualising the solver as a series of bisections of a search space got me thinking about something else: wouldn’t this be a perfectly reasonable way to programatically generate puzzles of this type, too? Something like this:

Interestingly, this approach is almost the opposite of what a human would probably do. A human, tasked with creating a puzzle of this sort, would probably choose the answer first and then come up with clues that describe it. Instead, though, my solution would come up with clues, apply them, and then see what’s left-over at the end.

I expanded my generator to go beyond simple bulls-or-cows clues: it’s also capable of generating clues that make reference to the balance of odd and even digits (in a numeric lock), the number of different digits used in the combination, the sum of the digits of the combination, and whether or not the correct combination “ascends” or “descends”. I’ve ideas for other possible clue types too, which could be valuable to make even tougher combination locks: e.g. specifying how many numbers in the combination are adjacent to a consecutive number, specifying the types of number that the sum of the digits adds to (e.g. “the sum of the digits is a prime number”) and so on.

Next up, I wanted to make a based interface so that people could have a go at the puzzles in their web browser, track their progress through the levels, get a “score” based on the number and difficulty of the locks that they’d cracked (so they can compare it to their friends), and save their progress to carry on next time.

I implemented in pure vanilla HTML, CSS, SVG and JS, with no dependencies. Compressed, it delivers to your browser and is ready-to-play in a little under 10kB, most of which is the puzzles themselves (which are pregenerated and stored in a JSON file). Naturally, it lends itself well to running offline, so it’s PWA-enhanced with a service worker so it can be “installed” onto your device, too, and it’ll check for bonus puzzles and other updates periodically.

Honestly, the hardest bit of implementing the frontend was the “spinnable” digits: depending on your browser, these are an endless-scrolling <ul> implemented mostly in CSS and with snap points set, and then some JS to work out “what you meant” based on where you span to. Which feels like the right way to implement such a thing, but was a lot more work than putting together my own control, not least because of browser inconsistencies in the implementation of snap points.

Anyway: you should go and play the game, now, and let me know what you think. Is it worth expanding and improving? Should I leave it as it is? I’m open to ideas (and if you don’t like that I’m not implementing your suggestions, you can always fork a copy of the code and change it yourself)!

Or if you’d like to see some of the other JavaScript experiments I’ve done, you might enjoy my “cheating” hangman game, my recreation of the lunar lander game I wrote in college, or rediscover that time I was ill and came up the worst conceivable tool to calculate Pi.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I managed to crack this on my second attempt, but then: I did play an ungodly amount of Kerbal Space Program a few years back. I guess this means I’m now qualified to be an astronaut, right? I’d better update my CV…

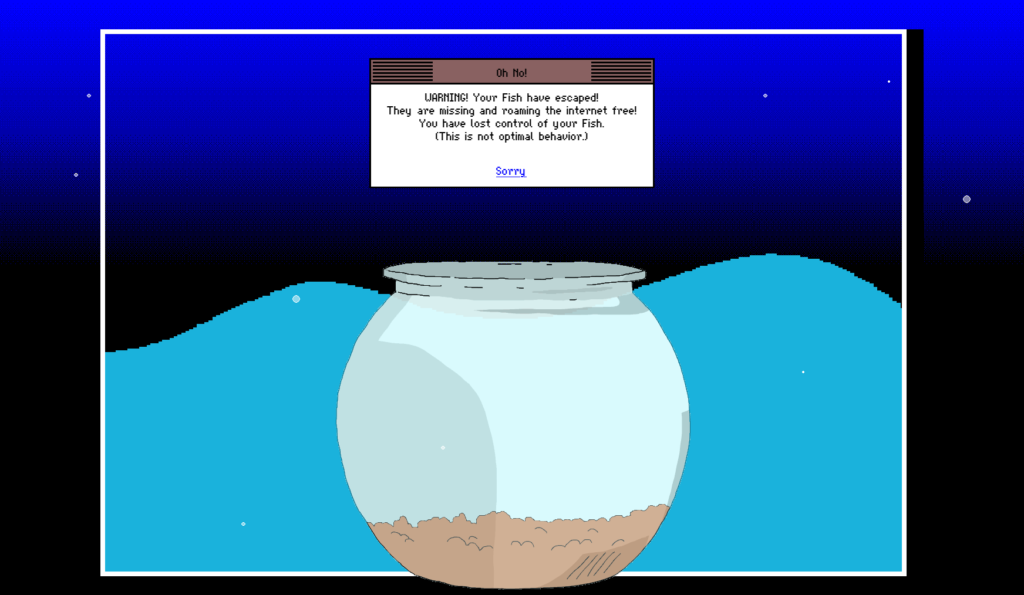

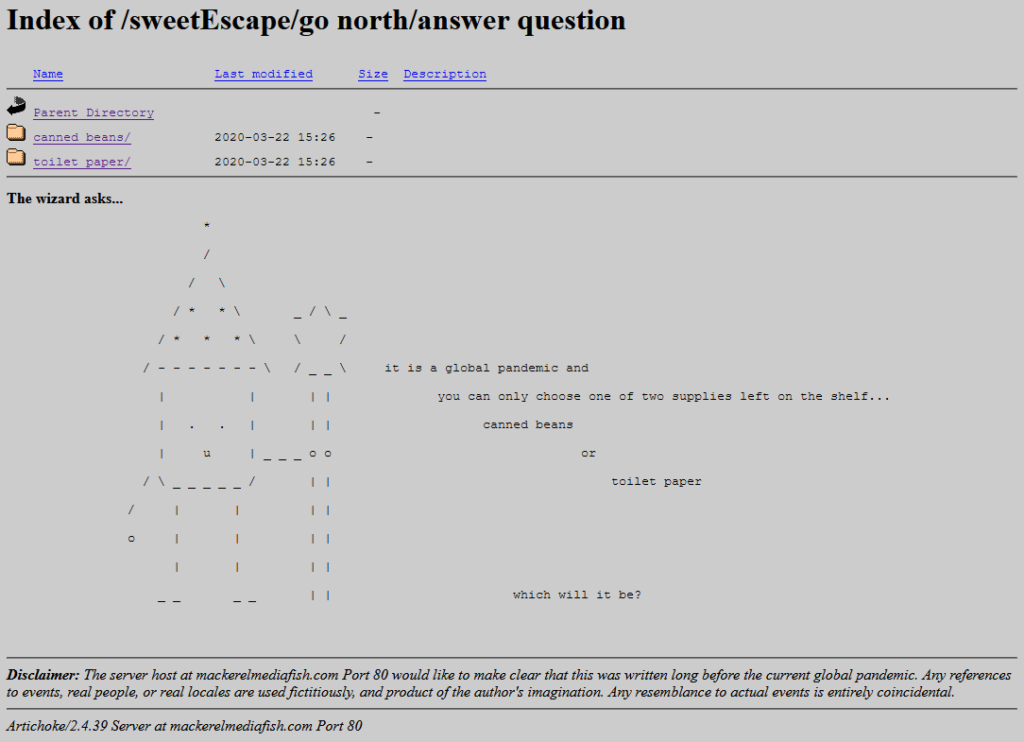

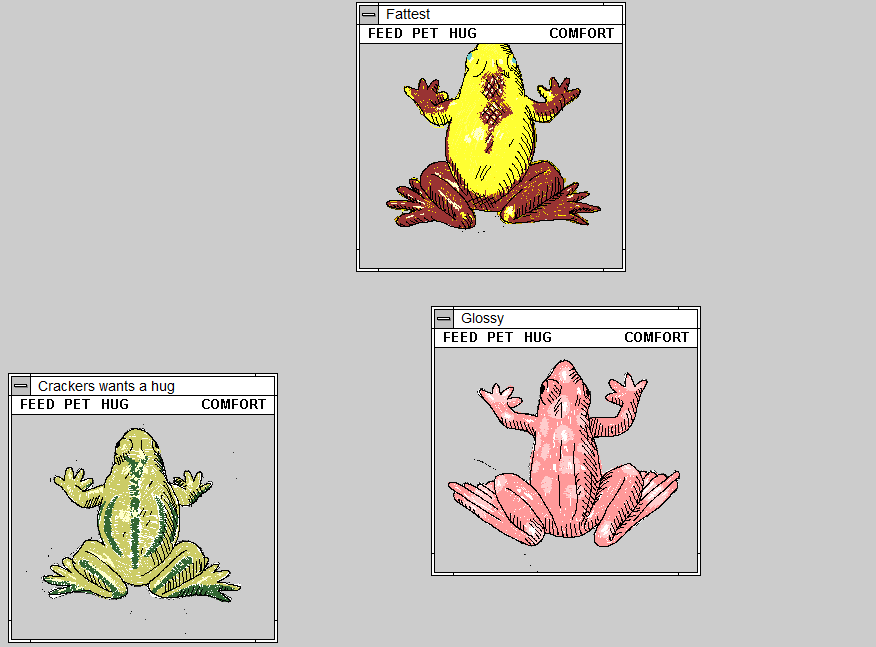

Normally this kind of thing would go into the ballooning dump of “things I’ve enjoyed on the Internet” that is my reposts archive. But sometimes something is so perfect that you have to try to help it see the widest audience it can, right? And today, that thing is: Mackerelmedia Fish.

What is Mackerelmedia Fish? I’ve had a thorough and pretty complete experience of it, now, and I’m still not sure. It’s one or more (or none) of these, for sure, maybe:

Rock Paper Shotgun’s article about it opens with “I don’t know where to begin with this—literally, figuratively, existentially?” That sounds about right.

What I can tell you with confident is what playing feels like. And what it feels like is the moment when you’ve gotten bored waiting for page 20 of Argon Zark to finish appear so you decide to reread your already-downloaded copy of the 1997 a.r.k bestof book, and for a moment you think to yourself: “Whoah; this must be what living in the future feels like!”

Because back then you didn’t yet have any concept that “living in the future” will involve scavenging for toilet paper while complaining that you can’t stream your favourite shows in 4K on your pocket-sized supercomputer until the weekend.

Mackerelmedia Fish is a mess of half-baked puns, retro graphics, outdated browsing paradigms and broken links. And that’s just part of what makes it great.

It’s also “a short story that’s about the loss of digital history”, its creator Nathalie Lawhead says. If that was her goal, I think she managed it admirably.

If I wasn’t already in love with the game already I would have been when I got to the bit where you navigate through the directory indexes of a series of deepening folders, choose-your-own-adventure style. Nathalie writes, of it:

One thing that I think is also unique about it is using an open directory as a choose your own adventure. The directories are branching. You explore them, and there’s text at the bottom (an htaccess header) that describes the folder you’re in, treating each directory as a landscape. You interact with the files that are in each of these folders, and uncover the story that way.

Back in the naughties I experimented with making choose-your-own-adventure games in exactly this way. I was experimenting with different media by which this kind of branching-choice game could be presented. I envisaged a project in which I’d showcase the same (or a set of related) stories through different approaches. One was “print” (or at least “printable”): came up with a Twee1-to-PDF converter to make “printable” gamebooks. A second was Web hypertext. A third – and this is the one which was most-similar to what Nathalie has now so expertly made real – was FTP! My thinking was that this would be an adventure game that could be played in a browser or even from the command line on any (then-contemporary: FTP clients aren’t so commonplace nowadays) computer. And then, like so many of my projects, the half-made version got put aside “for later” and forgotten about. My solution involved abusing the FTP protocol terribly, but it worked.

(I also looked into ways to make Gopher-powered hypertext fiction and toyed with the idea of using YouTube annotations to make an interactive story web [subsequently done amazingly by Wheezy Waiter, though the death of YouTube annotations in 2017 killed it]. And I’ve still got a prototype I’d like to get back to, someday, of a text-based adventure played entirely through your web browser’s debug console…! But time is not my friend… Maybe I ought to collaborate with somebody else to keep me on-course.)

In any case: Mackerelmedia Fish is fun, weird, nostalgic, inspiring, and surreal, and you should give it a go. You’ll need to be on a Windows or OS X computer to get everything you can out of it, but there’s nothing to stop you starting out on your mobile, I imagine.

Sso long as you’re capable of at least 800 × 600 at 256 colours and have 4MB of RAM, if you know what I mean.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Back in 2011, some folks cross-compiled Doom (the original, not the reboot, obviously) to JavaScript, leveraging the capabilities of the then-relatively-young

<canvas> element and APIs. I was really impressed to see that JavaScript had come so far and that

performance on desktop devices was so slick. Sure, this was an 18-year-old video game, but it was playable in a browser, which was a long way from the environment for which it

was originally developed.

Now Doom 3‘s playable in a browser, and my mind’s blown all over again. This follows almost the same curve – Doom 3’s 16 years old – but it still goes to show that there’s little limit to the power of client-side browser programming. They’ve done this magic with WebAssembly; while WebAssembly goes slightly against my ideas about the open-source nature of the Web, I still respect the power it commands to do heavyweight crunching tasks like this one.

How long until AAA developers start developing with the Web as an additional platform?

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

I know only a small percentage of you use VR and to everyone else I might as well by telling you how spiffy the handrails are up in this ivory tower, but for what it’s worth, Boneworks is the first game in a while to make me think VR might be getting somewhere. It’s not there yet. The physics is full of little niggles as you might expect from a game trying to juggle so much. The major issue with the climbing is only your hands and head can be moved and your in-game legs just flop around getting in the way of things like two stubborn trails of cum dangling off your mum’s chin, but forget all that.

…

Speaking of VR, Yahtzee’s still playing with it and thinks it’s improving, which is high praise. So there’s hope yet.

I really need to dig my heavyweight gear out of the attic, but I’m waiting until we (eventually) move house. And I absolutely agree with Yahtzee’s observation about the value of VR games in which you can sit down, sometimes.

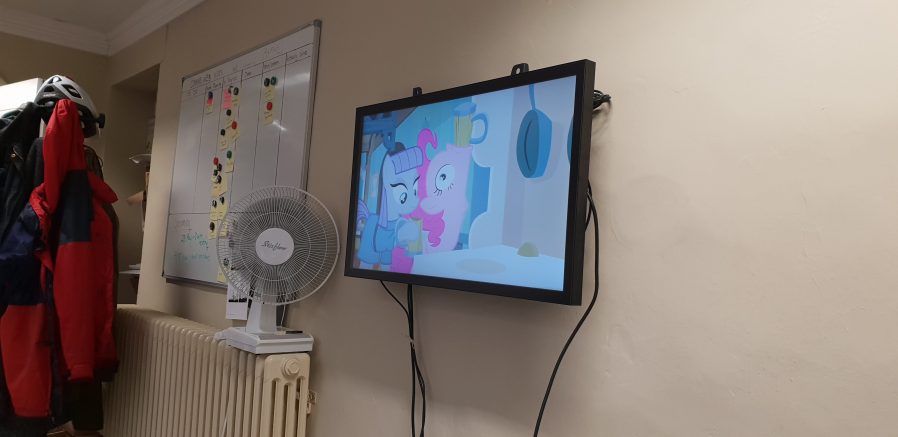

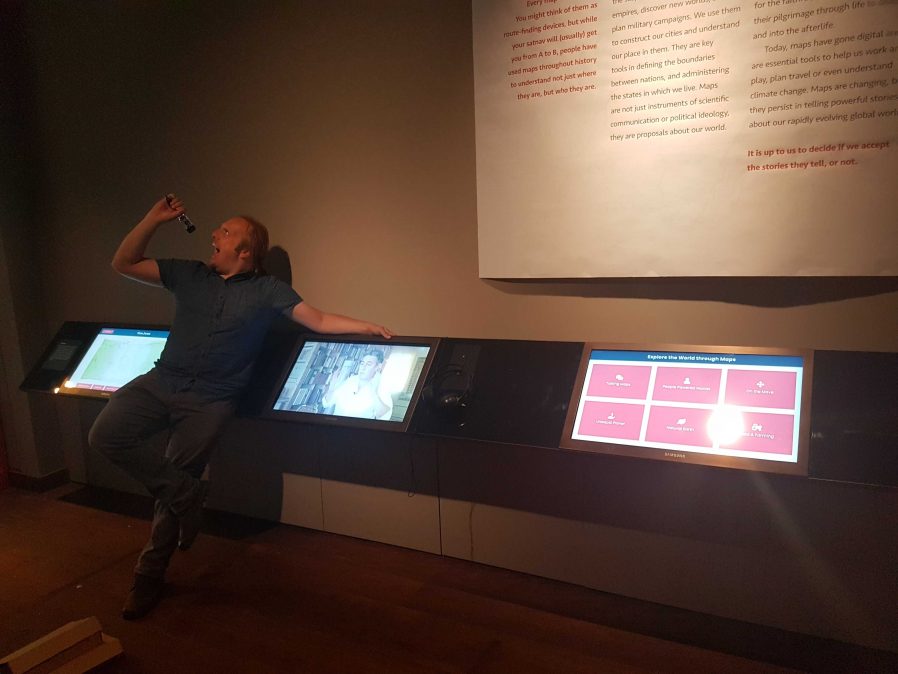

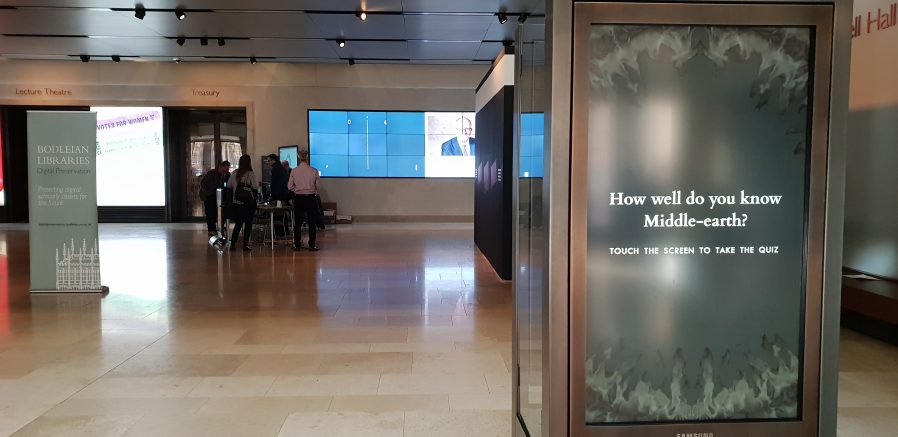

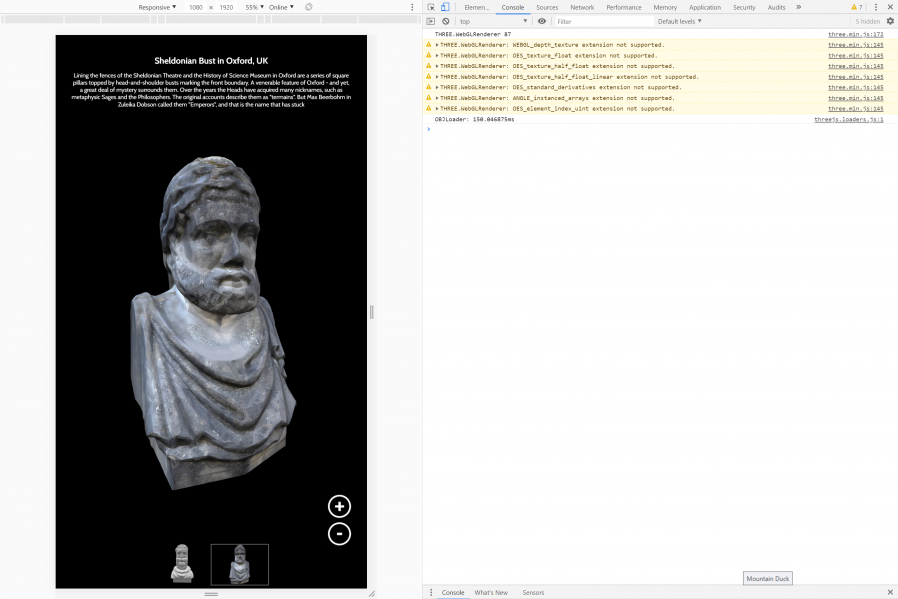

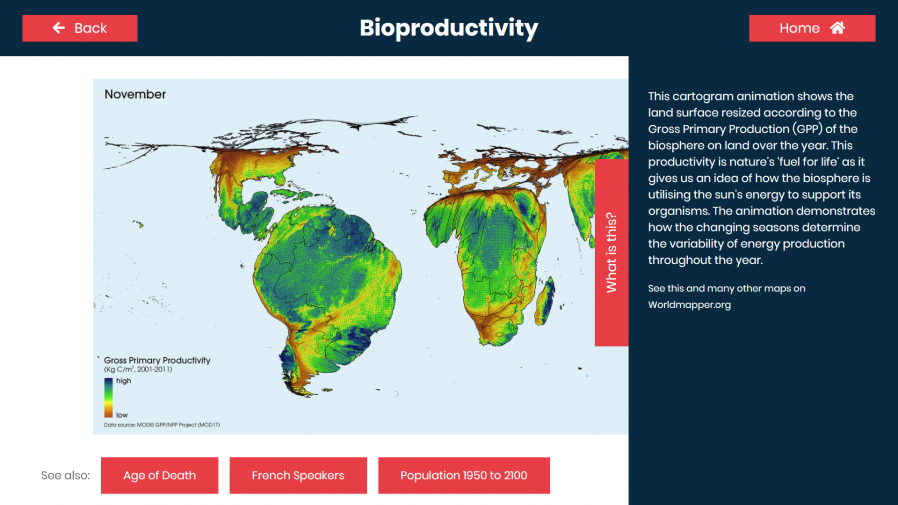

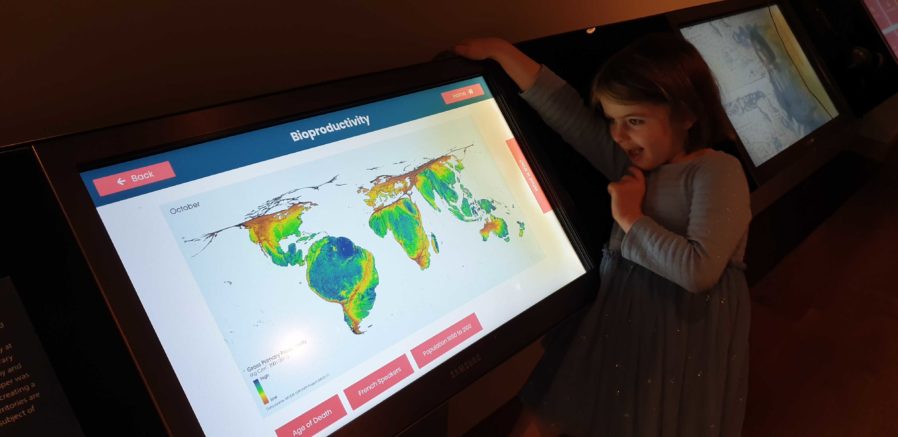

As part of the preparing to leave the Bodleian I’ve been revisiting a lot of the documentation I’ve written over the last eight years. It occurred to me that I’ve never written publicly about how the Bodleian’s digital signage/interactives actually work; there are possible lessons to learn.

The Bodleian‘s digital signage is perhaps more-diverse, both in terms of technology and audience, than that of most organisations. We’ve got signs in areas that are exclusively reader-facing to help students and academics find what they’re looking for, signs in publicly accessible rooms that advertise and educate, and signs in gallery spaces upon which we try to present engaging and often-interactive content to support exhibitions.

Throughout those three spheres, we’ve routinely delivered a diversity of content (let’s just ignore the countdown clock, for now…). Traditional directional signage, advertisements, games, digital exhibitions, interpretation, feedback surveys…

In the vast majority of cases – and this is where the Bodleian’s been unusual (though certainly not unique) among cultural sector institutions – we’ve created those in-house rather than outsourcing them.

To do this economically – the volume of work on interactive signage is inconsistent throughout the year – we needed to align the skills required with skills used elsewhere in the organisation. To do this, we use the web as our medium! Collectively, the Bodleian’s Digital Communications team already had at least some experience in programming, web design, graphic design, research, user testing, copyediting etc.: the essential toolkit for web application development.

By shifting our digital signage platform to lean heavily on web technologies, we were able to leverage talented people we already had to produce things that we might otherwise have had to outsource. This, in turn, meant that more exhibitions and displays get digital enhancement, on a shorter turnaround.

It also means that there’s a tighter integration between exhibition content and content for web and social media: it’s easier for us to re-use content across multiple platforms. Sometimes we’ve even made our digital interactives, or adapted version of them, available directly online, allowing our exhibitions to reach people that can’t get to our physical spaces at all.

On to the technology! We’re using a real mixture of tech: when it’s donated or reclaimed from previous projects (and when the bidding and acquisition processes are, well… as you’d expect at the University of Oxford), you learn not to say no to freebies. Our fleet includes:

When you’re developing content for a very small number of browsers and a limited set of screen sizes, you quickly learn to throw a lot of “best practice” web development out of the window. You’ll never come across a text browser or screen reader, so alt-text doesn’t matter. You’ll never have to rescale responsively, so you might as well absolutely-position almost everything. The devices are all your own, so you never need to ask permission to store cookies. And because you control the platform, you can get away with making configuration tweaks to e.g. allow autoplaying videos with audio. Coming from a conventional web developer background to producing digital signage content makes feels incredibly lazy.

This is the “techy bit”. Skip it?

Using Chrome to run digital signage requires, in the Bodleian’s case, a couple of configuration tweaks and the right command-line switches. We use:

chrome://flags/#overscroll-history-navigation – disabling this prevents users from triggering “back”/”forward” by swiping with two fingers

chrome://flags/#pull-to-refresh – disabling this prevents the user from triggering a “refresh” by scrolling up beyond the top of the page (this only happens on some

kinds of devices)

chrome://flags/#system-keyboard-lock – we don’t use attached keyboards, but if you do, you might want to set this flag so you can use the keyboard.lock()

API to intercept e.g. ALT+F4 so users can’t escape the application

chrome --kiosk --noerrdialogs --allow-file-access-from-files --disable-touch-drag-drop --incognito https://example.com/some/url

Meanwhile, in the application’s CSS code, we set * { user-select: none; } to prevent the user from highlighting

text by selecting it with their finger. We also make heavy use of absolutely-sized/positioned, overflow: hidden blocks to ensure that scrollbars never appear, and

CSS animations to make content feel dynamic and to draw attention to particular elements.

Altogether, this approach gives the Bodleian the capability to produce engaging interactive content at low cost and using the existing skills of their digital and exhibitions teams. It’s not an approach that would work for every cultural institution: in particular, some of the Bodleian’s sister institutions already outsource the technical parts of their web work, and so don’t have the expertise in-house to share with a web-powered digital signage solution.

But for those museums that can fit into this model – or can adapt to do so in future – using the web to produce interactive digital content and digital signage is a highly cost-effective way to engage with visitors, even (or especially!) when dealing with short-lived and/or rotating displays.

It’s also been among my favourite parts of my job at the Bod these last 8½ years, and I’m sure I’ll miss it!

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

But while we’ve learned to distrust user names and text more generally, pictures are different. You can’t synthesize a picture out of nothing, we assume; a picture had to be of someone. Sure a scammer could appropriate someone else’s picture, but doing so is a risky strategy in a world with google reverse search and so forth. So we tend to trust pictures. A business profile with a picture obviously belongs to someone. A match on a dating site may turn out to be 10 pounds heavier or 10 years older than when a picture was taken, but if there’s a picture, the person obviously exists.

No longer. New adverserial machine learning algorithms allow people to rapidly generate synthetic ‘photographs’ of people who have never existed. Already faces of this sort are being used in espionage.

Computers are good, but your visual processing systems are even better. If you know what to look for, you can spot these fakes at a single glance — at least for the time being. The hardware and software used to generate them will continue to improve, and it may be only a few years until humans fall behind in the arms race between forgery and detection.

Our aim is to make you aware of the ease with which digital identities can be faked, and to help you spot these fakes at a single glance.

…

I was at a conference last month where research was presented which concluded pretty solidly that the mechanisms used to make “deepfakes” meant that it was probably impossible to create artificial intelligence that can learn to distinguish between real and fake pictures of humans. Simply put, this is because the way we make such images is with generative adversarial networks, an AI technique which thrives upon having an effective discriminator component, and any research into differentiating between real and fake images feeds the capability of the next generation of discriminators!

Instead, then, the best medium-term defence against deepfakes is training humans to be able to identify them, and that’s what this website aims to do. I was pleased that I did very well on my first attempt (I sort-of knew what to look for already, based on a basic understanding of the underlying technologies) but I was also pleased that I was able to learn to do better with the aid of the authors’ tips. Nice.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Rapping about video games is one thing. Rapping about music/beatmatching video games takes this to a whole new level.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Back in February my friend Katie shared with me an already four-year-old piece of interactive fiction, Bus Station: Unbound, that I’d somehow managed to miss the first time around. In the five months since then I’ve periodically revisited and played through it and finally gotten around to writing a review:

All of the haunting majesty of its subject, and a must-read-thrice plot

Perhaps it helps to be as intimately familiar with Preston Bus Station – in many ways, the subject of the piece – as the protagonist. This work lovingly and faithfully depicts the space and the architecture in a way that’s hauntingly familiar to anybody who knows it personally: right down to the shape of the rubberised tiles near the phone booths, the forbidding shadows of the underpass, and the buildings that can be surveyed from its roof.

But even without such a deep recognition of the space… which, ultimately, soon comes to diverge from reality and take on a different – darker, otherworldly – feel… there’s a magic to the writing of this story. The reader is teased with just enough backstory to provide a compelling narrative without breaking the first-person illusion. No matter how many times you play (and I’ve played quite a few!), you’ll be left with a hole of unanswered questions, and you’ll need to be comfortable with that to get the most out of the story, but that in itself is an important part of the adventure. This is a story of a young person who doesn’t – who can’t – know everything that they need to bring them comfort in the (literally and figuratively) cold and disquieting world that surrounds them, and it’s a world that’s presented with a touching and tragic beauty.

Through multiple playthroughs – or rewinds, which it took me a while to notice were an option! – you’ll find yourself teased with more and more of the story. There are a few frankly-unfair moments where an unsatisfactory ending comes with little or no warning, and a handful of places where it feels like your choices are insignificant to the story, but these are few and far between. Altogether this is among the better pieces of hypertext fiction I’ve enjoyed, and I’d recommend that you give it a try (even if you don’t share the love-hate relationship with Preston Bus Station that is so common among those who spent much of their youth sitting in it).

It’s no secret that I spent a significant proportion of my youth waiting for or changing buses at (the remarkable) Preston Bus Station, and that doubtless biases my enjoyment of this game by tingeing it with nostalgia. But I maintain that it’s a well-written piece of hypertext interactive fiction with a rich, developed world. You can play it starting from here, and you should. It looks like the story’s accompanying images died somewhere along the way, but you can flick through them all here and get a feel for the shadowy, brutalist, imposing place.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

I can’t get enough of this comic. Despite the fact that it’s got no written dialogue at all I must’ve read it half a dozen times and seen more in it each time. Go read the whole thing…

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

My nephew, Michael, died on 22 May 2019. He was 15 years old.

He loved his family, tractors, lorries, tanks, spaceships and video games (mostly about tractors, lorries, tanks and spaceships), and confronted every challenge in his short, difficult life with a resolute will that earned him much love and respect. Online in his favourite game, Elite Dangerous by Frontier Developments, he was known as CMDR Michael Holyland.

In Michael’s last week of life, thanks to the Elite Dangerous player community, a whole network of new friends sprang up in our darkest hour and made things more bearable with a magnificent display of empathy, kindness and creativity. I know it was Michael’s wish to celebrate the generosity he was shown, so I’ve written this account of how Frontier and friends made the intolerable last days of a 15-year-old boy infinitely better.

…

I’m not crying, you’re crying.

A beautiful article which, despite its tragedy, does an excellent job of showcasing how video gaming communities can transcend barriers of distance, age, and ability and bring joy to the world. I wish that all gaming communities could be this open-minded and caring, and that they could do so more of the time.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Yaz writes, by way of partial explanation:

You could fit almost the entire history of videogames into the time span covered by the silent film era, yet we consider it a mature medium, rather than one just breaking out of its infancy. Like silent movies, classic games are often incomplete, damaged, or technically limited, but have a beauty all their own. In this spirit, indie game developer Joe Blair and I built Metropoloid, a remix of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis which replaces its famously lost score with that of its contemporaries from the early days of games.

I’ve watched Metropolis a number of times over the decades, in a variety of the stages of its recovery, and I love it. I’ve watched it with a pre-recorded but believed-to-be-faithful soundtrack and I’ve watched it with several diolive accompaniment. But this is the first time I’ve watched it to the soundtrack of classic (and contemporary-retro) videogames: the Metroid, Castlevania, Zelda, Mega Man and Final Fantasy series, Doom, Kirby, F-Zero and more. If you’ve got a couple of hours to spare and a love of classic film and classic videogames, then you’re in the slim minority that will get the most out of this fabulous labour of love (which, at the time of my writing, has enjoyed only a few hundred views and a mere 26 “thumbs up”: it certainly deserves a wider audience!).