Well, Cape Town, you were a blast. But now it’s time to get back to my normal life for a bit.

🇿🇦✈️🇩🇪✈️🇬🇧

Well, Cape Town, you were a blast. But now it’s time to get back to my normal life for a bit.

🇿🇦✈️🇩🇪✈️🇬🇧

This is part of a series of posts on computer terminology whose popular meaning – determined by surveying my friends – has significantly diverged from its original/technical one. Read more evolving words…

Until the 17th century, to “fathom” something was to embrace it. Nowadays, it’s more likely to refer to your understanding of something in depth. The migration came via the similarly-named imperial unit of measurement, which was originally defined as the span of a man’s outstretched arms, so you can understand how we got from one to the other. But you know what I can’t fathom? Broadband.

Broadband Internet access has become almost ubiquitous over the last decade and a half, but ask people to define “broadband” and they have a very specific idea about what it means. It’s not the technical definition, and this re-invention of the word can cause problems.

High-speed, always-on Internet access.

Communications channel capable of multiple different traffic types simultaneously.

Throughout the 19th century, optical (semaphore) telegraph networks gave way to the new-fangled electrical telegraph, which not only worked regardless of the weather but resulted in

significantly faster transmission. “Faster” here means two distinct things: latency – how long it takes a message to reach its destination, and bandwidth – how much

information can be transmitted at once. If you’re having difficulty understanding the difference, consider this: a man on a horse might be faster than a telegraph if the size of the

message is big enough because a backpack full of scrolls has greater bandwidth than a Morse code pedal, but the latency of an electrical wire beats land transport

every time. Or as Andrew S. Tanenbaum famously put it: Never underestimate the bandwidth of a station wagon full of

tapes hurtling down the highway.

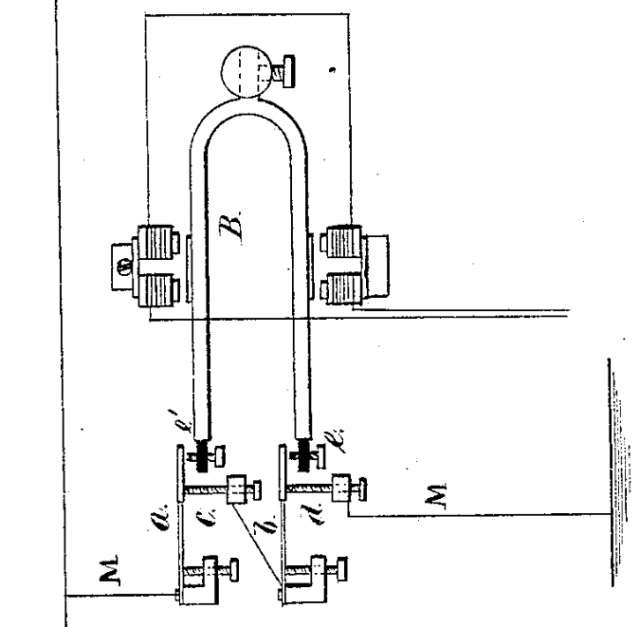

Telegraph companies were keen to be able to increase their bandwidth – that is, to get more messages on the wire – and this was achieved by multiplexing. The simplest approach, time-division multiplexing, involves messages (or parts of messages) “taking turns”, and doesn’t actually increase bandwidth at all: although it does improve the perception of speed by giving recipients the start of their messages early on. A variety of other multiplexing techniques were (and continue to be) explored, but the one that’s most-interesting to us right now was called acoustic telegraphy: today, we’d call it frequency-division multiplexing.

What if, asked folks-you’ll-have-heard-of like Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, we were to send telegraph messages down the line at different frequencies. Some beeps and bips would be high tones, and some would be low tones, and a machine at the receiving end could separate them out again (so long as you chose your frequencies carefully, to avoid harmonic distortion). As might be clear from the names I dropped earlier, this approach – sending sound down a telegraph wire – ultimately led to the invention of the telephone. Hurrah, I’m sure they all immediately called one another to say, our efforts to create a higher-bandwidth medium for telegrams has accidentally resulted in a lower-bandwidth (but more-convenient!) way for people to communicate. Job’s a good ‘un.

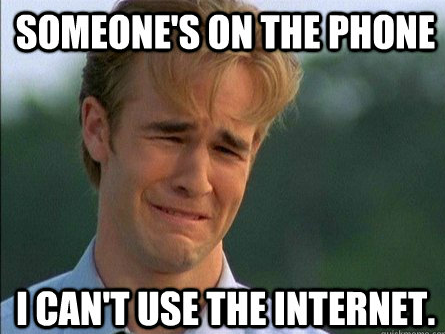

Most electronic communications systems that have ever existed have been narrowband: they’ve been capable of only a single kind of transmission at a time. Even if you’re multiplexing a dozen different frequencies to carry a dozen different telegraph messages at once, you’re still only transmitting telegraph messages. For the most part, that’s fine: we’re pretty clever and we can find workarounds when we need them. For example, when we started wanting to be able to send data to one another (because computers are cool now) over telephone wires (which are conveniently everywhere), we did so by teaching our computers to make sounds and understand one another’s sounds. If you’re old enough to have heard a fax machine call a landline or, better yet used a dial-up modem, you know what I’m talking about.

As the Internet became more and more critical to business and home life, and the limitations (of bandwidth and convenience) of dial-up access became increasingly questionable, a better solution was needed. Bringing broadband to Internet access was necessary, but the technologies involved weren’t revolutionary: they were just the result of the application of a little imagination.

We’d seen this kind of imagination before. Consider teletext, for example (for those of you too young to remember teletext, it was a standard for browsing pages of text and simple graphics using an 70s-90s analogue television), which is – strictly speaking – a broadband technology. Teletext works by embedding pages of digital data, encoded in an analogue stream, in the otherwise-“wasted” space in-between frames of broadcast video. When you told your television to show you a particular page, either by entering its three-digit number or by following one of four colour-coded hyperlinks, your television would wait until the page you were looking for came around again in the broadcast stream, decode it, and show it to you.

Teletext was, fundamentally, broadband. In addition to carrying television pictures and audio, the same radio wave was being used to transmit text: not pictures of text, but encoded characters. Analogue subtitles (which used basically the same technology): also broadband. Broadband doesn’t have to mean “Internet access”, and indeed for much of its history, it hasn’t.

Here in the UK, ISDN (from 1988!) and later ADSL would be the first widespread technologies to provide broadband data connections over the copper wires simultaneously used to carry telephone calls. ADSL does this in basically the same way as Edison and Bell’s acoustic telegraphy: a portion of the available frequencies (usually the first 4MHz) is reserved for telephone calls, followed by a no-mans-land band, followed by two frequency bands of different sizes (hence the asymmetry: the A in ADSL) for up- and downstream data. This, at last, allowed true “broadband Internet”.

But was it fast? Well, relative to dial-up, certainly… but the essential nature of broadband technologies is that they share the bandwidth with other services. A connection that doesn’t have to share will always have more bandwidth, all other things being equal! Leased lines, despite technically being a narrowband technology, necessarily outperform broadband connections having the same total bandwidth because they don’t have to share it with other services. And don’t forget that not all speed is created equal: satellite Internet access is a narrowband technology with excellent bandwidth… but sometimes-problematic latency issues!

Equating the word “broadband” with speed is based on a consumer-centric misunderstanding about what broadband is, because it’s necessarily true that if your home “broadband” weren’t configured to be able to support old-fashioned telephone calls, it’d be (a) (slightly) faster, and (b) not-broadband.

But does the word that people use to refer to their high-speed Internet connection matter. More than you’d think: various countries around the world have begun to make legal definitions of the word “broadband” based not on the technical meaning but on the populist one, and it’s becoming a source of friction. In the USA, the FCC variously defines broadband as having a minimum download speed of 10Mbps or 25Mbps, among other characteristics (they seem to use the former when protecting consumer rights and the latter when reporting on penetration, and you can read into that what you will). In the UK, Ofcom‘s regulations differentiate between “decent” (yes, that’s really the word they use) and “superfast” broadband at 10Mbps and 24Mbps download speeds, respectively, while the Scottish and Welsh governments as well as the EU say it must be 30Mbps to be “superfast broadband”.

I’m all in favour of regulation that protects consumers and makes it easier for them to compare products. It’s a little messy that definitions vary so widely on what different speeds mean, but that’s not the biggest problem. I don’t even mind that these agencies have all given themselves very little breathing room for the future: where do you go after “superfast”? Ultrafast (actually, that’s exactly where we go)? Megafast? Ludicrous speed?

What I mind is the redefining of a useful term to differentiate whether a connection is shared with other services or not to be tied to a completely independent characteristic of that connection. It’d have been simple for the FCC, for example, to have defined e.g. “full-speed broadband” as providing a particular bandwidth.

Verdict: It’s not a big deal; I should just chill out. I’m probably going to have to throw in the towel anyway on this one and join the masses in calling all high-speed Internet connections “broadband” and not using that word for all slower and non-Internet connections, regardless of how they’re set up.