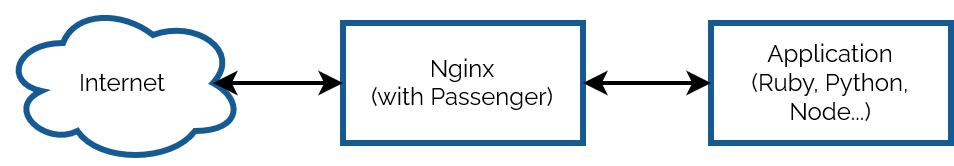

Do you remember when your domestic ISP – Internet Service Provider – used to be an Internet Services Provider? They were only sometimes actually called that, but what I mean is: when ISPs provided more than one Internet service? Not just connectivity, but… more.

ISPs twenty years ago

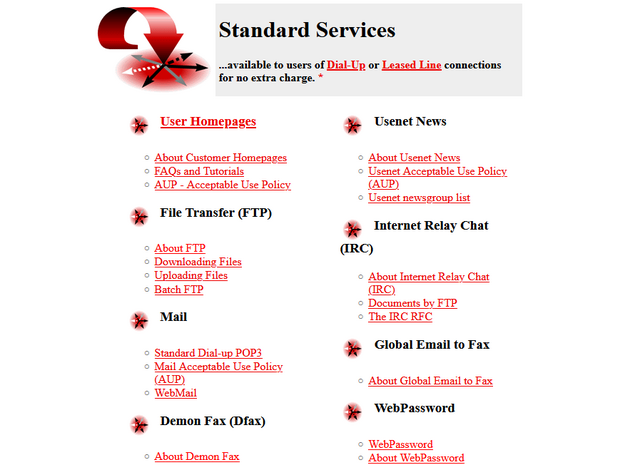

It used to just be expected that your ISP would provide you with not only an Internet connection, but also some or all of:

- A handful of email inboxes, plus SMTP relaying

- Shared or private FTP storage1

- Hosting for small Websites/homepages

- Usenet access

- Email-to-fax and/or fax-to-email services

- Caching forward proxies (this was so-commonplace that it isn’t even listed in the “standard services” screenshot above)

- One or more local nodes to IRC networks

- Sometimes, licenses for useful Internet software

- For leased-line (technically “broadband”, by the original definition) connections: a static IP address or IP pool

![Stylish (for circa 2000) webpage for HoTMetaL Pro 6.0, advertising its 'unrivaled [sic] editing, site management and publishing tools'.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2025/08/hotmetal-pro-6-640x396.jpg)

ISPs today

The ISP I hinted at above doesn’t exist any more, after being bought out and bought out and bought out by a series of owners. But I checked the Website of the current owner to see what their “standard services” are, and discovered that they are:

- A pretty-shit router2

- Optional 4G backup connectivity (for an extra fee)

- A voucher for 3 months access to a streaming service3

The connection is faster, which is something, but we’re still talking about the “baseline” for home Internet access then-versus-now. Which feels a bit galling, considering that (a) you’re clearly, objectively, getting fewer services, and (b) you’re paying more for them – a cheap basic home Internet subscription today, after accounting for inflation, seems to cost about 25% more than it did in 2000.4

Are we getting a bum deal?

Would you even want those services?

Some of them were great conveniences at the time, but perhaps not-so-much now: a caching server, FTP site, or IRC node in the building right at the end of my dial-up connection? That’s a speed boost that was welcome over a slow connection to an unencrypted service, but is redundant and ineffectual today. And if you’re still using a fax-to-email service for any purpose, then I think you have bigger problems than your ISP’s feature list!

Some of them were things I wouldn’t have recommend that you depend on, even then: tying your email and Web hosting to your connectivity provider traded one set of problems for another. A particular joy of an email address, as opposed to a postal address (or, back in the day, a phone number), is that it isn’t tied to where you live. You can move to a different town or even to a different country and still have the same email address, and that’s a great thing! But it’s not something you can guarantee if your email address is tied to the company you dial-up to from the family computer at home. A similar issue applies to Web hosting, although for a true traditional “personal home page”: a little information about yourself, and your bookmarks, it would be fine.

But some of them were things that were actually useful and I miss: honestly, it’s a pain to have to use a third-party service for newsgroup access, which used to be so-commonplace that you’d turn your nose up at an ISP that didn’t offer it as standard. A static IP being non-standard on fixed connections is a sad reminder that the ‘net continues to become less-participatory, more-centralised, and just generally more watered-down and shit: instead of your connection making you “part of” the Internet, nowadays it lets you “connect to” the Internet, which is a very different experience.5

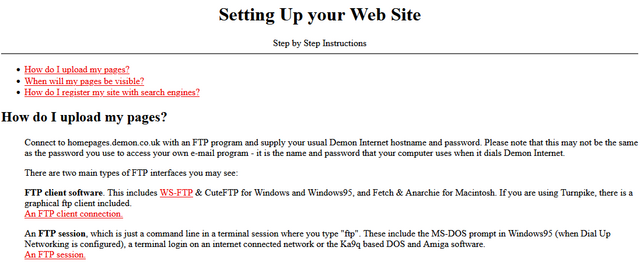

But the Web hosting, for example, wasn’t useless. In fact, it served an important purpose in lowering the barrier to entry for people to publish their first homepage! The magical experience of being able to just FTP some files into a directory and have them be on the Web, as just a standard part of the “package” you bought-into, was a gateway to a participatory Web that’s nowadays sadly lacking.

Yeah, sure, you can set up a static site (unencumbered by any opinionated stack) for free on Github Pages, Neocities, or wherever, but the barrier to entry has been raised by just enough that, doubtless, there are literally millions of people who would have taken that first step… but didn’t.

And that makes me sad.

Footnotes

1 ISP-provided shared FTP servers would also frequently provide locally-available copies of Internet software essentials for a variety of platforms. This wasn’t just a time-saver – downloading Netscape Navigator from your ISP rather than from half-way across the world was much faster! – it was also a way to discover new software, curated by people like you: a smidgen of the feel of a well-managed BBS, from the comfort of your local ISP!

2 ISP-provided routers are, in my experience, pretty crap 50% of the time… although they’ve been improving over the last decade as consumers have started demanding that their WiFi works well, rather than just works.

3 These streaming services vouchers are probably just a loss-leader for the streaming service, who know that you’ll likely renew at full price afterwards.

4 Okay, in 2000 you’d have also have had to pay per-minute for the price of the dial-up call… but that money went to BT (or perhaps Mercury or KCOM), not to your ISP. But my point still stands: in a world where technology has in general gotten cheaper and backhaul capacity has become underutilised, why has the basic domestic Internet connection gotten less feature-rich and more-expensive? And often with worse customer service, to boot.

5 The problem of your connection not making you “part of” the Internet is multiplied if you suffer behind carrier-grade NAT, of course. But it feels like if we actually cared enough to commit to rolling out IPv6 everywhere we could obviate the need for that particular turd entirely. And yet… I’ll bet that the ISPs who currently use it will continue to do so, even as the offer IPv6 addresses as-standard, because they buy into their own idea that it’s what their customers want.

6 I think we can all be glad that we no longer write “Web Site” as two separate words, but you’ll note that I still usually correctly capitalise Web (it’s a proper noun: it’s the Web, innit!).