This post is part of my attempt at Bloganuary 2024. Today’s prompt is:

What are your thoughts on the concept of living a very long life?

Today’s my 43rd birthday. Based on the current best statistics available for my age and country, I might expect to live about the same amount of time again: I’m literally about half-way through my anticipated life, today.1

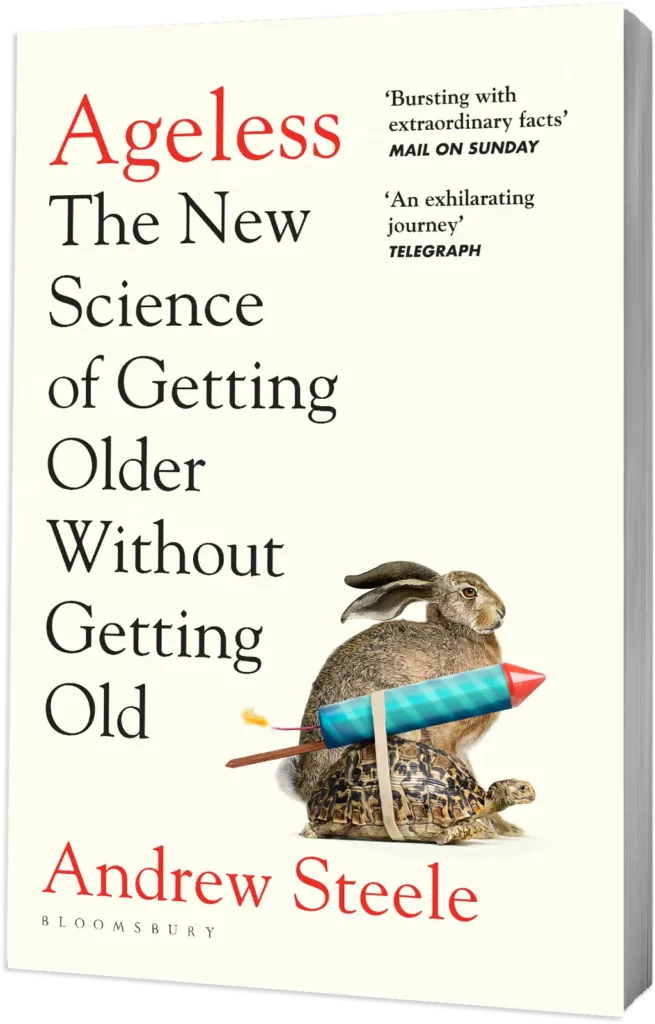

Naturally, that’s the kind of shocking revelation that can make a person wish for an extended lifespan. Especially if, y’know, you read Andrew’s book on the subject and figured that, excitingly, we’re on the cusp of some meaningful life extension technologies!

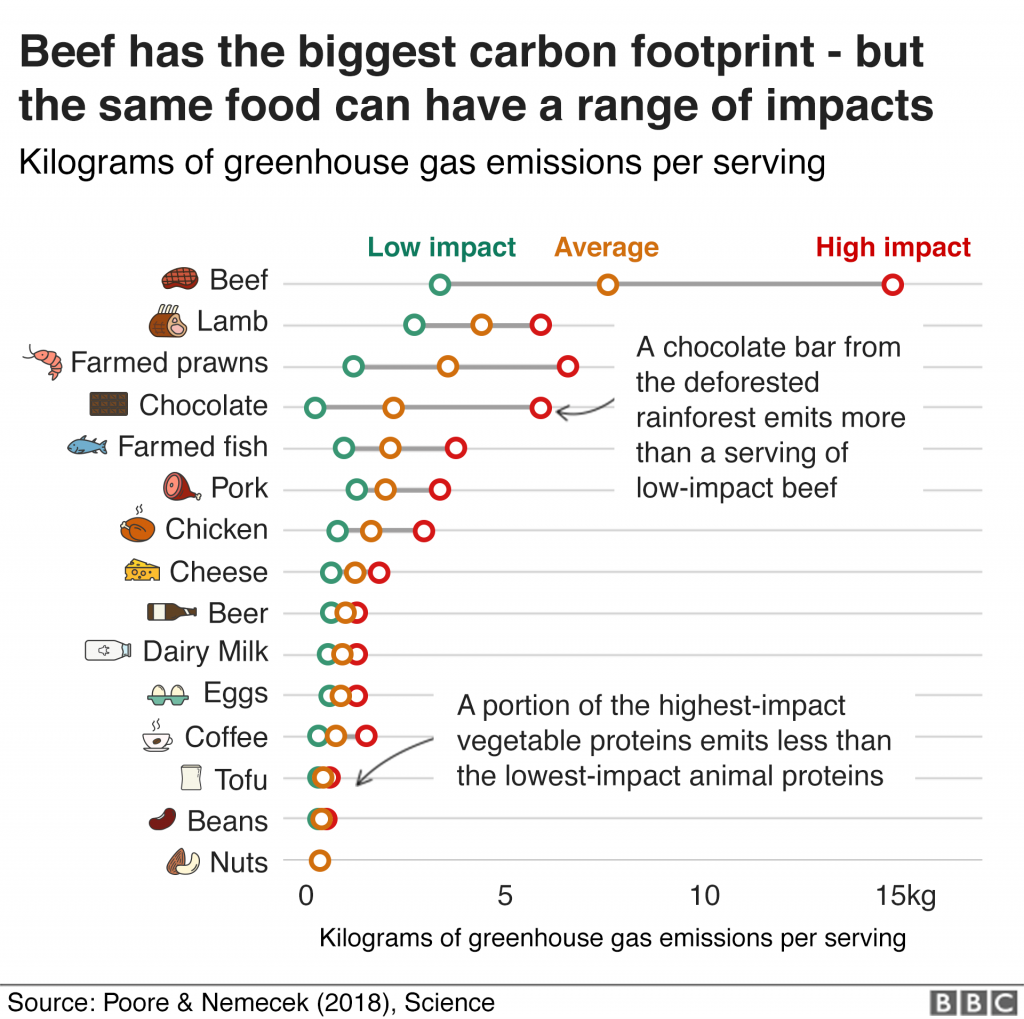

My very first thought when I read Andrew’s thoughts on lifespan extension was exactly the kind of knee-jerk panic response he tries to assuage with his free bonus chapter. He spends a while explaining how he’s not just talking about expending lifespan but healthspan, and so the need healthcare resources that are used to treat those in old-age wouldn’t increase dramatically as a result of lifespan increase, but that’s not the bit that worries me. My concern is that lifespan extension technologies will be unevenly distributed, and the (richer) societies that get them first are those same societies whose (richer) lifestyle has the greater negative impact on the Earth’s capacity to support human life.2

Andrew anticipates this concern and does some back-of-napkin maths to suggest that the increase in population doesn’t make too big an impact:

In this ‘worst’ case, the population in 2050 would be 11.3 billion—16% larger than had we not defeated ageing.

Is that a lot? I don’t think so—I’d happily work 16% harder to solve environmental problems if it meant no more suffering from old age.

This seems to me to be overly-optimistic:

- The Earth doesn’t care whether or not you’re happy to work 16% harder to solve environmental problems if that extra effort isn’t possible (there’s necessarily an upper limit to how much change we can actually effect).

- 16% extra population = 16% extra “work” to save them implies a linear relationship between the two that simply doesn’t exist.

- And that you’re willing to give 16% more doesn’t matter a jot if most of the richest people on the planet don’t share that ideal.

Fortunately, I’m reassured by the fact that – as Andrew points out – change is unlikely to happen fast. That means that the existing existential threat of climate change remains a bigger and more-significant issue than potential future overpopulation does!

In short: while I’m hoping I’ll live happily and healthily to say 120, I don’t think I’m ready for the rest of the world to all suddenly start doing so too! But I think there are bigger worries in the meantime. I don’t fancy my chances of living long enough to find out.

Gosh, that’s a gloomy note for a birthday, isn’t it? I’d better get up and go do something cheerier to mark the day!

Footnotes

1 Assuming I don’t die of something before them, of course. Falling off a cliff isn’t a heritable condition, is it? ‘Cos there’s a family history of it, and I’ve always found myself affected by the influence of gravity, which I believe might be a precursor to falling off things.

2 Fun fact: just last month I threw together a little JavaScript simulator to illustrate how even with no population growth (a “replacement rate” of one child per adult) a population grows while its life expectancy grows, which some people find unintuitive.