I’ve always been enamoured with the concept of urban exploration: that is, the infiltration and examination of abandoned human structures. I was reminded of this recently, when Ruth, JTA and I got the chance to go on an (organised) tour of long-abandoned Aldwych Tube Station in London.

I think for me the appeal comes from the same place as it does when I’m looking around, for example, the ruin of a castle or the wreck of a ship. As opposed to the exploration of the natural world, looking around a man-made thing really gives you the feeling that you’re uncovering the long-lost purpose of the place. This place you are was designed and built to fill a particular need and, for whatever reason, it’s now left to rot and decay. And you – the amateur urban archaeologist, are the link that connects this abandoned world with the present.

I’ve been thinking about some of the places I’ve explored – sewer tunnels underneath what is now Deepdale Retail Park, waterlogged WWII bunkers occupied by squatters, disused railway lines and railyards, roofs of semi-accessible castles, and the (then-disused) wreck that was Aberystwyth’s Alexandra Hall, back when tragically-empty buildings was part of the quirky charm of the place, before they transformed into being a symptom of its downfall. I wanted to share with you a story or two. But instead of any of these, I’ve picked a place that none of you are likely to have heard about:

Wittingham Hospital

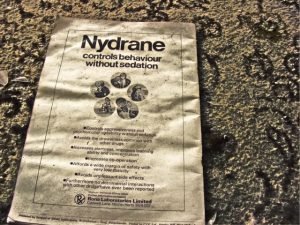

In the mid-19th century, the lunatic asylums of Lancashire and Merseyside were overflowing, and Wittingham Mental Hospital was built to replace them. Originally built to hold 1000 patients, it held over 3,500 by the outbreak of the second world war, making it the largest mental hospital in the country. The mental health reforms of the 1960s (and an inquiry into patient abuse), and new drugs and treatments in the 1970s and 1980s, led to it being gradually emptied and, in 1995, closing for good.

I was still at school when word got around about the closure and a couple of friends and I decided to cycle up to the old hospital and explore it, because there’s nothing like schoolboys egging one another on to give you the courage to “break into the old asylum”. Apparently when I was a kid, I didn’t watch enough horror films about haunted old buildings or about murderous psychopaths, because it seemed like a perfectly reasonable suggestion to me. The council have since put up secure fences and begun demolition, but back then it didn’t take more than a little bit of climbing to gain access to the abandoned complex.

There was a deathly quiet inside the buildings. The distance from the nearest road and the surrounding woodlands muffled the distant sounds of the outside world to less than a whisper, and as the three of us split up and spread out, it was very easy to feel completely alone. The silence was more comforting, though, than eerie: on the hard tile floors and in the big, empty rooms, it’d be impossible to catch anybody unawares, no matter how fleet of foot you might be.

I was surprised to see quite how much furniture and equipment had been simply left: it was almost as if the buildings had been evacuated in a panic, rather than undergoing a controlled, phased closure. Filing cabinets remained, stuffed with papers, in a room with net curtains and a carpet. An upright piano, only slightly out-of-tune, remained in an otherwise empty ward. Beds, operating tables, and cupboards stood exactly as they had when the hospital was still alive.

I couldn’t understand how a place could be abandoned in this way. It’s as if the place itself had died and, instead of being buried, had just been left to decompose in the open air. It seemed – at the least – irresponsible: a friend of mine even came across surgical supplies and syringes, simply left in a cupboard… but more than that, it seemed disrespectful to the building to leave it responsible for looking after these memories of its old self: things which no longer have any purpose, of which it was the custodian, unwilling and unthanked.

We didn’t take any photos – I’m not sure that any of us owned a camera, back then – and we didn’t liberate any of the paperwork (tempting though it was). I’m pretty sure that not one of the three felt that our parents would have approved of us illicitly gaining access to a disused medical facility, so any evidence of our presence was to be avoided! But there was more than that at stake: spending an hour or two wandering around these forgotten corridors, I felt more like a ghost than like a person. We crept about in silence, not saying a word to one another until we’d all reached perimeter once more. It wasn’t our place to interact with this building: all we were there to do was to observe, impotently: to see the beginning of its long decay, that’s since been documented by so many others. That was enough.

I’ll tell you what, though: that early experience? I totally hold it responsible for my subsequent interest in abandoned places.