This is an alternate history of the Web. The premise is true, but the story diverges from our timeline and looks at an alternative “Web that might have been”.

Prehistory

This is the story of P3P, one of the greatest Web standards whose history has been forgotten1, and how the abject failure of its first versions paved the way for its bright future decades later. But I’m getting ahead of myself…

Drafted in 2002 in the wake of growing concern about the death of privacy on the Internet, P3P 1.0 aimed to make the collection of personally-identifiable data online transparent. Hurrah, right?

Not so much. Its immediate impact was lukewarm to negative: developers couldn’t understand why their cookies were no longer being accepted by Internet Explorer 6, the first browser to implement the standard, and the whole exercise was slated as providing a false sense of security, not stopping actual bad guys, and an attempt to apply a technical solution to a political problem.2

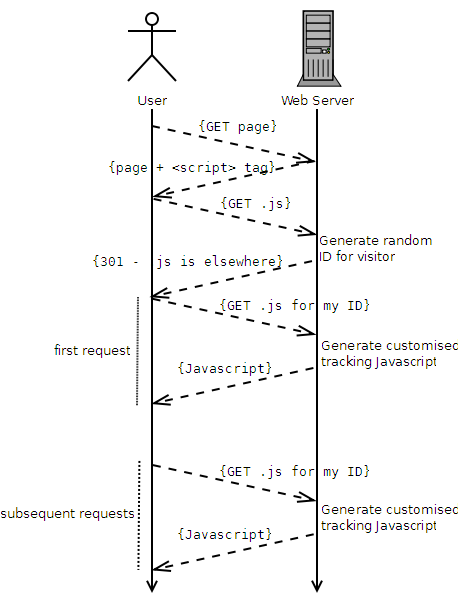

Developers are lazy3 and soon converged on the simplest possible solution: add a garbage HTTP header like P3P: CP="See our website for our privacy policy." and your cookies work just fine! Ignore the problem, ignore the

proposed solution, just do what gets the project shipped.

Without any meaningful enforcement it also perfectly feasible to, y’know, just lie about how well you treat user data. Seeing the way the wind was blowing, Mozilla dropped support for P3P, and Microsoft’s support – which had always been half-baked and lacked even the most basic user-facing controls or customisation options – languished in obscurity.

For a while, it seemed like P3P was dying. Maybe, in some alternate timeline, it did die: vanishing into nothing like VRML, WAP, and XBAP.

But fortunately for us, we don’t live in that timeline.

Revival

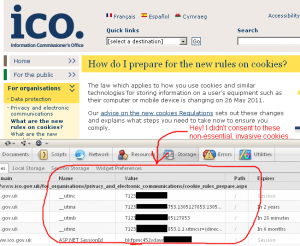

In 2009, the European Union revisited the Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive. The initial regulations, published in 2002, required that Web users be able to opt-out of tracking cookies, but the amendment required that sites ensure that users opted-in.

As-written, this confusing new regulation posed an immediate problem: if a user clicked the button to say “no, I don’t want cookies”, and you didn’t want to ask for their consent again on every page load… you had to give them a cookie (or use some other technique legally-indistinguishable from cookies). Now you’re stuck in an endless cookie-circle.4

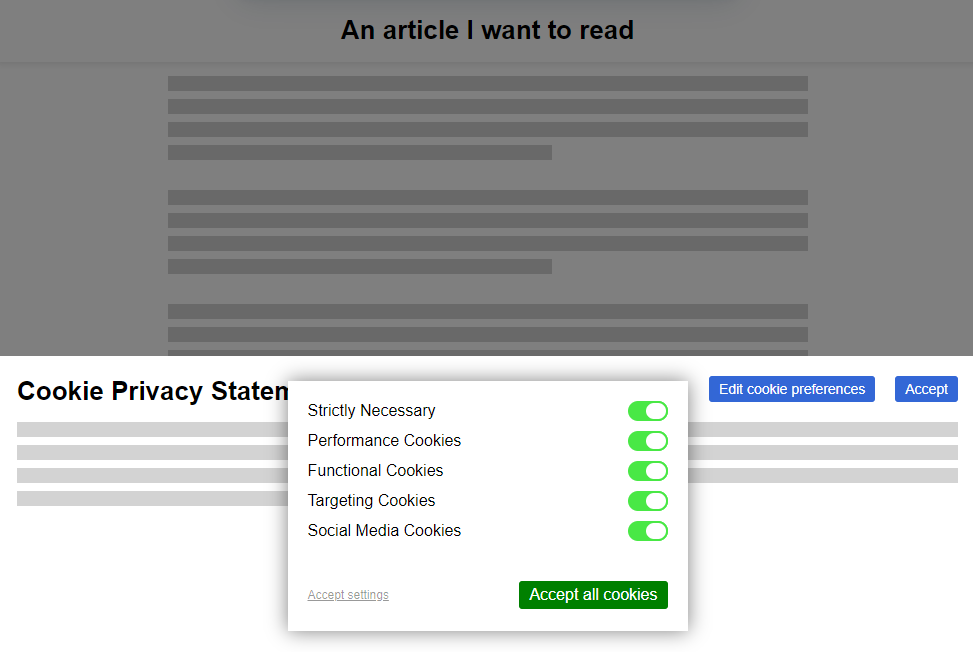

This, and other factors of informed consent, quickly introduced a new pattern among those websites that were fastest to react to the legislative change:

Web users rebelled. These ugly overlays felt like a regresssion to a time when popup ads and splash pages were commonplace. “If only,” people cried out, “There were a better way to do this!”

It was Professor Lorie Cranor, one of the original authors of the underloved P3P specification and a respected champion of usable privacy and security, whose rallying cry gave us hope. Her CNET article, “Why the EU Cookie Directive is a solved problem”5, inspired a new generation of development on what would become known as P3P 2.0.

While maintaining backwards compatibility, this new standard:

- deprecated those horrible XML documents in favour of HTTP

headers and

<link>tags alone, - removing support for

Set-Cookie2:headers, which nobody used anyway, and - added features by which the provenance and purpose of cookies could be stated in a way that dramatically simplified adoption in browsers

Internet Explorer at this point was still used by a majority of Web users. It still supported the older version of the standard, and – as perhaps the greatest gift that the much-maligned browser ever gave us – provided a reference implementation as well as a stepping-stone to wider adoption.

Opera, then Firefox, then “new kid” Chrome each adopted P3P 2.0; Microsoft finally got on board with IE 8 SP 1. Now the latest versions of all the mainstream browsers had a solid implementation6 well before the European data protection regulators began fining companies that misused tracking cookies.

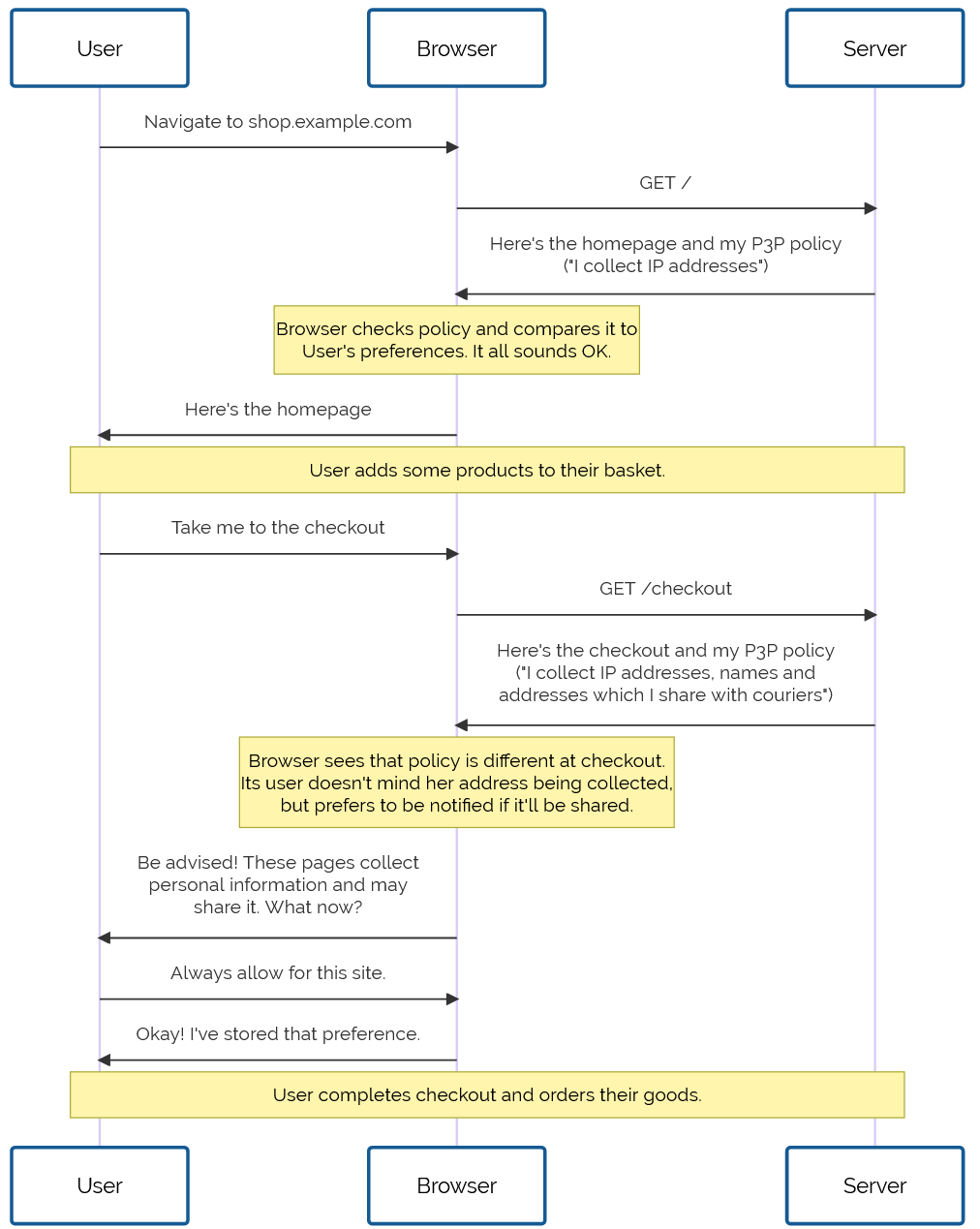

But where the story of P3P‘s successes shine brightest came in 2016, with the passing of the GDPR. The W3C realised that P3P could simplify both the expression and understanding of privacy policies for users, and formed a group to work on version 2.1. And that’s the version you use today.

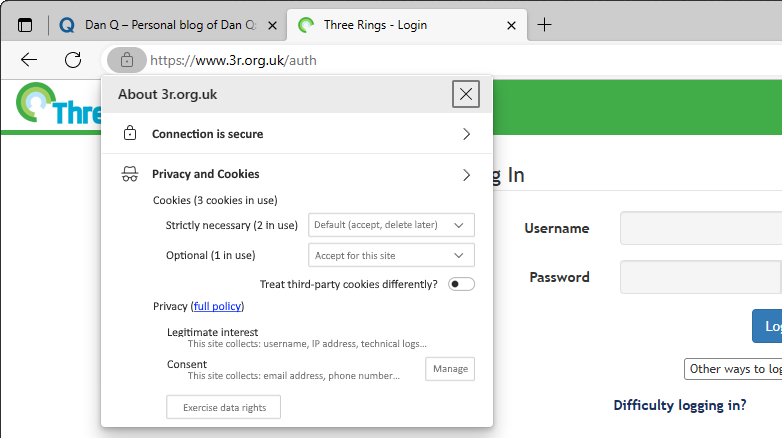

When you launch a new service, you probably use one of the many free wizard-driven tools to express your privacy policy and the bases for your data processing, and it spits out a

template privacy policy. You need the human-readable version, of course, since the 2020 German court ruling that you cannot rely on a machine-readable privacy policy alone, but

the real gem is the P3P: 2.1 header version.

Assuming you don’t have any unusual quirks in your data processing (ask your lawyer!), you can just paste the relevant code into your server configuration and you’re good to go. Site users get a warning if their personal data preferences conflict with your data policies, and can choose how to act: not using your service, choosing which of your features to opt-in or out- of, or – hopefully! – granting an exception to your site (possibly with caveats, such as sandboxing your cookies or clearing them immediately after closing the browser tab).

Sure, what we’ve got isn’t perfect. Sometimes companies outright lie about their use of information or use illicit methods to track user behaviour. There’ll always be bad guys out there. That’s what laws are there to deal with.

But what we’ve got today is so seamless, it’s hard to imagine a world in which we somehow all… collectively decided that the correct solution to the privacy problem might have been to throw endless popovers into users’ faces, bury consent-based choices under dark patterns, and make humans do the work that should from the outset have been done by machines. What a strange and terrible timeline that would have been.

Footnotes

1 If you know P3P‘s history, regardless of what timeline you’re in: congratulations! You win One Internet Point.

2 Techbros have been trying to solve political problems using technology since long before the word “techbro” was used in its current context. See also: (a) there aren’t enough mental health professionals, let’s make an AI app? (b) we don’t have enough ventilators for this pandemic, let’s 3D print air pumps? (c) banks keep failing, let’s make a cryptocurrency? (d) we need less carbon in the atmosphere or we’re going to go extinct, better hope direct carbon capture tech pans out eh? (e) we have any problem at all, lets somehow shoehorn blockchain into some far-fetched idea about how to solve it without me having to get out of my chair why not?

3 Note to self: find a citation for this when you can be bothered.

4 I can’t decide whether “endless cookie circle” is the name of the New Wave band I want to form, or a description of the way I want to eventually die. Perhaps both.

5 Link missing. Did I jump timelines?

6 Implementation details varied, but that’s part of the joy of the Web. Firefox favoured “conservative” defaults; Chrome and IE had “permissive” ones; and Opera provided an ultra-configrable matrix of options by which a user could specify exactly which kinds of cookies to accept, linked to which kinds of personal data, from which sites, all somehow backed by an extended regular expression parser that was only truly understood by three people, two of whom were Opera developers.