I’ve tried a variety of unusual strategies to combat email spam over the years.

Here are some of them (each rated in terms the geekiness of its implementation and its efficacy), in case you’d like to try any yourself. They’re all still in use in some form or

another:

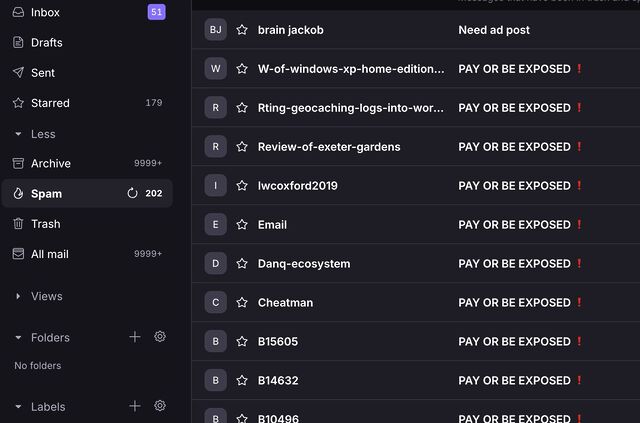

Spam filters

Geekiness: 1/10

Efficacy: 5/10

Your email provider or your email software probably provides some spam filters, and they’re probably pretty good. I use Proton‘s

and, when I’m at my desk, Thunderbird‘s. Double-bagging your spam filter only slightly reduces the amount of spam

that gets through, but increases your false-positive rate and some non-spam gets mis-filed.

A particular problem is people who email me for help after changing their name on FreeDeedPoll.org.uk, probably

because they’re not only “new” unsolicited contacts to me but because by definition many of them have strange and unusual names (which is why they’re emailing me for help in the first

place).

Frankly, spam filters are probably enough for many people. Spam filtering is in general much better today than it was a decade or two ago. But skim the other suggestions in

case they’re of interest to you.

Unique email addresses

Geekiness: 3/10

Efficacy: 8/10

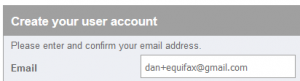

If you give a different email address to every service you deal with, then if one of them misuses it (starts spamming you, sells your data, gets hacked, whatever), you can just block

that one address. All the addresses come to the same inbox, for your convenience. Using a catch-all means that you can come up with addresses on-the-fly: you can even fill a paper

form with a unique email address associated with the company whose form it is.

On many email providers, including the ever-popular GMail, you can do this using plus-sign notation. But if you want to take your unique addresses to the next level and you have your own domain name (which you should), then you can simply redirect all email addresses on that domain to the same inbox. If Bob’s Building Supplies

wants your email address, give them bobs@yourname.com, which works even if Bob’s website erroneously doesn’t accept email addresses with plus signs in them.

This method actually works for catching people misusing your details. On one occasion, I helped a band identify that their mailing list had been hacked. On another, I caught a

dodgy entrepreneur who used the email address I gave to one of his businesses without my consent to send marketing information of a different one of his businesses. As a bonus, you can

set up your filtering/tagging/whatever based on the incoming address, rather than the sender, for the most accurate finding, prioritisation, and blocking.

Also, it makes it easy to have multiple accounts with any of those services that try to use the uniqueness of email addresses to prevent you from doing so. That’s great if, like me, you

want to be in each of three different Facebook groups but don’t want to give Facebook any information (not even that you exist at the intersection of those groups).

Signed unique email addresses

Geekiness: 10/10

Efficacy: 2/10

Unique email addresses introduce two new issues: (1) if an attacker discovers that your Dreamwidth account has the email address dreamwidth@yourname.com, they can

probably guess your LinkedIn email, and (2) attackers will shotgun “likely” addresses at your domain anyway, e.g. admin@yourname.com,

management@yourname.com, etc., which can mean that when something gets through you get a dozen copies of it before your spam filter sits up and takes notice.

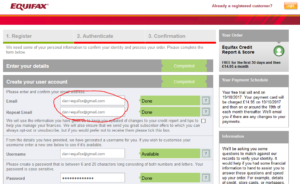

What if you could assign unique email addresses to companies but append a signature to each that verified that it was legitimate? I came up with a way to do this and

implemented it as a spam filter, and made a mobile-friendly webapp to help generate the necessary signatures. Here’s what it looked like:

- The domain directs all emails at that domain to the same inbox.

- If the email address is on a pre-established list of valid addresses, that’s fine.

- Otherwise, the email address must match the form of:

- A string (the company name), followed by

- A hyphen, followed by

-

A hash generated using the mechanism described below, then

- The @-sign and domain name as usual

The hashing algorithm is as follows: concatenate a secret password that only you know with a colon then the “company name” string, run it through SHA1, and truncate to the first eight characters. So if my password were swordfish1 and I were generating a password for Facebook, I’d go:

-

SHA1 ( swordfish1 : facebook) [ 0 ... 8 ] = 977046ce

- Therefore, the email address is

facebook-977046ce@myname.com

- If any character of that email address is modified, it becomes invalid, preventing an attacker from deriving your other email addresses from a single point (and making it

hard to derive them given multiple points)

I implemented the code, but it soon became apparent that this was overkill and I was targeting the wrong behaviours. It was a fun exercise, but ultimately pointless. This is the one

method on this page that I don’t still use.

Honeypots

Geekiness: 8/10

Efficacy: ?/10

A honeypot is a “trap” email address. Anybody who emails it get aggressively marked as a spammer to help ensure that any other messages they send – even to valid email

addresses – also get marked as spam.

I litter honeypots all over the place (you might find hidden email addresses on my web pages, along with text telling humans not to use them), but my biggest source of

honeypots is formerly-valid unique addresses, or “guessed” catch-all addresses, which already attract spam or are otherwise compromised!

I couldn’t tell you how effective it is without looking at my spam filter’s logs, and since the most-effective of my filters is now outsourced to Proton, I don’t have easy access to

that. But it certainly feels very satisfying on the occasions that I get to add a new address to the honeypot list.

Instant throwaways

Geekiness: 5/10

Efficacy: 6/10

OpenTrashmail is an excellent throwaway email server that you can deploy in seconds with Docker, point some MX records at, and be all set! A throwaway email server gives you an infinite number of unique email addresses, like other solutions described

above, but with the benefit that you never have to see what gets sent to them.

If you offer me a coupon in exchange for my email address, it’s a throwaway email address I’ll give you. I’ll make one up on the spot with one of my (several) trashmail domains at the

end of it, like justgivemethedamncoupon@danstrashmailserver.com. I can just type that email address into OpenTrashmail to see what you sent me, but then I’ll never check it

again so you can spam it to your heart’s content.

As a bonus, OpenTrashmail provides RSS feeds of inboxes, so I can subscribe to any email-based service using my feed reader,

and then unsubscribe just as easily (without even having to tell the owner).

Summary

With the exception of whatever filters your provider or software comes with, most of these options aren’t suitable for regular folks. But you’re only a domain name (assuming you don’t

have one already) away from being able to give unique email addresses to everybody you deal with, and that’s genuinely a game-changer all by itself and well worth considering, in my

opinion.