Unless they happened to bump into each other at QParty, the first time Ruth and JTA met my school friend Gary was at my dad’s funeral. Gary had seen mention of the death in the local paper and came to the wake. About 30 seconds later, Gary and I were reminiscing, exchanging anecdotes about our misspent youths, when suddenly JTA blurted out: “Oh my God… you’re Sc… Sc-gary?”

Ever since then, my internal monologue has referred to Gary by the new nickname “Scgary”, but to understand why requires a little bit of history…

Despite having been close for over a decade, Gary and I drifted apart somewhat after I moved to Aberystwyth in 1999, especially as I became more and more deeply involved with volunteering at Aberystwyth Nightline and the resulting change in my social circle which soon was 90% comprised of fellow volunteers, (ultimately resulting in JTA’s “What, Everyone?” moment). We still kept in touch, but our once more-intense relationship – which started in a primary school playground! – was put on a backburner as we tackled the next big things in our lives.

Something I was always particularly interested both at Nightline and in the helplines I volunteered with subsequently was training. At Nightline, I proposed and pushed forward a reimplementation of their traditional training programme that put a far greater focus on experience and practical skills and less on topical presentations. My experience as a trainee and as a helpline volunteer had given me an appreciation of the fundamentals of listening and I wanted future trainees to be able to benefit from this by giving them less time talking about listening and more time practising listening.

The primary mechanism by which helplines facilitate such practical training is through roleplaying. A trainer will pretend to be a caller and will talk to a trainee, after which the pair (along with any other trainers or trainees who are observing) will debrief and talk about how it went. The only problem with switching wholesale to a roleplay/skills-driven approach to training at Aberystwyth Nightline, as I saw it, was the approach that was historically taken to the generation of roleplay material, which favoured the use of anonymised adaptations of real or imagined calls.

Roleplay scenarios must be realistic (so that they simulate the experience of genuine calls with sufficient accuracy that they are meaningful) but they must also be effective (at promoting the growth of the skills that are needed to best-support callers). Those two criteria often come into conflict in roleplay scenarios: a caller who sits in near-silence for 20 minutes may well be realistic, but there’s a limit to how much you can learn from sitting in silence; a roleplay which tests every facet of a trainee’s practical knowledge provides efficiency, but does not reflect the content of any call that has ever really happened.

I spent some time outlining the characteristics of best-practice roleplays and providing guidelines to help “train the trainers”. These included ideas, some of which were (then) a little radical, like:

- A roleplay should be based upon a character, not a story: if the trainer knows how the call is going to end, this constrains the opportunity for the trainee to explore the space and experiment with listening concepts. A roleplay is necessarily improvisational: get into your character, let go of your preconceptions.

- Avoid using emotionally-charged experiences from your own life: use your own experience, certainly, but put your own emotional baggage aside. Not only is it unfair to your trainee (they’re not your therapist!) but it can be a can of worms in its own right – I’ve seen a (great) trainee help a trainer to make a personal breakthrough for which they were perhaps not yet ready.

- Don’t be afraid to make mistakes: you’re not infallible, and you neither need to be nor to present yourself as a perfect example of a volunteer. Be willing to learn from the trainees (I’ve definitely made use of things I’ve learned from trainees in real calls I’ve taken at Samaritans) and create a space in which you can collectively discuss how roleplays went, rather than simply critiquing them.

In order to demonstrate the concepts I was promoting, I wrote and demonstrated a significant number of sample roleplay ideas, many of which I (or others) would then go on to flesh-out into full roleplays at training sessions. One of these for which I became well-known was entitled My Friend Scott.

The caller in this roleplay presents with suicidal ideation fuelled by feelings of guilt and loneliness following the accidental death, about six months prior, of his best friend Scott, for which he feels responsible. Scott had been the caller’s best friend since childhood, and he’s fixated on the adventures that they’d had together. He clearly has a huge admiration for his dead friend, bordering on infatuation, and blames himself not only for the death but for the resulting fracturing of their shared friendship group and his subsequent isolation.

(We’re close to getting back to the “Scgary story”, I promise. Hang in here.)

When I would perform this roleplay as the caller, I’d routinely flesh out Scott and the caller’s backstory with anecdotes from my own childhood and early-adulthood: it seemed important to be able to fill in these kinds of details in order to demonstrate how important Scott was to the caller’s life. Things that I really did with any of several of my childhood friends found their way, with or without embellishment, into the roleplay, like:

- Building a raft on the local duck pond and paddling out to an island, only to have the raft disintegrate and have to swim back

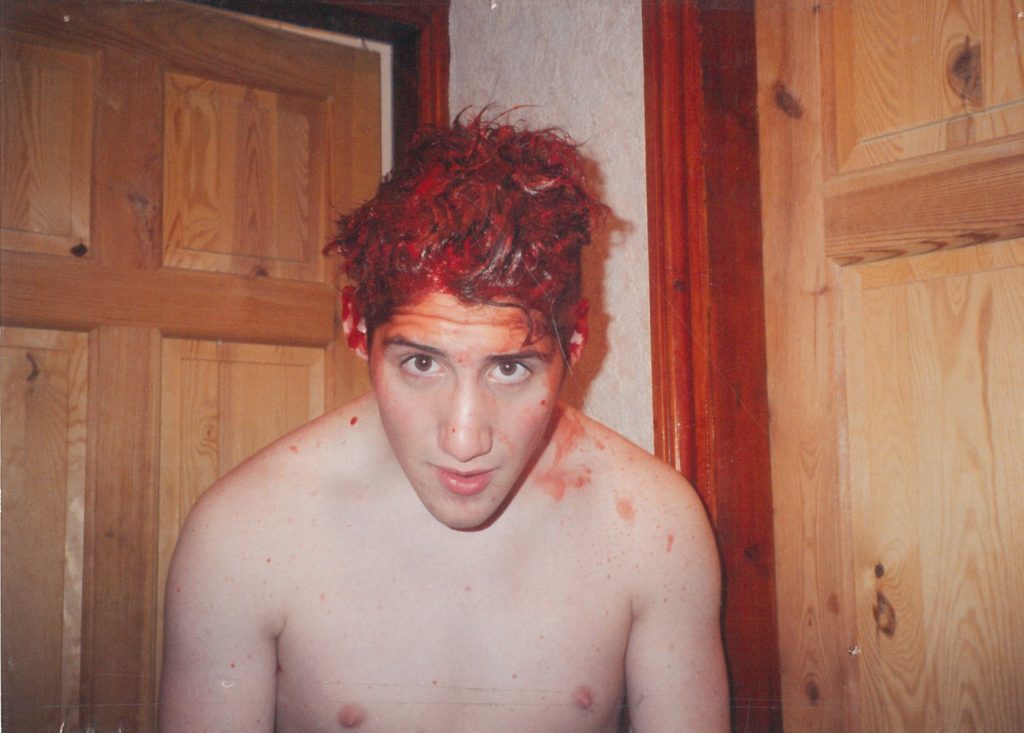

- An effort to dye a friend’s hair bright red which didn’t produce a terribly satisfactory result but did stain many parts of a bathroom

- Camping in the garden, dragging out a desktop computer and extension cable to fully replicate the “in the wild” experience

- Flooding my mother’s garden (which at that time was a long slope on clay soil) in order to make a muddy waterslide

- Generating fake credit card numbers to facilitate repeated month-long free trials of an ISP‘s services

- Riding on the bonnet of a friend’s first car, hanging on to the windscreen wipers, eventually (unsurprisingly) falling off and getting run over

Of course: none of the new Nightliners I trained knew which, if any, of these stories were real – that was never a part of the experience. But many were real, or had a morsel of truth. And a reasonable number of them – four of those in the list above – were things that Gary and I had done together in our youth.

JTA’s surprise came from that strange feeling that occurs when two very parts of your life that you thought were completely separate suddenly and unexpectedly collide with one another (I’m familiar with it). The anecdote that Gary had just shared about our teen years was one that exactly mirrored something he’d heard me say during the My Friend Scott roleplay, and it briefly crashed his brain. Suddenly, this was Scott standing in front of him, and he’d been able to get far enough through his sentence to begin saying that name (“Sc…”) before the crash stopped him in his tracks and he finished off with “…gary”.

I’m not sure whether or not Gary realises that, in my house at least, he’s to this day been called “Scgary”.

I bumped into him, completely by chance, while visiting my family in Preston this weekend. That reminded me that I’d long planned to tell this story: the story of Scgary, the imaginary person who exists only in the minds of the tiny intersection of people who’ve both (a) met my friend Gary and know about some of the crazy shit we got up to together when we were young and foolish and (b) trained as a volunteer at Aberystwyth Nightline during the window between me overhauling how training was provided and ceasing to be involved with the training programme (as far as I’m aware, nobody is performing My Friend Scott in my absence, but it’s possible…).

Gary asked me to give him a shout and meet up for a beer next time I’m in his neck of the woods, but it only occurred to me after I said goodbye that I’ve no idea what the best way to reach him is, these days. Like many children of the 80s, I’ve still got the landline phone numbers memorised of all of my childhood friends, but even if that number is still valid, it’d be his parents house!

I guess that I’ll let the Internet do the work for me: perhaps if I write this, here, he’ll find it, somehow. Hi, Scgary!