Earlier this month, I received a phone call from a user of Three Rings, the volunteer/rota management software system I founded1.

We don’t strictly offer telephone-based tech support – our distributed team of volunteers doesn’t keep any particular “core hours” so we can’t say who’s available at any given time – but instead we answer email/Web based queries pretty promptly at any time of the day or week.

But because I’ve called-back enough users over the years, it’s pretty much inevitable that a few probably have my personal mobile number saved. And because I’ve been applying for a couple of interesting-looking new roles, I’m in the habit of answering my phone even if it’s a number I don’t recognise.

After the first three such calls this month, I was really starting to wonder what had changed. Had we accidentally published my phone number, somewhere? So when the fourth tech support call came through, today (which began with a confusing exchange when I didn’t recognise the name of the caller’s charity, and he didn’t get my name right, and I initially figured it must be a wrong number), I had to ask: where did you find this number?

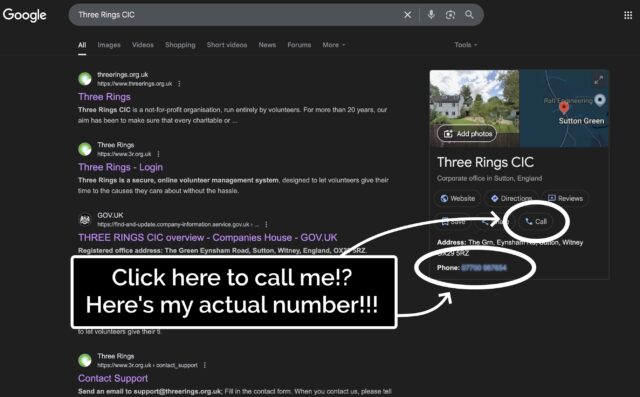

“When I Google ‘Three Rings login’, it’s right there!” he said.

He was right. A Google search that surfaced Three Rings CIC’s “Google Business Profile” now featured… my personal mobile number. And a convenient “Call” button that connects you directly to it.

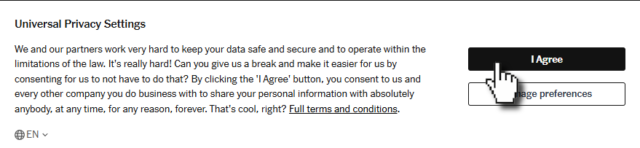

Some years ago, I provided my phone number to Google as part of an identity verification process, but didn’t consent to it being shared publicly. And, indeed, they didn’t share it publicly, until – seemingly at random – they started doing so, presumably within the last few weeks.

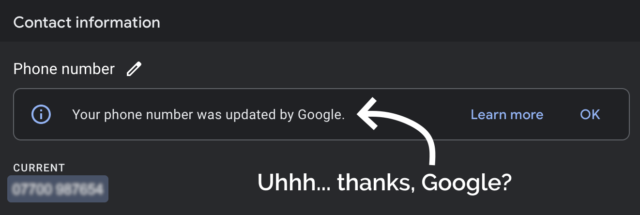

Concerned by this change, I logged into Google Business Profile to see if I could edit it back.

I deleted my phone number from the business listing again, and within a few minutes it seemed to have stopped being served to random strangers on the Internet. Unfortunately deleting the phone number also made the “Your phone number was updated by Google” message disappear, so I never got to click the “Learn more” link to maybe get a clue as to how and why this change happened.

Last month, high-street bank Halifax posted the details of a credit agreement I have with them to two people who aren’t me. Twice in two months seems suspicious. Did I accidentally click the wrong button on a popup and now I’ve consented to all my PII getting leaked everywhere?

Such feelings of rage.

Footnotes

1 Way back in 2002! We’re very nearly at the point where the Three Rings system is older than the youngest member of the Three Rings team. Speaking of which, we’re seeking volunteers to help expand our support team: if you’ve got experience of using Three Rings and an hour or two a week to spare helping to make volunteering easier for hundreds of thousands of people around the world, you should look us up!

2 Seriously: if you’re still using Google Search as your primary search engine, it’s past time you shopped around. There are great alternatives that do a better job on your choice of one or more of the metrics that might matter to you: better privacy, fewer ads (or more-relevant ads, if you want), less AI slop, etc.