RT @misterjta Dear 2012,

Fuck off. Sincerely, JTA.

Month: December 2012

Owl spreading its wings [x-post from /r/pics]

This link was originally posted to /r/thesuperbowl. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8063/8213230167_eca7b8b71b_o.jpg

Phone Security == Computer Security

The explosion of smartphone ownership over the last decade has put powerful multi-function computers into the pockets of almost half of us. But despite the fact that the average smartphone contains at least as much personally-identifiable information as its owner keeps on their home computer (or in dead-tree form) at their house – and is significantly more-prone to opportunistic theft – many users put significantly less effort into protecting their mobile’s data than they do the data they keep at home.

I have friends who religiously protect their laptops and pendrives with TrueCrypt, axCrypt, or similar, but still carry around an unencrypted mobile phone. What we’re talking about here is a device that contains all of the contact details for you and everybody you know, as well as potentially copies of all of your emails and text messages, call histories, magic cookies for social networks and other services, saved passwords, your browsing history (some people would say that’s the most-incriminating thing on their phone!), authentication apps, photos, videos… more than enough information for an attacker to pursue a highly-targeted identity theft or phishing attack.

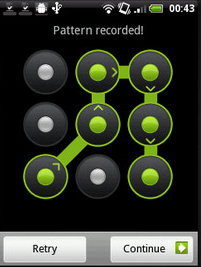

“Pattern lock” is popular because it’s fast and convenient. It might be good enough to stop your kids from using your phone without your permission (unless they’re smart enough to do some reverse smudge engineering: looking for the smear-marks made by your fingers as you unlock the device; and let’s face it, they probably are), but it doesn’t stand up to much more than that. Furthermore, gesture unlock solutions dramatically reduce the number of permutations, because you can’t repeat a digit: so much so, that you can easily perform a rainbow table attack on the SHA1 hash to reverse-engineer somebody’s gesture. Even if Android applied a per-device psuedorandom salt to the gesture pattern (they don’t, so you can download a prefab table), it doesn’t take long to generate an SHA1 lookup of just 895,824 codes (maybe Android should have listened to Coda Hale’s advice and used BCrypt, or else something better still).

These attacks, though (and the iPhone isn’t bulletproof, either), are all rather academic, because they are trumped by the universal rule that once an attacker has physical access to your device, it is compromised. This is fundamentally the way in which mobile security should be considered to be equivalent to computer security. All of the characteristics distinct to mobile devices (portability, ubiquity, processing power, etc.) are weaknesses, and that’s why smartphones deserve at least as much protection as desktop computers protecting the same data. Mobile-specific features like “remote wipe” are worth having, but can’t be relied upon alone – a wily attacker could easily keep your phone in a lead box or otherwise disable its connectivity features until it’s cracked.

The only answer is to encrypt your device (with a good password). Having to tap in a PIN or password may be less-convenient than just “swipe to unlock”, but it gives you a system that will resist even the most-thorough efforts to break it, given physical access (last year’s iPhone 4 vulnerability notwithstanding).

It’s still not perfect – especially here in the UK, where the RIPA can be used (and has been used) to force key surrender. What we really need is meaningful, usable “whole system” mobile encryption with plausible deniability. But so long as you’re only afraid of identity thieves and phishing scammers, and not being forced to give up your password by law or under duress, then it’s “good enough”.

Of course, it’s only any use if it’s enabled before your phone gets stolen! Like backups, security is one of those things that everybody should make a habit of thinking about. Go encrypt your smartphone; it’s remarkably easy –

- Android

- iPhone – just enable PIN lock, but consider also encrypting your backups

- BlackBerry

- Windows Phone – encryption is “coming soon”, apparently.

TIL that the Malaysian government is one of few who HAVEN’T asked Google to censor satellite photos of sensitive areas, because they feel that to do so would make it MORE obvious where the sensitive areas are!

This link was originally posted to /r/todayilearned. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: http://web.archive.org/web/20070509182328/http://www.nst.com.my/Current_News/nst/Wednesday/National/20070328080627/Article/local1_html

MALAYSIA will not ask Google Earth to blur images of the country’s military facilities to avoid terrorist attacks. Defence Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak said doing so would indirectly pin-point their location anyway.

“The difference in, or lack of, pixelation of images of the military facilities compared to the surrounding areas will make it easy for visual identification.” In his written reply to Datuk Dr James Dawos Mamit (BN-Mambong), Najib said the images were provided worldwide commercially.…

The Snip, Part 2

This is the second part of a three-part blog post about my vasectomy. Did you read the first part, yet?

My vasectomy was scheduled for Tuesday afternoon, so I left work early in order to cycle up to the hospital: my plan was to cycle up there, and then have Ruth ride my bike back while JTA drove me home. For a moment, though, I panicked the clinic receptionist when she saw me arrive carrying a cycle helmet and pannier bag: she assumed that I must be intending to cycle home after the operation!

It took me long enough to find the building, cycling around the hospital in the dark, and a little longer still to reassure myself that this underlit old building could actually be a place where surgery took place.

Despite my GP‘s suggestion to the contrary, the staff didn’t feel the need to take me though their counselling process, despite me ticking some (how many depends primarily upon how you perceive our unusual relationship structure) of the “we would prefer to counsel additionally” boxes on their list of criteria. I’d requested that Ruth arrive at about the beginning of the process specifically so that she could “back me up” if needed (apparently, surgeons will sometimes like to speak to the partner of a man requesting a vasectomy), but nobody even asked. I just had to sign another couple of consent forms to confirm that I really did understand what I was doing, and then I was ready to go!

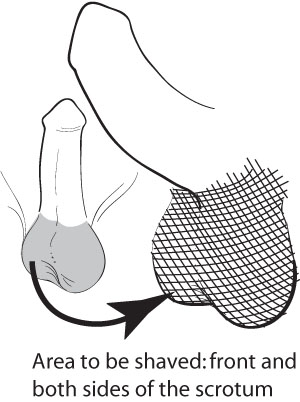

I’d shaved my balls a few days earlier, at the request of the clinic (and also at Matt‘s suggestion, who pointed out that “if I don’t, they’ll do it for me, and I doubt they’ll be as gentle!” – although it must be pointed out that as they were already planning to take a blade to my junk, I might not have so much to worry about), which had turned out to be a challenge in itself. I’ve since looked online and found lots of great diagrams showing you which parts you need to shave, but the picture I’d been given might as well have been a road map of Florence, because no matter which way up I turned it, it didn’t look anything like my genitals. In the end, I just shaved all over the damn place, just to be sure. Still not an easy feat, though, because the wrinkled skin makes for challenging shaving: the best technique I found was to “stretch” my scrotum out with one hand while I shaved it with the other – a tricky (and scary) maneuver.

After sitting in the waiting room for a while, I was ushered through some forms and a couple more questions of “are you sure?”, and then herded into a curtained cubicle to change into a surgical gown (over the top of which I wore my usual dressing gown). The floor was cold, and I’d forgotten to bring my slippers, so I kept my socks on throughout. I sat in a separate waiting area from the first, and attempted to make small talk with the other gents waiting there. Some had just come out of surgery, and some were still waiting to go in, and the former would gently tease the latter with jokes about the operation. It’s a man thing, I guess: I can’t imagine that women would be so likely to engage in such behaviour (ignoring, for a moment, the nature of the operation).

There are several different approaches to vasectomy, and my surgeon was kind enough to tolerate my persistent questions as I asked about the specifics of each part of the operation. He’d said – after I asked – that one of the things he liked about doing vasectomies was that (unlike most of the other surgeries he performs) his patients are awake and he can have a conversation while he worked, although I guess he hadn’t anticipated that there’d ever be anybody quite so interested as I was.

Warning: The remainder of this blog post describes a surgical procedure, which some people might find squicky. For the protection of those who are of a weak stomach, some photos have been hidden behind hyperlinks: click at your own risk. (though honestly, I don’t think they’re that bad)

With my scrotum pulled up through a hole in a paper sheet, the surgeon began by checking that “everything was where it was supposed to be”: he checked that he could find each vas (if you’ve not done this: borrow the genitals of the nearest man or use your own, squeeze moderately tightly between two fingers the skin above a testicle, and move around a bit until you find a hard tube: that’s almost certainly a vas). Apparently surgeons are supposed to take care to ensure that they’ve found two distinct tubes, so they don’t for example sever the same one twice.

Next, he gave the whole thing a generous soaking in iodine. This turned out to be fucking freezing. The room was cold enough already, so I asked him to close the window while my genitals quietly shivered above the sheet.

- Iodine-soaked scrotum being injected with anaesthetic (not mine; from a medical textbook)

Next up came the injection. The local anaesthetic used for this kind of operation is pretty much identical to the kind you get at the dentist: the only difference is that if your dentist injected you here, that’d be considered a miss. While pinching the left vas between his fingertips, the surgeon squirted a stack of lidocaine into the cavity around it. And fuck me, that hurt like being kicked in the balls. Seriously: that stung quite a bit for a few minutes, until the anaesthesia kicked in and instead the whole area felt “tingly”, in that way that your lips do after dental surgery.

- Vas clamp pulling the vas to the surface (not mine; from a medical textbook)

Pinching the vas (still beneath the skin at this point) in a specially-shaped clamp, the surgeon made a puncture wound “around” it with a sharp-nosed pair of forceps, and pulled the vas clean through the hole. This was a strange sensation – I couldn’t feel any pain, but I was aware of the movement – a “tugging” against my insides.

- Vas pulled through a hole (not mine; from a medical textbook)

A quick snip removed a couple of centimetres from the middle of it (I gather that removing a section, rather than just cutting, helps to reduce the – already slim – risk that the two loose ends will grow back together again) and cauterised the ends. The cauterisation was a curious experience, because while I wasn’t aware of any sensation of heat, I could hear a sizzling sound and smell my own flesh burning. It turns out that my flaming testicles smell a little like bacon. Or, if you’d like to look at it another way (and I can almost guarantee that you don’t): bacon smells a little bit like my testicles, being singed.

Next up came Righty’s turn, but he wasn’t playing ball (pun intended). The same steps got as far as clamping and puncturing before I suddenly felt a sharp pain, getting rapidly worse. “Ow… ow… owowowowowow!” I said, possibly with a little more swearing, as the surgeon blasted another few mils of anaesthetic into my bollocks. And then a little more. And damnit: it turns out that no matter how much you’ve had injected into you already, injecting anaesthetics into your tackle always feels like a kick in the nuts for a few minutes. Grr.

-

The removed sections of my vas, on a tray (actually mine)

You can see the “kink” in each, where it was pulled out by the clamp. Also visible is the clamp itself – a cruel-looking piece of equipment, I’m sure you’ll agree! – and the discarded caps from some of the syringes that were used.

The benefit of this approach, the “no-scalpel vasectomy”, is that the puncture wounds are sufficiently small as to not need stitches. At the end of the surgery, the surgeon just stuck a plaster onto the hole and called it done. I felt a bit light-headed and wobbly-legged, so I sat on the operating table for a few minutes to compose myself before returning to the nurses’ desk for my debrief. I only spent about 20 minutes, in total, with the surgeon: I’ve spent longer (and suffered more!) at the dentist.

By the evening, the anaesthetic had worn off and I was in quite a bit of pain, again: perhaps worse than that “kick in the balls” moment when the anaesthetic was first injected, but without the relief that the anaesthetic brought! I took some paracetamol and – later – some codeine, and slept with a folded-over pillow wedged between my knees, after I discovered how easy it was to accidentally squish my sore sack whenever I shifted my position.

The day after was somewhat better. I was walking like John Wayne, but this didn’t matter because – as the nurse had suggested – I spent most of the day lying down “with my feet as high as my bottom”. She’d taken the time to explain that she can’t put a bandage nor a sling on my genitals (and that I probably wouldn’t want her to, if she could), so the correct alternative is to wear tight-fitting underwear (in place of a bandage) and keep my legs elevated (as a sling). Having seen pictures of people with painful-looking bruises and swelling as a result of not following this advice, I did so as best as I could.

Today’s the day after that: I’m still in a little pain – mostly in Righty, again, which shall henceforth be called “the troublesome testicle” – but it’s not so bad except when I forget and do something like bend over or squat or, I discovered, let my balls “hang” under their own weight, at all. But altogether, it’s been not-too-bad at all.

Or, as I put on my feedback form at the clinic: “A+++. Recommended. Would vasectomy again.”

(thanks due to Ruth, JTA, Matt, Liz, Simon, Michelle, and my mum for support, suggestions, and/or fetching things to my bed for me while I’ve been waddling around looking like John Wayne, these past two days)