One of my favourite parts of my former role at the Bodleian Libraries was getting to work on exhibitions. Not just because it was varied and interesting work, but because it let me get up-close to remarkable artifacts that most people never even get the chance to see.

A personal favourite of mine are the Herculaneum Papyri. These charred scrolls were part of a private library near Pompeii that was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Rediscovered from 1752, these ~1,800 scrolls were distributed to academic institutions around the world, with the majority residing in Naples’ Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III.

As you might expect of ancient scrolls that got buried, baked, and then left to rot, they’re pretty fragile. That didn’t stop Victorian era researchers trying a variety of techniques to gently unroll them and read what was inside.

Like many others, what I love about the Herculaneum Papyri is the air of mystery. Each could be anything from a lost religious text to, I don’t know, somebody’s to-do list (“buy milk, arrange for annual service of chariot, don’t forget to renew volcano insurance…”).1

In recent years, we’ve tried “virtually unrolling” the scrolls using a variety of related technologies. And – slowly – we’re getting there.

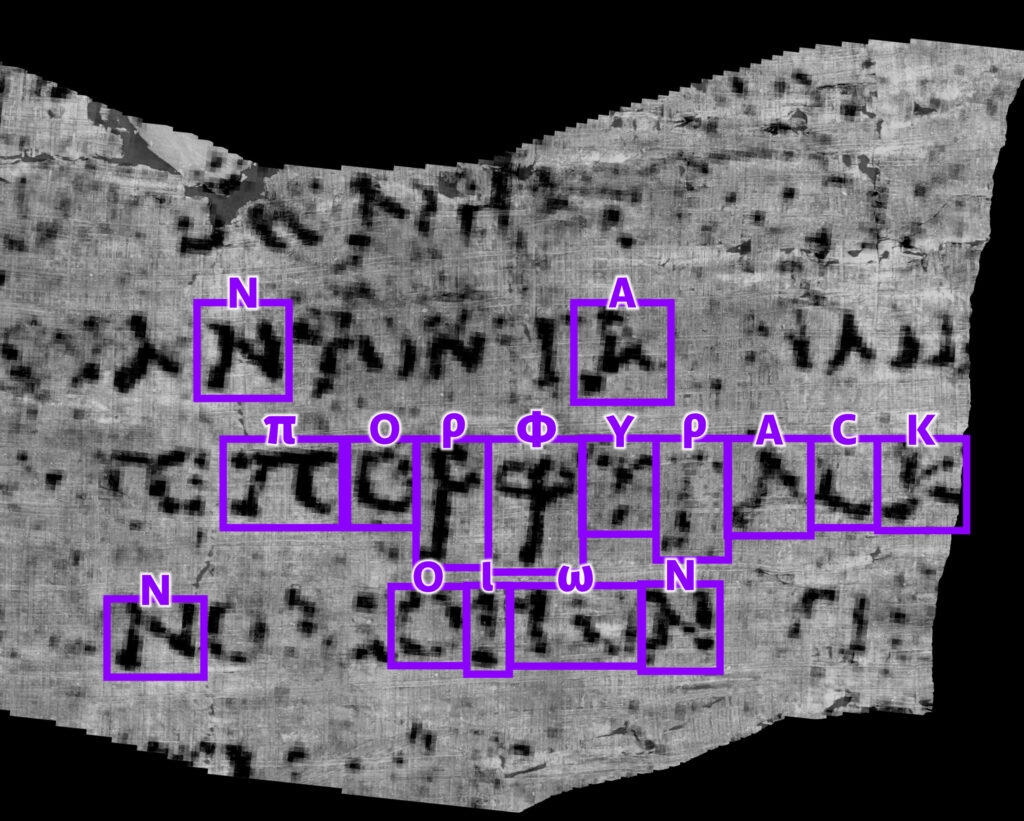

So imagine my delight when this week, for the first time ever, a complete word was extracted from one of the carbonised, still-rolled-up scrolls from Herculaneum. Something that would have seemed inconceivable to the historians who first discovered and catalogued the scrolls is now possible, thanks to their careful conservation over the years along with the steady advance of technology.

Footnotes

1 For more-serious academic speculation about the potential value of the scrolls, Richard Carrier’s got you covered.