Lacking a basis for comparison, children accept their particular upbringing as normal and representative.

Kit was telling me about how his daughter considers it absolutely normal to live in a house full of insectivorous plants1, and it got me thinking about our kids, and then about myself:

I remember once overhearing our eldest, then at nursery, talking to her friend. Our kid had mentioned doing something with her “mummy, daddy, and Uncle Dan” and was incredulous that her friend didn’t have an Uncle Dan that they lived with! Isn’t having three parents… just what a family looks like?

By the time she was at primary school, she’d learned that her family wasn’t the same shape as most other families, and she could code-switch with incredible ease. While picking her up from school, I overheard her talking to a friend about a fair that was coming to town. She told the friend that she’d “ask her dad if she could go”, then turned to me and said “Uncle Dan: can we go to the fair?”; when I replied in the affirmitive, she turned back and said “my dad says it’s okay”. By the age of 5 she was perfectly capable of translating on-the-fly2 in order to simultaneously carry out intelligble conversations with her family and with her friends. Magical.

When I started driving, and in particular my first few times on multi-lane carriageways, something felt “off” and it took me a little while to work out what it was. It turns out that I’d internalised a particular part of the motorway journey experience from years of riding in cars driven by my father, who was an unrepentant3 and perpetual breaker of speed limits.4 I’d come to associate motorway driving with overtaking others, but almost never being overtaken, but that wasn’t what I saw when I drove for myself.5 It took a little thinking before I realised the cause of this false picture of “what driving looks like”.

The thing is: you only ever notice the “this is normal” definitions that you’ve internalised… when they’re challenged!

It follows that there are things you learned from the quirks of your upbringing that you still think of as normal. There might even be things you’ll never un-learn. And you’ll never know how many false-normals you still carry around with you, or whether you’ve ever found them all, exept to say that you probably haven’t yet.

It’s amazing and weird to think that there might be objective truths you’re perpetually unable to see as a restult of how, or where, or by whom you were brought up, or by what your school or community was like, or by the things you’ve witnessed or experienced over your life. I guess that all we can all do is keep questioning everything, and work to help the next generation see what’s unusual and uncommon in their own lives.

Footnotes

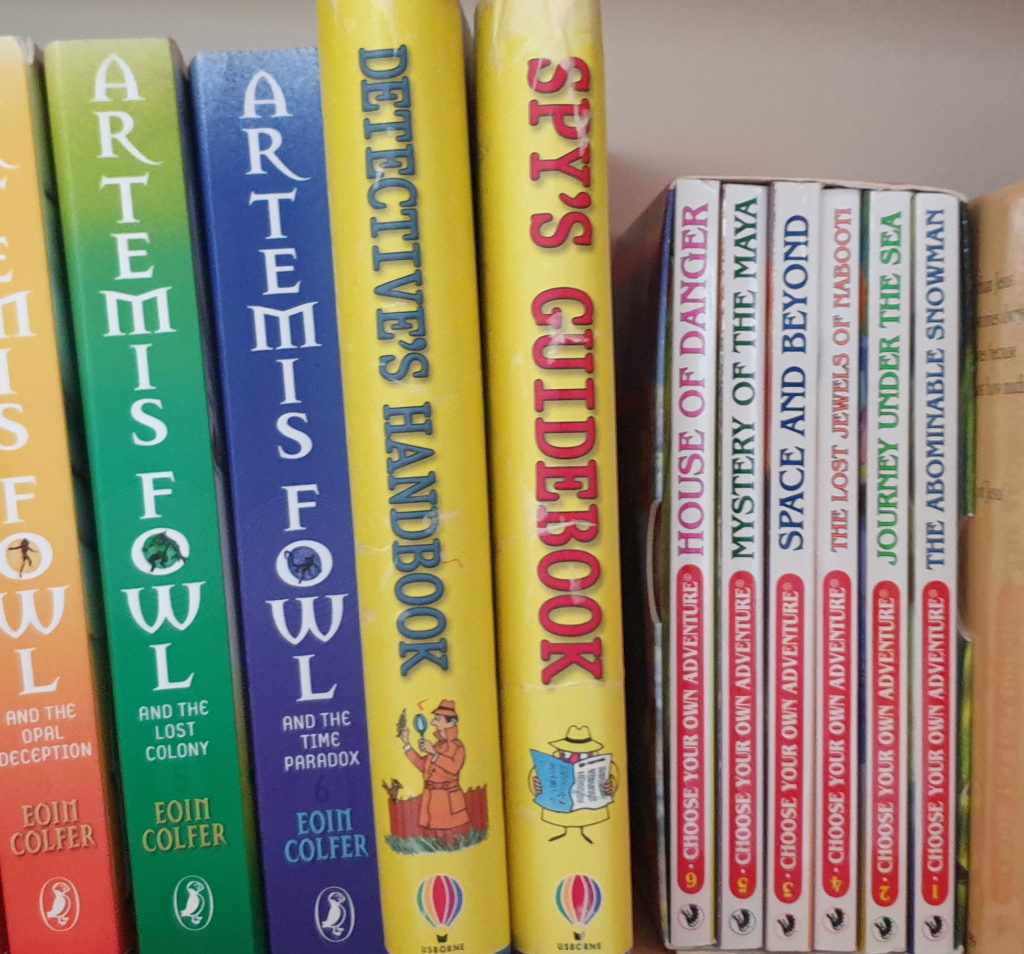

1 It’s a whole thing. If you know Kit, you’re probably completely unsurprised, but spare a thought for the poor randoms who sometimes turn up and read my blog.

2 Fully billingual children who typically speak a different language at home than they do at school do this too, and it’s even-more amazing to watch.

3 I can’t recall whether his license was confiscated on two or three separate ocassions, in the end, but it was definitely more than one. Having a six month period where you and your siblings have to help collect the weekly shop from the supermarket by loading up your bikes with shopping bags is a totally normal part of everybody’s upbringing, isn’t it?

4 Virtually all of my experience as a car passenger other than with my dad was in Wales, where narrow windy roads mean that once you get stuck behind something, that’s how you’re going to be spending your day.

5 Unlike my father, I virtually never break the speed limit, to such an extent that when I got a speeding ticket the other year (I’d gone from a 70 into a 50 zone and re-set the speed limiter accordingly, but didn’t bother to apply the brakes and just coasted down to the new speed… when the police snapped their photo!), Ruth and JTA both independently reacted to the news with great skepticism.