Last week I was talking to Alexander Dutton about an idea that we had to implement cookie-like behaviour using browser caching. As I first mentioned last year, new laws are coming into force across Europe that will require websites to ask for your consent before they store cookies on your computer. Regardless of their necessity, these laws are badly-defined and ill thought-out, and there’s been a significant lack of information to support web managers in understanding and implementing the required changes.

To illustrate one of the ambiguities in the law, I’ve implemented a tool which tracks site visitors almost as effectively as cookies (or similar technologies such as Flash Objects or Local Storage), but which must necessarily fall into one of the larger grey areas. My tool abuses the way that “permanent” (301) HTTP redirects are cached by web browsers.

[callout][button link=”http://c301.scatmania.org/” align=”right” size=”medium” color=”green”]See Demo Site[/button]You can try out my implementation for yourself. Click on the button to see the sample site, then close down all of your browser windows (or even restart your computer) and come back and try again: the site will recognise you and show you the same random number as it did the first time around, as well as identifying when your first visit was.[/callout]

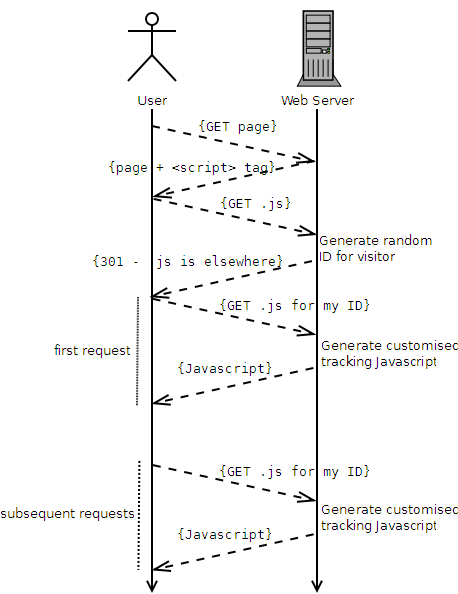

Here’s how it works, in brief:

- A user visits the website.

- The website contains a <script> tag, pointing at a URL where the user’s browser will find some Javascript.

- The user’s browser requests the Javascript file.

- The server generates a random unique identifier for this user.

- The server uses a HTTP 301 response to tell the browser “this Javascript can be found at a different web address,” and provides an address that contains the new unique identifier.

- The user’s browser requests the new document (e.g. /javascripts/tracking/123456789.js, if the user’s unique ID was 123456789).

- The resulting Javascript is generated dynamically to automatically contain the ID in a variable, which can then be used for tracking purposes.

- Subsequent requests to the server, even after closing the browser, skip steps 3 through 5, because the user’s browser will cache the 301 and re-use the unique web address associated with that individual user.

Compared to conventional cookie-based tracking (e.g. Google Analytics), this approach:

- Is more-fragile (clearing the cache is a more-common user operation than clearing cookies, and a “force refresh” may, in some browsers, result in a new tracking ID being issued).

- Is less-blockable using contemporary privacy tools, including the W3C’s proposed one: it won’t be spotted by any cookie-cleaners or privacy filters that I’m aware of: it won’t penetrate incognito mode or other browser “privacy modes”, though.

Moreover, this technique falls into a slight legal grey area. It would certainly be against the spirit of the law to use this technique for tracking purposes (although it would be trivial to implement even an advanced solution which “proxied” requests, using a database to associate conventional cookies with unique IDs, through to Google Analytics or a similar solution). However, it’s hard to legislate against the use of HTTP 301s, which are an even more-fundamental and required part of the web than cookies are. Also, and for the same reasons, it’s significantly harder to detect and block this technique than it is conventional tracking cookies. However, the technique is somewhat brittle and it would be necessary to put up with a reduced “cookie lifespan” if you used it for real.

[callout][button link=”http://c301.scatmania.org/” align=”right” size=”medium” color=”green”]See Demo Site[/button] [button link=”https://gist.github.com/avapoet/5318224″ align=”right” size=”medium” color=”orange”]Download Code[/button] Please try out the demo, or download the source code (Ruby/Sinatra) and see for yourself how this technique works.[/callout]

Note that I am not a lawyer, so I can’t make a statement about the legality (or not) of this approach to tracking. I would suspect that if you were somehow caught doing it without the consent of your users, you’d be just as guilty as if you used a conventional approach. However, it’s certainly a technically-interesting approach that might have applications in areas of legitimate tracking, too.

Update: The demo site is down, but I’ve update the download code link so that it still works.