Following the success of our last game of Dialect the previous month and once again in a one-week hiatus of our usual Friday Dungeons & Dragons game, I hosted a second remote game of this strange “soft” RPG with linguistics and improv drama elements.

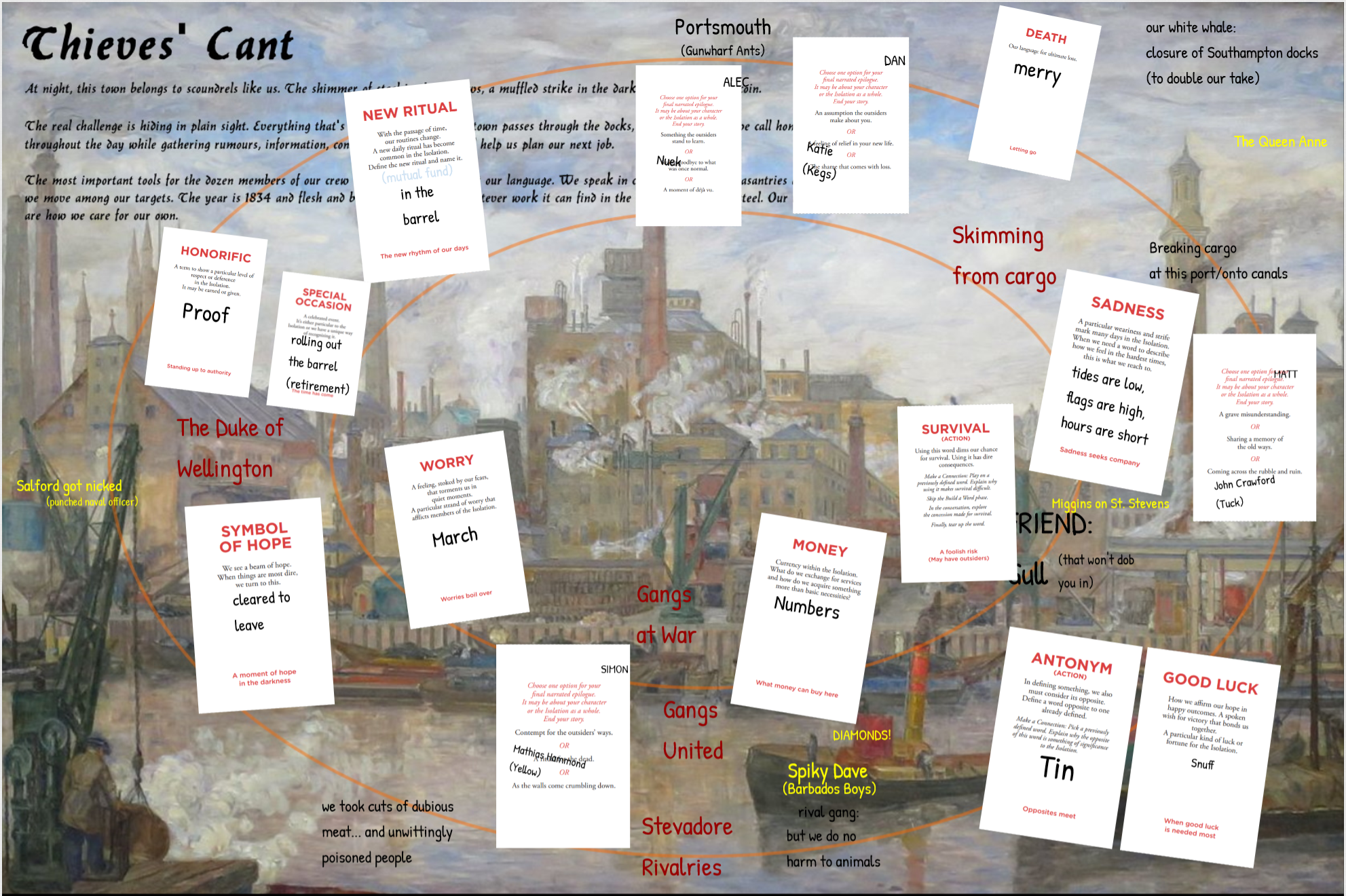

Thieves’ Cant

Our backdrop to this story was Portsmouth in 1834, where we were part of a group – the Gunwharf Ants – who worked as stevedores and made our living (on top of the abysmal wages for manual handling) through the criminal pursuit of “skimming a little off the top” of the bulk-break cargo we moved between ships and onto and off the canal. These stolen goods would be hidden in the basement of nearby pub The Duke of Wellington until they could be safely fenced, and this often-lucrative enterprise made us the envy of many of the docklands’ other criminal gangs.

I played Katie – “Kegs” to her friends – the proprietor of the Duke (since her husband’s death) and matriarch of the group. I was joined by Nuek (Alec), a Scandinavian friend with a wealth of criminal experience, John “Tuck” Crawford (Matt), adoptee of the gang and our aspiring quartermaster, and “Yellow” Mathias Hammond (Simon), a navy deserter who consistently delivers better than he expects to.

While each of us had our stories and some beautiful and hilarious moments, I felt that we all quickly converged on the idea that the principal storyline in our isolation was that of young Tuck. The first act was dominated by his efforts to proof himself to the gang, and – with a little snuff – shake off his reputation as the “kid” of the group and gain acceptance amongst his peers. His chance to prove himself with a caper aboard the Queen Anne went proper merry though after she turned up tin-ful and he found himself kept in a second-place position for years longer. Tuck – and Yellow – got proofed eventually, but the extra time spent living hand-to-mouth might have been what first planted the seed of charity in the young man’s head, and kept most of his numbers out of his pocket and into those of the families he supported in the St. Stevens area.

The second act turned political, as Spiky Dave, leader of the competing gang The Barbados Boys, based over Gosport way, offered a truce between the two rivals in exchange for sharing the manpower – and profits – of a big job against a ship from South Africa… with a case of diamonds aboard. Disagreements over the deal undermined Kegs’ authority over the Ants, but despite their March it went ahead anyway and the job was a success. Except… Spiky Dave kept more than his share of the loot, and agreed to share what was promised only in exchange for the surrender of the Ants and their territory to his gang’s rulership.

We returned to interpersonal drama in the third act as Katie – tired of the gang wars and feeling her age – took perhaps more than her fair share of the barrel (the gang’s shared social care fund) and bought herself clearance to leave aboard a ship to a beachside retirement in Jamaica. She gave up her stake in the future of the gang and shrugged off their challenges in exchange for a quiet life, leaving Nuek as the senior remaining leader of the group… but Tuck the owner of the Duke of Wellington. The gang split into those that integrated with their rivals and those that went their separate ways… and their curious pidgin dissolved with them. Well, except for a few terms which hung on in dockside gang chatter, screeched amongst the gulls of Portsmouth without knowing their significance, for years to come.

Playing Out

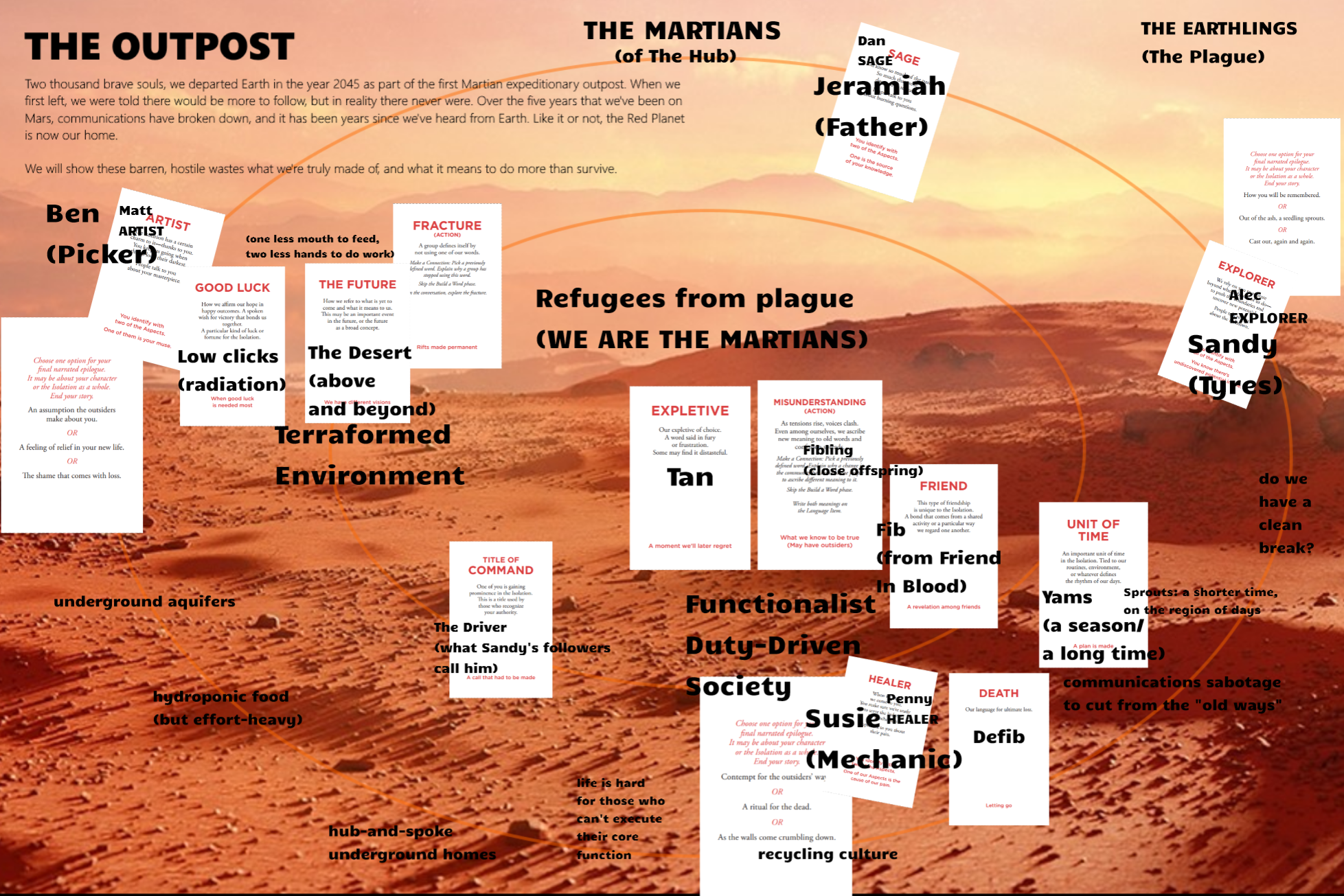

Despite being fundamentally the same game and a similar setting to when we played The Outpost the previous month, this game felt very different. Dialect is versatile enough that it can be used to write… adventures, coming-of-age tales, rags-to-riches stories, a comedies, horror, romance… and unless the tone is explicitly set out at the start then it’ll (hopefully) settle somewhere mutually-acceptable to all of the players. But with a new game, new setting, and new players, it’s inevitable that a different kind of story will be told.

But more than that, the backdrop itself impacted on the tale we wove. On Mars, we were physically isolated from the rest of humankind and living in an environment in which the necessities of a new lifestyle and society necessitates new language. But the isolation of criminal gangs in Portsmouth docklands in the late Georgian era is a very different kind: it’s a partial isolation, imposed (where it is) by its members and to a lesser extent by the society around them. Which meant that while their language was still a defining aspect of their isolation, it also felt more-artificial; deliberately so, because those who developed it did so specifically in order to communicate surreptitiously… and, we discovered, to encode their group’s identity into their pidgin.

While our first game of Dialect felt like the language lead the story, this second game felt more like the language and the story co-evolved but were mostly unrelated. That’s not necessarily a problem, and I think we all had fun, but it wasn’t what we expected. I’m glad this wasn’t our first experience of Dialect, because if it were I think it might have tainted our understanding of what the game can be.

As with The Outpost, we found that some of the concepts we came up with didn’t see much use: on Mars, the concept of fibs was rooted in a history of of how our medical records were linked to one another (for e.g. transplant compatibility), but aside from our shared understanding of the background of the word this storyline didn’t really come up. Similarly, in Thieves Cant’ we developed a background about the (vegan!) roots of our gang’s ethics, but it barely got used as more than conversational flavour. In both cases I’ve wondered, after the fact, whether a “flashback” scene framed from one of our prompts might have helped solidify the concept. But I’m also not sure whether or not such a thing would be necessary. We seemed to collectively latch onto a story hook – this time around, centred around Matt’s character John Crawford’s life and our influences on it – and it played out fine.

And hey; nobody died before the epilogue, this time!

I’m looking forward to another game next time we’re on a D&D break, or perhaps some other time.