The Community Solar System

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Dan Q

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Science, philosophy and technology run on the model of American Idol – as embodied by TED talks – is a recipe for civilisational disaster.

In our culture, talking about the future is sometimes a polite way of saying things about the present that would otherwise be rude or risky.

But have you ever wondered why so little of the future promised in TED talks actually happens? So much potential and enthusiasm, and so little actual change. Are the ideas wrong? Or is the idea about what ideas can do all by themselves wrong?

I write about entanglements of technology and culture, how technologies enable the making of certain worlds, and at the same time how culture structures how those technologies will evolve, this way or that. It’s where philosophy and design intersect.

…

While you’re tucking in to your turkey tomorrow and the jokes and puzzles in your crackers are failing to impress, here’s a little riddle to share with your dinner guests:

Which is the odd-one out: gypsies, turkeys, french fries, or the Kings of Leon?

In order to save you from “accidentally” reading too far and spoling the answer for yourself, here’s a picture of a kitten to act as filler:

Want a hint? This is a question about geography. Specifically, it’s a question about assumptions about geography. Have another think: the kittens will wait.

Okay. Let’s have a look at each of the candidates, shall we? And learn a little history as we go along:

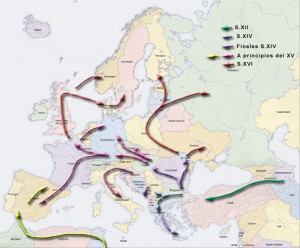

The Romami are an ethnic group of traditionally-nomadic people, originating from Northern India and dispersing across Europe (and further) over the last millenium and a half. They brought with them some interesting anthropological artefacts of their culture, such as aspects of the Indian caste system and languages (it’s through linguistic similarities that we’ve been best-able to trace their multi-generational travels, as written records of their movements are scarce and incomplete), coupled with traditions related to a nomadic life. These traditions include strict rules about hygiene, designed to keep a travelling population free of disease, which helped to keep them safe during the European plagues of the 13th and 14th centuries.

Unfortunately for them, when the native populations of Western European countries saw that these travellers – who already had a reputation as outsiders – seemed to be immune to the diseases that were afflicting the rest of the population, their status in society rapidly degraded, and they were considered to be witches or devil-worshippers. This animosity made people unwilling to trade with them, which forced many of them into criminal activity, which only served to isolate them further. Eventually, here in the UK, laws were passed to attempt to deport them, and these laws help us to see the origins of the term gypsy, which by then had become commonplace.

Consider, for example, the Egyptians Act 1530, which uses the word “Egyptian” to describe these people. The Middle English word for Egypian was gypcian, from which the word gypsy or gipsy was a contraction. The word “gypsy” comes from a mistaken belief by 16th Century Western Europeans that the Romani who were entering their countries had emigrated from Egypt. We’ll get back to that.

When Europeans began to colonise the Americas, from the 15th Century onwards, they discovered an array of new plants and animals previously unseen by European eyes, and this ultimately lead to a dramatic diversification of the diets of Europeans back home. Green beans, cocoa beans, maize (sweetcorn), chillis, marrows, pumpkins, potatoes, tomatoes, buffalo, jaguars, and vanilla pods: things that are so well-understood in Britain now that it’s hard to imagine that there was a time that they were completely alien here.

Still thinking that the Americas could be a part of East Asia, the explorers and colonists didn’t recognise turkeys as being a distinct species, and categorised them as being a kind of guineafowl. They soon realised that they made for pretty good eating, and started sending them back to their home countries. Many of the turkeys sent back to Central Europe arrived via Turkey, and so English-speaking countries started calling them Turkey fowl, eventually just shortened to turkey. In actual fact, most of the turkeys reaching Britain probably came directly to Britain, or possibly via France, Portugal, or Spain, and so the name “turkey” is completely ridiculous.

Fun fact: in Turkey, turkeys are called hindi, which means Indian, because many of the traders importing turkeys were Indians (the French, Polish, Russians, and Ukranians also use words that imply an Indian origin). In Hindi, they’re called peru, after the region and later country of Peru, which also isn’t where they’re from (they’re native only to North America), but the Portugese – who helped to colonise Peru also call them that. And in Scottish Gaelic, they’re called cearc frangach – “French chicken”! The turkey is a seriously georgraphically-confused bird.

As I’m sure that everybody knows by now, “French” fries probably originated in either Belgium or in the Spanish Netherlands (now part of Belgium), although some French sources claim an earlier heritage. We don’t know how they were first invented, but the popularly-told tale of Meuse Valley fishing communities making up for not having enough fish by deep-frying pieces of potato, cut into the shape of fish, is almost certainly false: a peasant region would be extremely unlikely to have access to the large quantities of fat required to fry potatoes in this way.

So why do we – with the exception of some confusingly patriotic Americans – call them French fries. It’s hard to say for certain, but based

on when the food became widely-known in the anglophonic world, the most-likely explanation comes from the First World War. When British and, later, American soldier landed in Belgium,

they’ll have had the opportunity to taste these (now culturally-universal) treats for the first time. At that time, though, the official language of the Belgian army (and the

most-popularly spoken language amongst Belgian citizens) was French. The British and American soldiers thus came to call them “French fries”.

For a thousand years the Kingdom of Leon represented a significant part of what would not be considered Spain and/or Portugal, founded by Christian kings who’d recaptured the Northern half of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors during the Reconquista (short version for those whose history lessons didn’t go in this direction: what the crusades were against the Ottomans, the Reconquista was against the Moors). The Kingdom of Leon remained until its power was gradually completely absorbed into that of the Kingdom of Spain. Leon still exists as a historic administrative region in Spain, similar to the counties of the British Isles, and even has its own minority language (the majority language, Spanish, would historically have been known as Castilian – the traditional language of the neighbouring Castillian Kingdom).

The band, however, isn’t from Leon but is from Nashville, Tennessee. They’ve got nothing linking them to actual Leon, or Spain at all, as far as I can tell, except for their name – not unlike gypsies and Egypt, turkeys and Turkey, and French fries and France. The Kings of Leon, a band of brothers, took the inspiration for their name from the first name of their father and their grandfather: Leon.

The Kings of Leon are the odd one out, because while all four have names which imply that they’re from somewhere that they’re not, the inventors of the name “The Kings of Leon” were the only ones who knew that the implication was correct.

The people who first started calling gypsies “gypsies” genuinely believed that they came from Egypt. The first person to call a turkey a “Turkey fowl” really was under the impression that it was a bird that had come from, or via, Turkey. And whoever first started spreading the word about the tasty Belgian food they’d discovered while serving overseas really thought that they were a French invention. But the Kings of Leon always knew that they weren’t from Leon (and, presumably, that they weren’t kings).

And as for you? Your sex is on fire. Well, either that or it’s your turkey. You oughta go get it out of the oven if it’s the latter, or – if it’s the former – see if you can get some cream for that. And have a Merry Christmas.

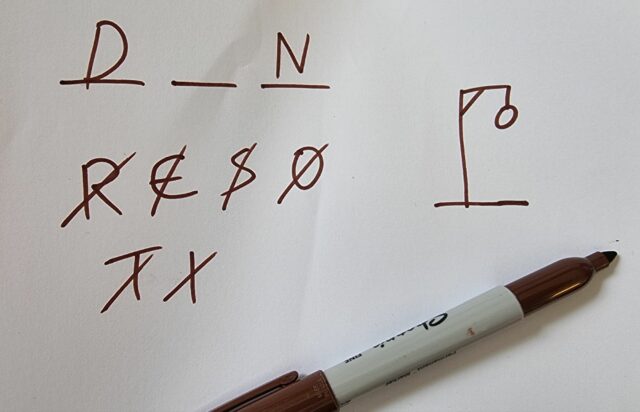

What’s the hardest word to guess, when playing hangman? I’ll come back to that.

Last year, Nick Berry wrote a fantastic blog post about the optimal strategy for Hangman. He showed that the best guesses to make to get your first “hit” in a game of hangman are not the most-commonly occurring letters in written English, because these aren’t the most commonly-occurring letters in individual words. He also showed that the first guesses should be adjusted based on the length of the word (the most common letter in 5-letter words is ‘S’, but the most common letter in 6-letter words is ‘E’). In short: hangman’s a more-complex game than you probably thought it was! I’d like to take his work a step further, and work out which word is the hardest word: that is – assuming you’re playing an optimal strategy, what word takes the most-guesses?

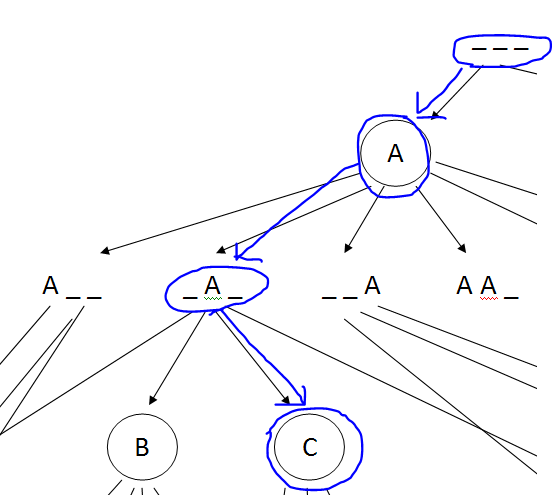

First, though, we need to understand how hangman is perfectly played. Based on the assumption that the “executioner” player is choosing words randomly, and that no clue is given as to the nature of the word, we can determine the best possible move for all possible states of the game by using a data structure known as a tree. Suppose our opponent has chosen a three-letter word, and has drawn three dashes to indicate this. We know from Nick’s article that the best letter to guess is A. And then, if our guess is wrong, the next best letter to guess is E. But what if our first guess is right? Well, then we’ve got an “A” in one or more positions on the board, and we need to work out the next best move: it’s unlikely to be “E” – very few three-letter words have both an “A” and an “E” – and of course what letter we should guess next depends entirely on what positions the letters are in.

What we’re actually doing here is a filtering exercise: of all of the possible letters we could choose, we’re considering what possible results that could have. Then for each of those results, we’re considering what guesses we could make next, and so on. At each stage, we compare all of the possible moves to a dictionary of all possible words, and filter out all of the words it can’t be: after our first guess in the diagram above, if we guess “A” and the board now shows “_ A _”, then we know that of the 600+ three-letter words in the English language, we’re dealing with one of only about 134. We further refine our guess by playing the odds: of those words, more of them have a “C” in than any other letter, so that’s our second guess. If it has a C in, that limits the options further, and we can plan the next guess accordingly. If it doesn’t have a C in, that still provides us with valuable information: we’re now looking for a three-letter word with an A in the second position and no letter C: that cuts it down to 124 words (and our next guess should be ‘T’). This tree-based mechanism for working out the best moves is comparable to that used by other game-playing computers. Hangman is simple enough that it can be “solved” by contemporary computers (like draughts – solved in 2007 – but unlike chess: while modern chess-playing computers can beat humans, it’s still theoretically possible to build future computers that will beat today’s computers).

Now that we can simulate the way that a perfect player would play against a truly-random executioner, we can use this to simulate games of hangman for every possible word (I’m using version 0.7 of this British-English dictionary). In other words, we set up two computer players: the first chooses a word from the dictionary, the second plays “perfectly” to try to guess the word, and we record how many guesses it took. So that’s what I did. Here’s the Ruby code I used. It’s heavily-commented and probably pretty understandable/good learning material, if you’re into that kind of thing. Or if you fancy optimising it, there’s plenty of scope for that too (I knocked it out on a lunch break; don’t expect too much!). Or you could use it as the basis to make a playable hangman game. Go wild.

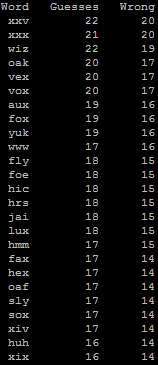

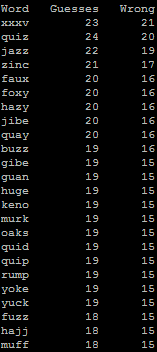

Running the program, we can see that the hardest three-letter word is “xxv”, which would take 22 guesses (20 of them wrong!) to get. But aside from the roman numeral for 25, I don’t think that “xxv” is actually a word. Perhaps my dictionary’s not very good. “Oak”, though, is definitely a word, and at 20 guesses (17 wrong), it’s easily enough to hang your opponent no matter how many strokes it takes to complete the gallows.

There are more tougher words in the four-letter set, like the devious “quiz”, “jazz”, “zinc”, and “faux”. Pick one of those and your opponent – unless they’ve seen this blog post! – is incredibly unlikely to guess it before they’re swinging from a rope.

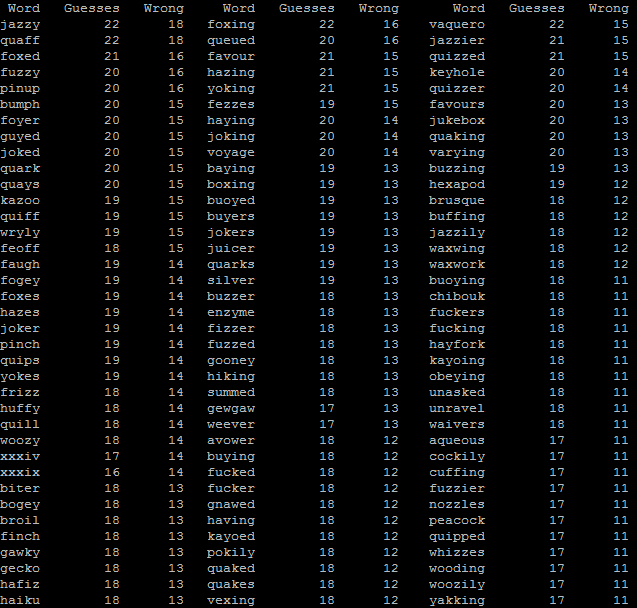

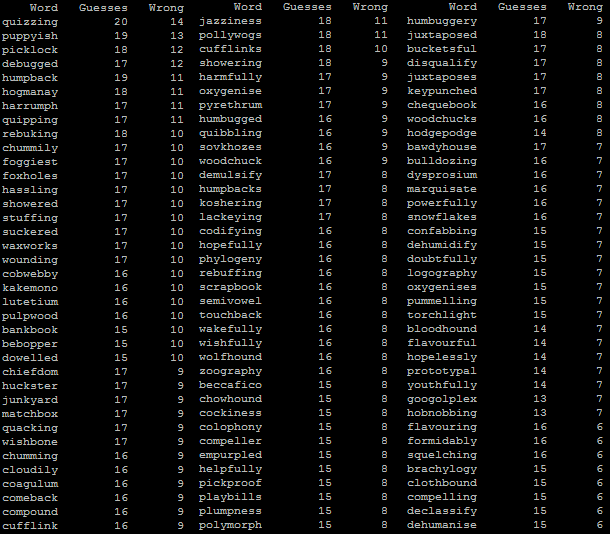

As we get into the 5, 6, and 7-letter words you’ll begin to notice a pattern: that the hardest words with any given number of letters get easier the longer they are. That’s kind of what you’d expect, I suppose: if there were a hypothetical word that contained every letter in the alphabet, then nobody would ever fail to (eventually) get it.

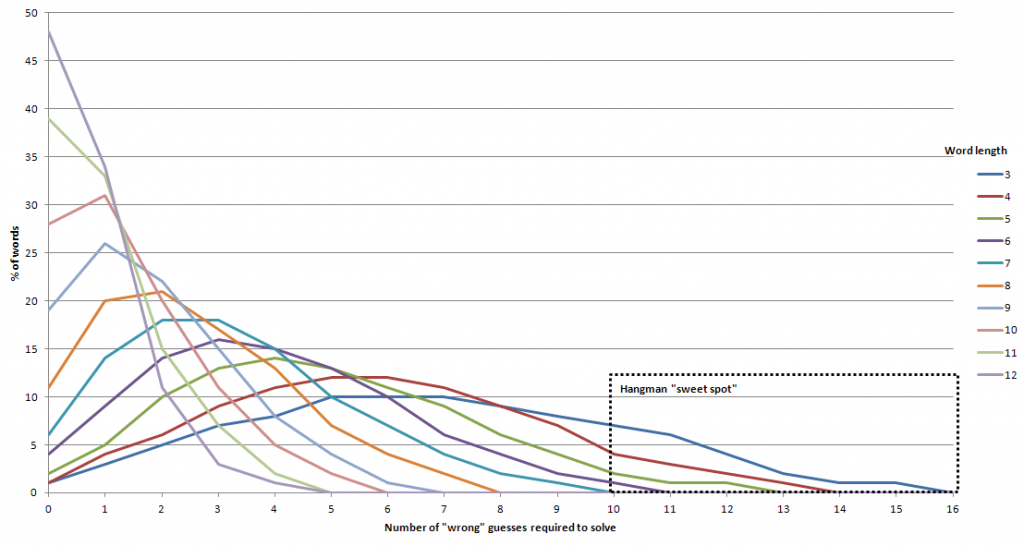

When we make a graph of each word length, showing which proportion of the words require a given number of “wrong” guesses (by an optimised player), we discover a “sweet spot” window in which we’ll find all of the words that an optimised player will always fail to guess (assuming that we permit up to 10 incorrect guesses before they’re disqualified). The window seems small for the number of times I remember seeing people actually lose at hangman, which implies to me that human players consistently play sub-optimally, and do not adequately counteract that failing by applying an equal level of “smart”, intuitive play (knowing one’s opponent and their vocabulary, looking for hints in the way the game is presented, etc.).

In case you’re interested, then, here are the theoretically-hardest words to throw at your hangman opponent. While many of the words there feel like they would quite-rightly be difficult, others feel like they’d be easier than their ranking would imply: this is probably because they contain unusual numbers of vowels or vowels in unusual-but-telling positions, which humans (with their habit, inefficient under normal circumstances, of guessing an extended series of vowels to begin with) might be faster to guess than a computer.

| Word | Guesses taken | “Wrong” guesses needed |

|---|---|---|

| quiz | 24 | 20 |

| jazz | 22 | 19 |

| jazzy | 22 | 18 |

| quaff | 22 | 18 |

| zinc | 21 | 17 |

| oak | 20 | 17 |

| vex | 20 | 17 |

| vox | 20 | 17 |

| foxing | 22 | 16 |

| foxed | 21 | 16 |

| queued | 20 | 16 |

| fuzzy | 20 | 16 |

| quay | 20 | 16 |

| pinup | 20 | 16 |

| fox | 19 | 16 |

| yuk | 19 | 16 |

| vaquero | 22 | 15 |

| jazzier | 21 | 15 |

| quizzed | 21 | 15 |

| hazing | 21 | 15 |

| favour | 21 | 15 |

| yoking | 21 | 15 |

| quays | 20 | 15 |

| quark | 20 | 15 |

| joked | 20 | 15 |

| guyed | 20 | 15 |

| foyer | 20 | 15 |

| bumph | 20 | 15 |

| huge | 19 | 15 |

| quip | 19 | 15 |

| gibe | 19 | 15 |

| rump | 19 | 15 |

| guan | 19 | 15 |

| quizzed | 19 | 15 |

| oaks | 19 | 15 |

| murk | 19 | 15 |

| fezzes | 19 | 15 |

| yuck | 19 | 15 |

| keno | 19 | 15 |

| kazoo | 19 | 15 |

|

Download a longer list

(there’s plenty more which you’d expect to “win” with) |

||

If you use this to give you an edge in your next game, let me know how it works out for you!

Update – 8 March 2019: fixed a broken link and improved the layout of the page.

I’ve had a tardy summer for blogging, falling way behind on many of the things I’d planned to write about. Perhaps the problem is that I’m still on Narrowboat Time, the timezone of a strange parallel universe in which everything happens more-slowly, in a gin-soaked, gently-rocking, slowly-crawling haze.

That’s believable, because this summer Ruth, JTA and I – joined for some of the journey by Matt – rented a narrowboat and spent a week drifting unhurriedly down the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal… and then another week making a leisurely cruise back up it again.

We picked up Nerys, out of Cambrian Cruisers, who also gave us an introduction to the operation of the boat (driving it, filling it with water, pumping out sewage, generating electricity for appliances, etc.) and safety instructions (virtually all of the canal is less than four feet deep, so if you fall in, the best thing to do is to simply walk to the shore), and set out towards Brecon. In order to explore the entire canal in the time available, we needed to cover an average of only five miles per day. When you’re going at about two and a half miles per hour and having to stop to operate locks (there are only six locks on the navigable stretch of the canal, but they’re all clustered towards the upper end), though, five miles is plenty.

The upper end of the canal is by far the busiest, with not only narrowboats cruising up and down but a significant number of day boats (mostly on loan from Brecon) and at least one tour boat: a 50-seater that you don’t want to have to wiggle past at sharp corner North of the Bryich Aqueduct. From a navigation perspective, though, it’s also the best-maintained: wide enough that two boats can pass one another without much thought, and deep enough across its entire width that you needn’t be concerned about running aground, it makes for a great starting point for people who want some narrowboating practice before they hit the more challenging bits to the South.

Ruth was excited to find in me a driver who was confident holding the boat steady in a lock. Perhaps an expression of equal parts talent and arrogance, I was more than happy to take over the driving, leaving others to jump out and juggle the lock gates and lift bridges. Owing to Ruth’s delicate condition, we’d forbidden her from operating the entirely-manual locks, but she made sure to get a go at running one of the fancy hydraulic ones.

After each day’s cruising, we’d find a nice place to moor up, open a bottle of wine or mix up some gin-and-tonics, and lounge in the warm, late summer air.

As we wound our way further South, to the “other” end of the waterway, we discovered that the already-narrow canal was ill-dredged, and drifting anywhere close to the sides – especially on corners – was a recipe for running around. Crewmates who weren’t driving would take turns on “pole duty”, being on standby to push us off if we got too close to one or the other bank.

Each night moored up in a separate place gives a deceptive feeling of travel. Deceptive, because I’ve had hiking trips where I’ve traveled further each day than we did on our boat! But the nature of the canal, winding its way from the urban centre of Brecon out through the old mining villages of South Wales.

The canal, already quite narrow and shallow, only became harder to navigate as we got further South. Our weed hatch (that’s the door to the propeller box, that is, not a slang term for the secret compartment where you keep your drugs) saw plenty of use, and we found ourselves disentangling all manner of curious flora in order to keep our engine pushing us forwards (and not catching fire).

Eventually, we had to give up navigating the waterway, tie up, and finish the journey on foot. We could have gotten the boat all the way to the end, but it’d have been a stop-start day of pushing ourselves off the shallow banks and cleaning out the weed hatch. Walking the last few miles – with a stop either way at a wonderful little pub called The Open Hearth – let us get all the way to both ends of the navigable stretch of the canal, with a lot less hassle and grime.

It’s a little sad coming to the end of a waterway, cut short – in this case – by a road. There’s no easy way – short of the removal of an important road, or the challenging and expensive installation of a drop lock, that this waterway will ever be connected at this point again. The surrounding landscape doesn’t even make it look likely that it’ll be connected again by a different route, either: this canal is broken here.

I found myself remarking on quite how well-laid-out the inside of the narrowboat was. Naturally, on a vehicle/home that’s so long and thin, a great number of clever decisions had clearly been made. The main living space could be converted between a living room, dining room, and bedroom by re-arranging planks and poles; the kitchen made use of carefully-engineered cupboards to hold the crockery in place in case of a… bump; and little space-saving features added up all along the boat, such as the central bedroom’s wardrobe door being adaptable to function as a privacy door between the two main bedrooms.

On the way back up the canal, we watched the new boaters setting out in their narrowboats for the first time. We felt like pros, by now, gliding around the corners with ease and passing other vessels with narry a hint of a bump. We were a well-oiled machine, handling every lock with ease. Well: some ease. Unfortunately, we’d managed to lose not one but both of our windlasses on the way down the canal and had to buy a replacement pair on the way back up, which somewhat dented our “what pros we are” feeling.

Coming to the end of our narrowboating journey, we took a quick trip to Fourteen Locks, a beautiful and series of locks with a sophisticated basin network, disconnected from the remains of the South Wales canal network. They’ve got a particular lock (lock 11), there, whose unusual shape hints at a function that’s no-longer understood, which I think it quite fabulously wonderful – that we could as a nation built a machine just 200 years ago, used it for a hundred years, and now have no idea how it worked.

Our next stop was Ikea, where we’d only meant to buy a couple of shelves for our new home, but you know how it is when you go to Ikea.

We wrapped up our holiday with a visit to Sian and Andy (and their little one), and Andy showed off his talent of singing songs that send babies to sleep. I swear, if he makes an album of children’s songs and they’re as effective as he is in person, we’ll buy a copy.

Altogether, a wonderfully laid-back holiday that clearly knocked my sense of urgency so far off that I didn’t blog about it for several months.

Edit, 22 June 2018: after somebody from the Canal & River Trust noticed that my link to their page on the Brynich Aqueduct was broken after they’d rearranged their site, I removed it. They suggested an alternative page, but it didn’t really have the same content (about the aqueduct itself) so I’ve just removed the link. Boo, Canal & River Trust! Cool URIs Don’t Change!

This link was originally posted to /r/MegaMegaLounge. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

The original link was: http://us.123rf.com/400wm/400/400/scanrail/scanrail1201/scanrail120100065/12033124-set-of-gold-bars-isolated-on-white-background.jpg

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Golomb Rulers and Costas Arrays.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

GoldieBlox have been in the news (by which I mean the blogs) a lot lately because of their Princess Machine video. In case you missed the memo, GoldieBlox do engineering toys for girls, by which they mean a) they’re pink, and b) they’ve got stories, because girls need everything to have a story. Think I’m…

Unused footage from Godzilla Huntley’s Family Vlog covers the debate between Godzilla and her mother about whether or not Falcor, the luck dragon from The Neverending Story, is a mammal.

The argument remains unresolved.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

How to create perfect secret messages that can be decoded using just your eyes.

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

A few months ago now (OK, this post has sat in drafts for a while) when I came to pick my daughter up from nursery I found her wearing a pink ‘fairy skirt’ (something like a tutu). “Her trousers and her spare trousers both got wet and it was the only thing we could find!”…

This self-post was originally posted to /r/SuicideWatch. See more things from Dan's Reddit account.

Posted 3 hours ago; sounds like they could do with some help:

I don’t know what to do anymore. I’ve exhausted any little hope I’d had, and now there’s nothing.

I just want it to be over. By any means necessary.

http://www.reddit.com/r/self/comments/1qw4tm/i_feel_like_everything_i_do_is_inherently_stupid/

This is not a blog post about pentesting, or any other kind of software-engineering inspired testing of pens. Nor is it a blog post about the kind of fascination some people have with pens and ink. Instead, this is a blog post about history and psychology.

Recently, JTA asked me what I do when I want to test a pen, and he was surprised with the answer. Before I tell you how I answered, I’ll tell you about what I learned from the conversation. And before that, I’ll tell you about the history of pen testing. And then, finally, I’ll tell you why I think it’s important from a psychological perspective.

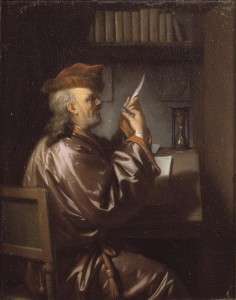

Historically, the “breaking in” of a new pen was called a probatio pennae, literally “pen test”, and would typically be a few lines of text or a short proverb: something that demonstrated the pen’s ability to write. For the entire mediaeval period, plus several centuries besides, the principle instrument for writing would be the quill pen: the primary wing feathers of a large bird such as a goose, often hardened in hot ashes, stripped of barbs, and cut down to size with an blade whose purpose lends its name to what we now call a “pen knife”. With such a tool, a scribe would want to be sure that the pen could hold an adequate nibful of ink without splashing or spraying, and – despite the high value of paper – it was clearly essential to write a whole sentence or two to be sure.

A modern ballpoint pen has no such issues, but instead introduces some of its own: a plastic-lined inkwell can be gradually penetrated by the air, causing the ink to dry up; the ball can become stuck and will not turn freely; air bubble can develop within the tube (especially if the pen is stored, or worse-still used, the wrong way up); and, of course, the pen can run out of ink. This typically precipitates its disposal: your biro isn’t built to be re-used for anything except perhaps to perform an emergency tracheotomy, and it’s cheap enough that you don’t want to waste your time repairing it. As a result, our pen tests have become fast, designed to determine within a few seconds whether the pen we’ve got is working or, in the case of a stuck ball, can be made to start working with a sufficiency of scribbling. Our culture of disposal can’t spare the time for any more than a cursory test before we give up and grab the next one.

So what do we write? What is the probatio pennae of our times? It’s been widely-reported (although I can’t find any decent citations) that, upon being offered a new pen to try out, 97% of people will write their own name. Now that statistic smells fishy to me (no good citations anywhere, and 97% of people use 97% as their “virtually all” number, for made-up statistics), but I’ve been testing the hypothesis among friends these last few days, and I’ve gathered enough evidence to convince me that it’s probably the case that many or most people will write their own name to test a pen.

Somebody had presumably asked JTA what he wrote, earlier in the day, because he took the time to tell me that when he tests a new pen, he typically writes the word “hello”.

Now I find that pretty weird. Maybe it’s the software engineer in me, but to me the mark of a good test is that it covers all of the possible cases, in the minimal possible effort. Writing your name is easy because it’s managed by what is popularly-called “muscle memory”: a second-season episode of Castle (correctly) used this as a plot point, when a man suffering from retrograde amnesia was unable to remember his name, but was still able to sign his name because the act of signing it had been rendered, by years of practice, into his procedural memory, which was unaffected by his condition. But writing a word, like “hello”… requires a comprehension of language. Unless he’s tested enough pens to have built a procedural memory of writing “hello” to test pens, JTA’s test has a greater number of neural dependencies, which – with apologies to those of you who aren’t interested in automated software testing – produces what we’d call an unnecessarily “brittle” test.

Me? I just scribble, which my quick survey (and several comparable ones online) show to be probably the second-most popular action to test a pen. Scribbling, to me, simply seems like the minimal test path: the single simplest thing that can be done with a pen that will demonstrate that it’s fit for purpose. I don’t need to test that a new pen can write words, because – to me – writing words in particular is not a function of the pen, but a function of my brain! To me, the pen’s function is simply one of transferring ink to the paper, and any semantic meaning coming from the ink is a product of my intellect, not of the writing implement.

So why is this important? Well: I have a half-baked hypothesis that the choice of what to write with a new pen might be linked to other aspects of our psychology. When I’m developing a new template for a website, for example, I use lorem ipsum text and dummy placeholder images as filler (just occasionally, I’ll use kittens, because kittens are adorable). That’s because the absence of meaning to the words that appear (I don’t read Latin, and even if I did, lorem ipsum is frequently mangled) has no bearing on my comprehension of the design: and, in fact, it can sometimes be a benefit to be deprived of the distraction of legible content.

But I’d hypothesise that people who write words as a probatio pennae would be less-comfortable with illegible placeholder-text in a design than those who drew scribbles or signed their name. I have a notion, from my own experience, that the same parts of the brain that is responsible for judging the quality of a writing implement are used in the judgement of a piece of design work. Hey: maybe if that’s true, graphic designers should have their clients test pens out, in their presence, before they decide whether to use believable filler or lorem ipsum text in the designs they’d like approved.

Or maybe I’m way off base. What do you write when you test a pen?

This is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Disclaimer: I do not build database engines. I build web applications. I run 4-6 different projects every year, so I build a lot of web applications. I see apps with different requirements and different data storage needs. I’ve deployed most of the data stores you’ve heard about, and a few that you probably haven’t. I’ve picked the wrong…

The story of how the Diaspora social network adopted the hip new database technology without for a moment thinking about whether it was the right database technology.