This post1 is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024.2Today’s prompt is:

Think back on your most memorable road trip.

Runners-up

It didn’t take me long to choose a most-memorable road trip, but first: here’s a trio of runners-up that I considered3:

-

A midwinter ascent

On the last day of 2018, Ruth‘s brother Robin and I made a winter ascent of Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in the British Isles. But amazing as the experience was, it perhaps wasn’t as memorable as the endless car journey up there, especially for Robin who was sandwiched between our two children in the back of the car and spent the entire 12-hour journey listening to Little Baby Bum songs on loop.4 Surely a quick route to insanity.

-

A childhood move

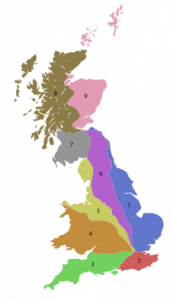

Shortly after starting primary school my family and I moved from Aberdeen, Scotland to the North-West of England. At my young age, long car journeys – such as those we’d had to make to view prospective new houses – always seemed interminably boring, but this one was unusually full of excitement and anticipation. The car was filled to the brim with everything we needed most-imminently to start our new lives5, while the removals lorry followed a full day behind us with everything less-essential6. I’m sure that to my parents it was incredibly stressful, but for me it was the beginning of an amazing voyage into the unknown.

-

Live on Earth

Back in 1999 I bought tickets for myself and two friends for Craig Charles’ appearance in Aberystwyth as part of his Live on Earth tour. My two friends shared a birthday at around the date of the show and had expressed an interest in visiting me, so this seemed like a perfect opportunity. Unfortunately I hadn’t realised that at that very moment one of them was preparing to have their birthday party… 240 miles away in London. In the end all three of us (plus a fourth friend who volunteered to be and overnight/early morning post-nightclub driver) attended both events back to back! A particular highlight came at around 4am we returned from a London nightclub to the suburb where we’d left the car to discover it was boxed in by some inconsiderate parking: we were stuck! So we gathered some strong-looking fellow partygoers… and carried the culprit’s car out of the way7. By that point we decided to go one step further and get back at its owner by moving their car around the corner from where they’d parked it. I reflected on parts of this anecdote back in 2010.

The winner

At somewhere between 500 and 600 road miles each way, perhaps the single longest road journey I’ve ever made without an overnight break was to attend a wedding.

The wedding was of my friends Kit and Fi, and took place a long, long way up into Scotland. At the time I (and a few other wedding guests) lived on the West coast of Wales. The journey options between the two might be characterised as follows:

- the fastest option: a train, followed by a ludicrously expensive plane, followed by a taxi

- the public transport option: about 16 hours of travel via a variety of circuitous train routes, but at least you get to sleep some of the way

- drive along a hundred miles of picturesque narrow roads, then three hundred of boring motorways, then another hundred and fifty of picturesque narrow roads

Guess which approach this idiot went for?

Despite having just graduated, I was still living very-much on a student-grade budget. I wasn’t confident that we could afford both the travel to and from the wedding and more than a single night’s accommodation at the other end.

But there were four of us who wanted to attend: me, my partner Claire, and our friends Bryn and Paul. Two of the four were qualified to drive and could be insured on Claire’s car8. This provided an opportunity: we’d make the entire 11-or-so-hour journey by car, with a pair of people sleeping in the back while the other pair drove or navigated!

It was long, and it was arduous, but we chatted and we sang and we saw a frankly ludicrous amount of the A9 trunk road and we made it to and from what was a wonderful wedding on our shoestring budget. It’s almost a shame that the party was so good that the memories of the road trip itself pale, or else this might be a better anecdote! But altogether, entirely a worthwhile, if crazy, exercise.

Footnotes

1 Participating in Bloganuary has now put me into my fifth-longest “daily streak” of blog posts! C-c-c-combo continues!

2 Also, wow: thanks to staying up late with my friend John drinking and mucking about with the baby grand piano in the lobby of the hotel we’re staying at, I might be first to publish a post for today’s Bloganuary!

3 Strangely, all three of the four journeys I’ve considered seem to involve Scotland. Which I suppose shouldn’t be too much of a surprise, given its distance from many of the other places I’ve lived and of course its size (and sometimes-sparse road network).

4 Okay, probably not for the entire journey, but I’m certain it must’ve felt like it.

5 Our cargo included several cats who almost-immediately escaped from their cardboard enclosures and vomited throughout the vehicle.

6 This included, for example, our beds: we spent our first night in our new house camped together in sleeping bags on the floor of what would later become my bedroom, which only added to the sense of adventure in the whole enterprise.

7 It was, fortunately, only a light vehicle, plus our designated driver was at this point so pumped-up on energy drinks he might have been able to lift it by himself!

8 It wasn’t a big car, and in hindsight cramming four people into it for such a long journey might not have been the most-comfortable choice!