This document was shared on my college Intranet and via a hidden URL on my first website, on 11 December 1997. It was republished here on 22 March 2021. It provides instructions for

players of the multiplayer DOOR game I adapted for local network play and the world I built within it for my friends to explore. The game world was an adaptation of our very own Preston

College but transplanted to a fantasy realm.

LEGEND OF THE RED DRAGON II – Preston College Version

You have probably been given this sheet because you have requested a chance to take part in one of the most fast-moving and user-interactive multi user games on earth. I’ve spent a lot

of time recently reprogramming Seth Able Robinson’s Bulletin Board System game, Legend Of The Red Dragon II (with his permission) to customise it and make it suitable for network play.

But – I’m sure this waffle is worthless to you; so here are the instructions you need:

To run the software:

Drop to an MS-DOS shell using the appropriate icon. Change to the ALEVEL.001 directory, if you’re not already there, by typing CD\ALEVEL.001.

Type PC (abbreviation of Preston College) to start. You will be asked for your user name and password. These should be on a slip of paper attached to the

foot of this sheet. Your password will be hidden from view for security.

Upon logging in for the first time you will see a menu from which you can choose to see the instructions, and other functions, or start the game. It is recommended that you read the

instructions now, though do remember it is possible to get to them from the game by tapping ?.

Assuming you’ve discovered how to play, by one means or another, here is a list of some people and places in the game you might want to visit.

(Please note : The map of Preston College in the game is only representative, and not necessarily accurate. There is most definitely not a cult temple or a stone circle on campus…)

ENROLMENT

Until you have visited here you won’t have a membership card, which allows you access to much of the game. It’s one of the first places your character should visit.

STUDENT SERVICES

Right next door to enrolment, this cool office will buy junk that you don’t want any more from you.

THE BEASTMAN

Kevin Geldard, your computing teacher, lives in an office on the Ground Floor of the Main Building. Though he can be prone to rambling on and persistently saying “BEAST!” in the middle

of otherwise sane-sounding sentences, he’s the key to a lot of the game world, and a valuable resource.

NETWORK SERVER

Found within the I.T. Block, this machine is the hub of all the computers in the college. With it it’s possible to really screw up somebody’s student record. However, it’s kept under

lock and key.

VENDING MACHINES

Keep your eye out for these, as you can buy food and drinks from them. Different foodstuffs restore different quantities of Hit Points, so try them all (remember that some also have

extra purposes beyond the obvious…)

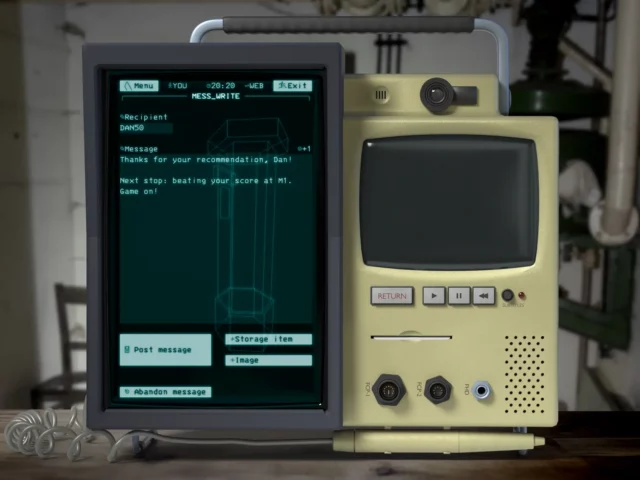

MESSAGE BOARDS

Scattered around the college, these appear as a coloured section of wall. You can write messages on them to other players, to arrange trade, combat and other meetings.

SOUTHERN PATH AND SAVICK BROOK

This dirt path, found beyond the amphitheatre, is a dangerous land. Head to it to practice your combat skills, and earn a little money and experience while you’re at it. The brook is a

barrier, protecting the campus from the Lands Of Chaos beyond. It is possible to cross the river at the bridge, but only the greatest warriors are allowed across.

TEMPLE OF NIG

The Disciples of Nig, a religious cult, have established themselves within the campus. Finding their temple will enable you to meditate there. Check the daily College Bulletin (by

pressing D) to find out if the Disciples are celebrating a festival to determine if it is worth your while to go there.

STONE CIRCLE

It is believed that the black altar within this strange circle of standing stones is blessed with a power beyond that of this world.

REFECTORY

This safe haven is a land of protection from other players. Take refuge here to escape the blows of your enemies. Just remember that you need your Student ID Card to get in.

NESCAFE BAR

The place to hang out if you’re waiting for somebody. Right next to a message board, and with easy access to the main doors, you can settle down here if you don’t quite require the

level of security the refectory provides.

![Stylish (for circa 2000) webpage for HoTMetaL Pro 6.0, advertising its 'unrivaled [sic] editing, site management and publishing tools'.](https://bcdn.danq.me/_q23u/2025/08/hotmetal-pro-6-640x396.jpg)