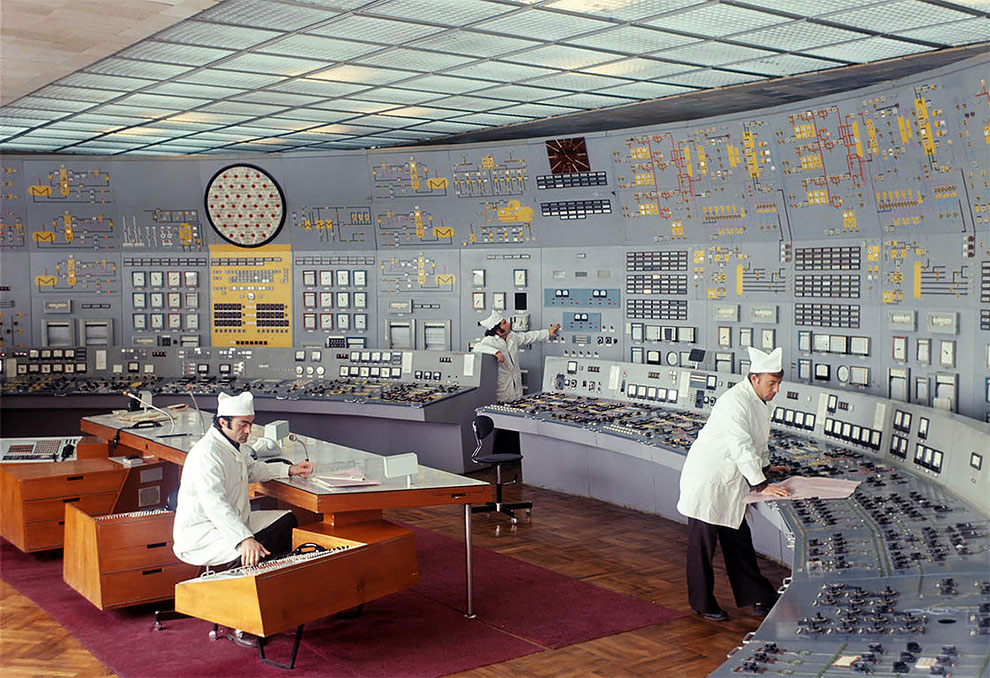

The Internet is full of commercial activity and it should come at no surprise that even illegal commercial activity is widespread as well. In this article we would like to describe

the current developments – from where we came, where we are now, and where it might be going – when it comes to technologies used for digital black market activity.

…

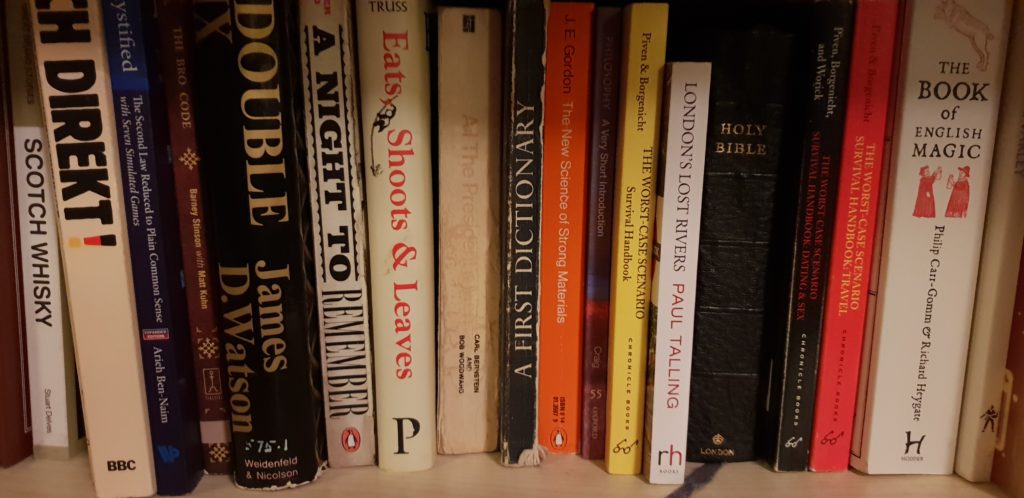

The other major change is the use of “dead drops” instead of the postal system which has proven vulnerable to tracking and interception. Now, goods are hidden in publicly accessible

places like parks and the location is given to the customer on purchase. The customer then goes to the location and picks up the goods. This means that delivery becomes asynchronous

for the merchant, he can hide a lot of product in different locations for future, not yet known, purchases. For the client the time to delivery is significantly shorter than waiting

for a letter or parcel shipped by traditional means – he has the product in his hands in a matter of hours instead of days. Furthermore this method does not require for the customer

to give any personally identifiable information to the merchant, which in turn doesn’t have to safeguard it anymore. Less data means less risk for everyone.

The use of dead drops also significantly reduces the risk of the merchant to be discovered by tracking within the postal system. He does not have to visit any easily to surveil post

office or letter box, instead the whole public space becomes his hiding territory.

…

From when I first learned about the existence of The Silk Road and its successors – places on the dark web where it’s possible to pseudo-anonymously make illicit purchases of e.g.

drugs, weapons, fake ID and the like in exchange for cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin – it always seemed to me that the weak point was that the “buyer” had to provide their postal address

to the “seller”. While there have, as this article describes, been a number of arrested made following postal inspections (especially as packages cross administrative boundaries), the

bigger risk I’d assume that this poses to the buyer is that they must trust the seller (who is, naturally, a bigger and more-interesting target) to appropriately secure and

securely-destroy that address information. In the event of a raid on a seller – or, indeed, law enforcement posing as a seller in a sting operation – the buyer is at

significant risk.

That risk may not be huge for Johnny Pothead who wants to buy an ounce of weed, but it rapidly scales up for “middleman” distributors who buy drugs in bulk, repackage, and resell either

on darknet markets or via conventional channels: these are obvious targets for law enforcement because their arrest disrupts the distribution chain and convictions are usually

relatively easy (“intent to supply” can be demonstrated in many jurisdictions by the volume of the product in which they’re found to be in possession). A solution to this problem, for

drug markets at least, with the fringe benefit of potentially faster-deliveries is pre-established dead drops (the downside, of course, is a more-limited geographical coverage and the

risk of discovery by a non-purchaser, but the latter of these can at least be mitigated), and it’s unsurprising to hear that this is the direction in which the ecosystem is moving. And

once you, Jenny Drugdealer, are putting that kind of infrastructure in place anyway, you might as well extend it to your regular clients too. So yeah: not surprising to see

things moving in this direction.

I recall that some years ago, a friend whom I’m introduced to geocaching accidentally ran across a dead drop (or a stash) while hunting for a ‘cache that was hidden in the same general

area. The stash was of clearly-stolen credit cards, and of course she turned it in to the police, but I think it’s interesting that these imaginative digital-era drug dealers, in trying

to improve upon a technique popularised by Cold War era spies by adding the capacity for long-time concealment of dead drops, are effectively re-inventing what the geocaching community

has been doing for ages.

What will they think of next? I’m betting drones.