We’ve recently had the attics of our house converted, and I moved my bedroom up to one of the newly-constructed rooms.

To make the space my own, I did a little light carpentry up there: starting with a necessary reshaping of the doors, then moving on to shelving and eventually… a secret cabinet!

I’d love to tell you about how I built it: but first, a disclaimer! I am a software engineer, and with good reason. Letting me near a soldering iron is ill-advised. Letting me use a table saw is tempting fate.

Letting me teach you anything about how you should use a soldering iron or a table saw is, frankly, asking for trouble.

Building a secret cabinet wasn’t part of my plan, but came about naturally after I got started. I’d bought a stack of pine planks and – making use of Ruth’s table saw – cut them to squarely fit beneath each of the two dormer windows1. While sanding and oiling the wood I realised that I had quite a selection of similarly-sized offcuts and found myself wondering if I could find a use for them.

I figured I had enough lumber to insert a small cabinet into one of the bookshelves, and that got me thinking… what about if it were a secret cabinet, disguised as books unless you knew where to look. Or to go one step further: what if it had some kind of electronic locking mechanism that could be triggered from somewhere else in the room2.

Not wanting to destroy a stack of real books, which is the traditional way to get a collection of book spines for the purpose of decorating a “fake bookshelf” panel3, I looked online and discovered the company that made the fake book spines used at the shop of my former employer. They looked ideal: carefully shaped and painted panels with either an old-school or contemporary look.

Buuut, they don’t seem to be well-equipped for short runs and are doubtless pricey, so I looked elsewhere and found the eBay presence of Beatty Lockey Antiques in Loewstof. They’d acquired a stack of them second-hand from the set of Netflix’s The School for Good and Evil.4

(By the way: at time of writing they’ve still got a few panels left, if you want to make your own…)

The cabinet is just a few bits of wood glued together and reinforced with L-shaped corner braces, with a trio of thin strips – made from leftover architrave board – attached using small brass hinges. The fake book fronts are stuck to the strips using double-sided mounting tape left over from installing a bathroom mirror. A simple magnetic clasp holds the door shut when pushed closed5, and the hinges are inclined to “want” the door to stand half-open, which means it only needs a gentle push away from the magnetic catch to swing it open.

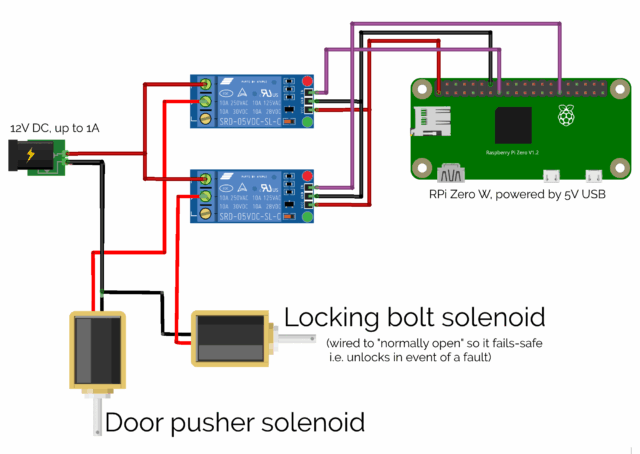

I mounted a Raspberry Pi Zero W into a rear corner inside the cabinet6, and wired it up via a relay to what was sold to me as a “large push-pull solenoid”, then began experimenting with the position in which I’d need to mount it to allow it to “kick” open the door, against the force of the magnetic clasp7.

This was, amazingly, the hardest part of the whole project! Putting the solenoid too close to the door didn’t work: it couldn’t “push” it from a standing start. Too far away, and the natural give of the door took the strain without pushing it open. Just the right distance, and the latch had picked up enough momentum that its weight “kicked” the door away from the magnet and followed-through to ensure that it kept moving.

A second solenoid, mounted inside the top of the cabinet, slides into the “loop” part of a large bolt fitting, allowing the cabinet to be electronically “locked”.

Next up came the software. I started with a very simple Python program8 that would run a webserver and, on particular requests, open the lock solenoid and push with the “kicker” solenoid.

#!/usr/bin/python # # a basic sample implementation of a web interface for a secret cabinet # # setup: # sudo apt install -y python3-flask # wget https://github.com/sbcshop/Zero-Relay/blob/master/pizero_2relay.py # # running: # sudo flask --app web run --host=0.0.0.0 --port 80 from flask import Flask, redirect, url_for import pizero_2relay as pizero from time import sleep # set up pizero_2relay with the two relays attached to this Pi Zero: r1 = pizero.relay("R1") # The "kicker" relay r2 = pizero.relay("R2") # The "locking bolt" relay app = Flask(__name__) # GET / - nothing here @app.route("/") def index(): return "Nothing to see here." # GET /relay - show a page with "open" and "lock" links @app.route("/relay") def relay(): return "<html><head><meta name='viewport' content='width=device-width, initial-scale=1'></head><body><ul><li><a href='/relay/open'>Open</a></li><li><a href='/relay/lock'>Lock</a></li></ul>" # GET /relay/open - open the secret cabinet then return to /relay # This ought to be a POST request in your implementation, and you probably # want to add some security e.g. a @app.route("/relay/open") def open(): # Retract the lock: r2.off() sleep(0.5) # Fire the kicker twice: r1.on() sleep(0.25) r1.off() sleep(0.25) r1.on() sleep(0.25) r1.off() # Redirect back: return redirect(url_for('relay')) @app.route("/relay/lock") def lock(): # Engage the lock: r2.on() return redirect(url_for('relay'))

Once I had something I could trigger from a web browser or with curl, I could start experimenting with trigger mechanisms. I had a few ideas (and prototyped a couple of

them), including:

- A mercury tilt switch behind a different book, so you pull it to release the cabinet in the style of a classic movie secret door.

- A microphone that listens for a specific pattern of knocks on a nearby surface.

- An RFID reader mounted underneath another surface, and a tag on the underside of an ornament: moving the ornament to the “right” place on the surface triggers the cabinet (elsewhere in the room).

- The current design, shown in the video above, where a code9 is transmitted to the cabinet for verification.

I think I’m happy with what I’ve got going on with it now. And it’s been a good opportunity to improve my carpentry, electronics, and Python.

Footnotes

1 The two dormer windows, wouldn’t you guarantee it, were significantly different widths despite each housing a window of the same width. Such are the quirks of extending a building that the previous occupier had previously half-heartedly tried to extend, I guess.

2 Why yes, I am a big fan of escape rooms. Why do you ask?

3 For one thing, I live with JTA, and I’m confident that he’d somehow be able to hear the silent screams of whatever trashy novels I opted to sacrifice for the good of the project.

4 As a bonus, my 10-year-old is a big fan of the book series that inspired the film (and a more-muted fan of the film itself) and she was ever-so excited at my project using real-life parts of the set of the movie… that she’s asked me to make a similar secret cabinet for her, when we get around to redecorating her room later in the year!

5 If I did it again, I might consider using a low-powered electromagnetic lock to hold the door shut. In this design, I used a permanent magnet and a pair of latch solenoids: one to operate a bolt, the second to “kick” the door open against the pull of the magnet, and… it feels a little clumsier than a magnetic lock might’ve.

6 That double-sided mounting tape really came in handy for this project!

7 Props to vlogger Technology Connections, one of whose excellent videos on the functionality of 1970s pinball tables – maybe this one? – taught me what a latch solenoid was in the first place, last year, which probably saved me from the embarrassment of trying to do this kind of thing with, I don’t know, a stepper motor or something.

8 I’m not a big fan of Python normally, but the people who made my relays had some up with a convenience library for them that was written in it, so I figured it would do.

9 Obviously the code isn’t A-B; I changed it temporarily for the video.