I’ve generally been pretty defensive of Microsoft Edge, the default web browser in Windows 10. Unlike its much-mocked predecessor Internet Explorer, Edge is fast, clean, modern, and boasts good standards-compliance: all of the things that Internet Explorer infamously failed at! I was genuinely surprised to see Edge fail to gain a significant market share in its first few years: it seemed to me that everyday Windows users installed other browsers (mostly Chrome, which is causing its own problems) specifically because Internet Explorer was so terrible, and that once their default browser was replaced with something moderately-good this would no longer be the case. But that’s not what’s happened. Maybe it’s because Edge’s branding is too-remiscient of its terrible predecessor or maybe just because Windows users have grown culturally-used to the idea that the first thing they should do on a new PC is download a different browser, but whatever the reason, Edge is neglected. And for the most part, I’ve argued, that’s a shame.

But I’ve changed my tune this week after doing some research that demonstrates that a long-standing security issue of Internet Explorer is alive and well in Edge. This particular issue, billed as a “feature” by Microsoft, is deliberately absent from virtually every other web browser.

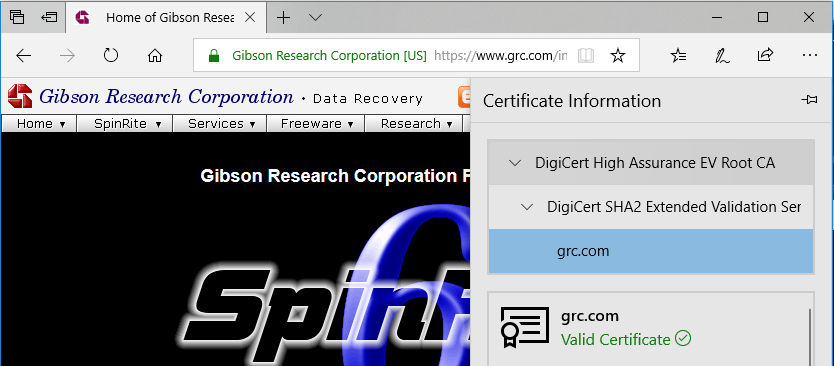

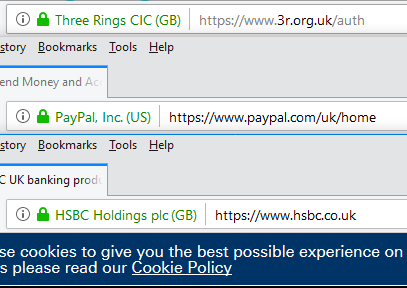

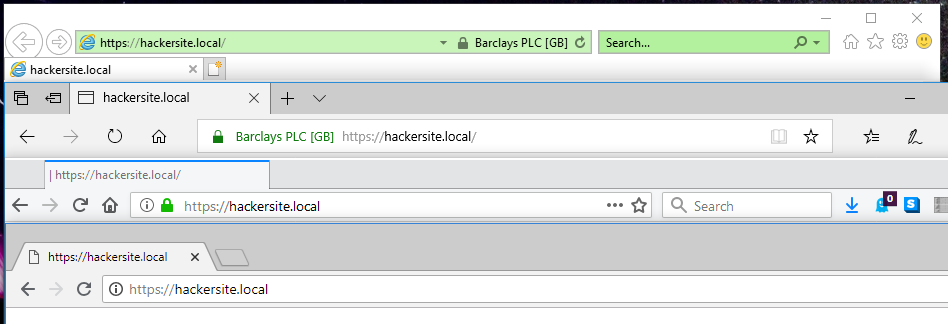

About 5 years ago, Steve Gibson observed a special feature of EV (Extended Validation) SSL certificates used on HTTPS websites: that their extra-special “green bar”/company name feature only appears if the root CA (certificate authority) is among the browser’s default trust store for EV certificate signing. That’s a pretty-cool feature! It means that if you’re on a website where you’d expect to see a “green bar”, like Three Rings, PayPal, or HSBC, then if you don’t see the green bar one day it most-likely means that your connection is being intercepted in the kind of way I described earlier this year, and everything you see or send including passwords and credit card numbers could be at risk. This could be malicious software (or nonmalicious software: some antivirus software breaks EV certificates!) or it could be your friendly local network admin’s middlebox (you trust your IT team, right?), but either way: at least you have a chance of noticing, right?

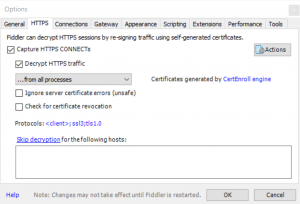

Browsers requiring that the EV certificate be signed by a one of a trusted list of CAs and not allowing that list to be manipulated (short of recompiling the browser from scratch) is a great feature that – were it properly publicised and supported by good user interface design, which it isn’t – would go a long way to protecting web users from unwanted surveillance by network administrators working for their employers, Internet service providers, and governments. Great! Except Internet Explorer went and fucked it up. As Gibson reported, not only does Internet Explorer ignore the rule of not allowing administrators to override the contents of the trusted list but Microsoft even provides a tool to help them do it!

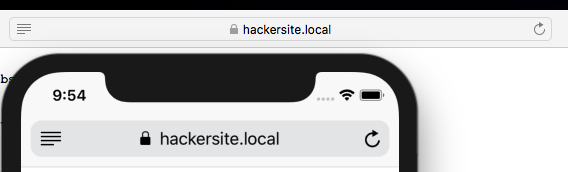

I decided to replicate Gibson’s experiment to confirm his results with today’s browsers: I was also interested to see whether Edge had resolved this problem in Internet Explorer. My full code and configuration can be found here. As is doubtless clear from the title of this post and the screenshot above, Edge failed the test: it exhibits exactly the same troubling behaviour as Internet Explorer.

Thanks, Microsoft.

I shan’t for a moment pretend that our current certification model isn’t without it’s problems – it’s deeply flawed; more on that in a future post – but that doesn’t give anybody an excuse to get away with making it worse. When it became apparent that Internet Explorer was affected by the “feature” described above, we all collectively rolled our eyes because we didn’t expect better of everybody’s least-favourite web browser. But for Edge to inherit this deliberate-fault, despite every other browser (even those that share its certificate store) going in the opposite direction, is just insulting.