I last handed in a dissertation almost 16 years ago; that one marked the cumulation of my academic work at Aberystwyth University, then the “University of Wales, Aberystwyth”. Since then I’ve studied programming, pentesting and psychology (the P-subject Triathalon?)… before returning to university to undertake a masters degree in information security and forensics.

Today, I handed in that dissertation. Thanks to digital hand-ins, I’m able to “hand it in” and then change my mind, make changes, and hand-in a replacement version right up until the deadline on Wednesday (I’m already on my second version!), so I’ve still got a few evenings left for last-minute proofreads and tweaks. That said, I’m mostly happy with where it is right now.

Writing a dissertation was harder this time around. Things that made it harder included:

- Writing a masters-level dissertation rather than a bachelors-level one, naturally.

- Opting for a research dissertation rather than an engineering one: I had the choice, and I knew that I’d do better in engineering, but I did research anyway because I thought that the challenge would be good for me.

- Being older! It’s harder to cram information into a late-thirty-something brain than into a young-twenty-something one.

- Work: going through the recruitment process for and starting at Automattic ate a lot of my time, especially as I was used to working part-time at the Bodleian and I’d been turning a little of what would otherwise have been my “freelance work time” into “study time” (last time around I was working part-time for SmartData, of course).

- Life: the kids, our (hopefully) upcoming house move and other commitments are pretty good at getting in the way. Ruth and JTA have been amazing at carving out blocks of time for me to study, especially these last few weekends, which may have made all the difference.

It feels like less of a bang than last time around, but still sufficient that I’ll breathe a big sigh of relief. I’ve a huge backlog of things to get on with that I’ve been putting-off until this monster gets finished, but I’m not thinking about them quite yet.

I need a moment to get my bearings again and get used to the fact that once again – and for the first time in several years – I’ll soon be not-a-student. Fun fact, I’ve spent very-slightly-more than half of my adult life as a registered student: apparently I’m a sucker it, for all that I complain… in fact, I’m already wondering what I can study next (suggestions welcome!), although I’ve promised myself that I’ll take a couple of years off before I get into anything serious.

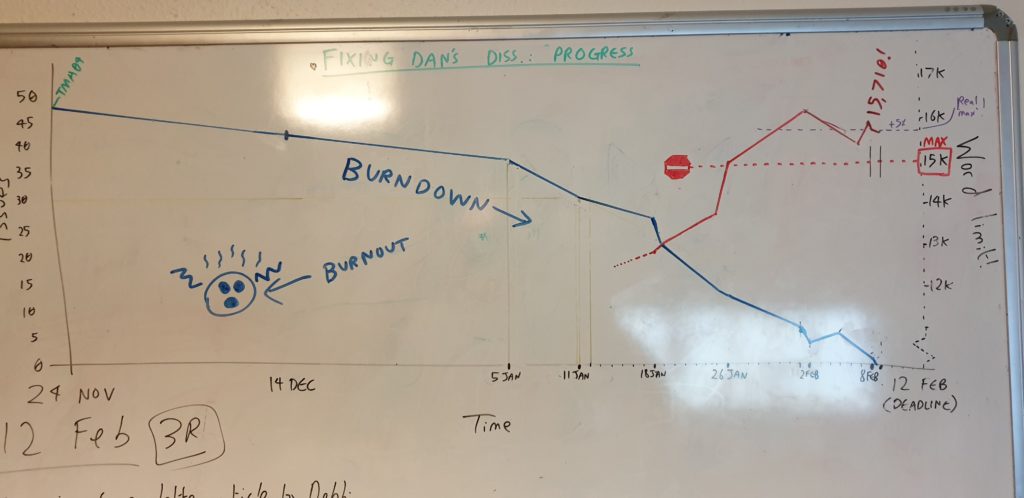

(This is, of course, assuming I pass my masters degree, otherwise I might still be a student for a little longer while I “fix” my dissertation!)

If anybody’s curious (and I shan’t blame you if you’re not), here’s my abstract… assuming I don’t go back and change it yet again in the next couple of days (it’s still a little clunky especially in the final sentence):

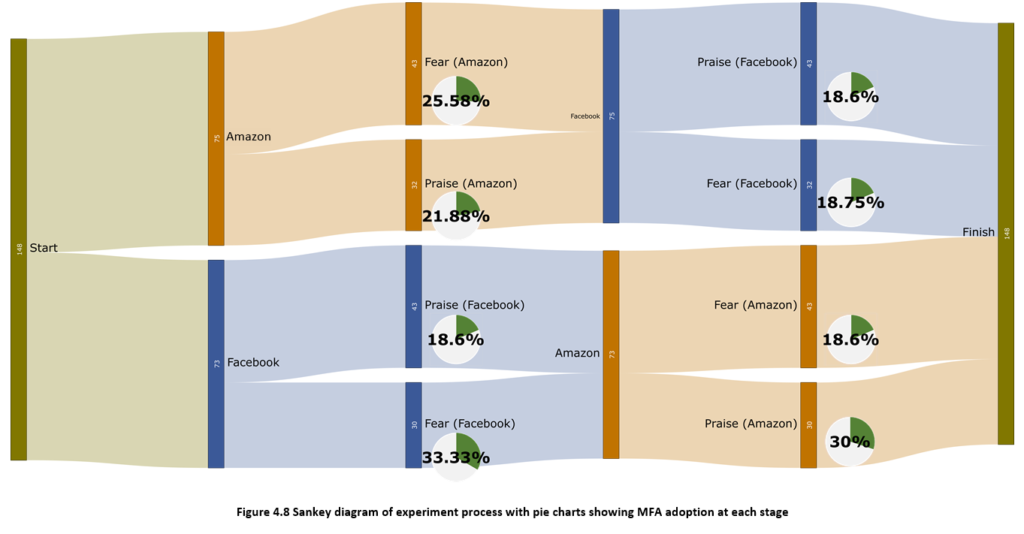

Multifactor authentication (MFA), such as the use of a mobile phone in addition to a username and password when logging in to a website, is one of the strongest security enhancements an individual can add to their online accounts. Compared to alternative enhancements like refraining from the reuse of passwords it’s been shown to be easy and effective. However: MFA is optional for most consumer-facing Web services supporting MFA, and elective user adoption is well under 10%.

How can user adoption be increased? Delivering security awareness training to users has been shown to help, but the gold standard would be a mechanism to encourage uptake that can be delivered at the point at which the user first creates an account on a system. This would provide strong protection to an account for its entire life.

Using realistic account signup scenarios delivered to participants’ own computers, an experiment was performed into the use of language surrounding the invitation to adopt MFA. During the scenarios, participants were exposed to statements designed to either instil fear of hackers or to praise them for setting up an account and considering MFA. The effect on uptake rates is compared. A follow-up questionnaire asks questions to understand user security behaviours including password and MFA choices and explain their thought processes when considering each.

No significant difference is found between the use of “fear” and “praise” statements. However, secondary information revealed during the experiment and survey provides recommendations for service providers to offer MFA after, rather than at, the point of account signup, and for security educators to focus their energies on dispelling user preconceptions about the convenience, privacy implications, and necessity of MFA.